Women Aviators (25 page)

Authors: Karen Bush Gibson

Once again, they headed south along Central America. The first few days were met with route changes to avoid flying in bad weather. Even though they had crossed the Drake Passage before, Jennifer said she worried about the hostile body of water. They crossed it on December 30 and, for a change, had good weather awaiting themâfor a few days at least.

The winds were particularly fierce, and they found themselves grounded for several days. They stayed in tents and abandoned huts at the Carvajal base. They weren't very welcome, though; a group of elephant seals took a disliking to the Polar First team, snapping at them.

There wasn't much to do except wait for the weather to clear. Jennifer and Colin get along well, except when it comes to music. Jennifer enjoys listening to classical music; Colin prefers anything else.

After the weather cleared, they took off for the site of their previous helicopter crash. Although the wrecked machine had been hauled off to a landfill, Colin still had the key, and the two buried it there. Although visiting the crash site and saying goodbye was emotional, the experience gave them closure.

The trip across Antarctica was almost entirely dictated by the weather. A hint of blue in the sky would send the pilots scurrying to pack up. Even when visibility was good with clear skies, they had to deal with strong headwinds. The higher their altitude, the greater the winds. But if they flew too low, they burned more fuel. Still, they usually found an altitude that worked out.

They crossed the Drake Passage again; this stage was shorter than anticipated due to strong tailwinds that put them back in Chile. They had survived the South Pole. Now it was time for the North Pole.

They approached the Arctic region in April. Jennifer admitted to having nerves, though this was mainly due to fear of the unknown. But flying over the North Pole was also similar to navigating over Antarctica in that they were constantly looking for windows of good weather. They found them and were on their way.

The red Bell 407 helicopter made the around-the-world flight from pole to pole in 170 days, 22 hours, 47 minutes, and 17 seconds; they reached the place they started, Fort Worth, on May 24, 2007. The amazing sights included two of the coldest places on Earth, as well as some of the hottest too. They refueled 101 times in 26 countries for the 32,206-mile (51,819 kilometer) trip.

The helicopter used on the world trip made a final trip to the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. Jennifer has been awarded both a silver medal and the Britannia Trophy by the Royal Aero Club. She's also a two-time Guinness World Record holder.

A trip like this takes a huge amount of preparation. Fueling stations and airports aren't very plentiful at either polar region, so Jennifer and Colin had to have fuel stored in remote locations. Fortunately, the woman who set the Guinness World Record in 1997 for flying the globe in a helicopter knew how to plan ahead.

Jennifer was born in Providence, Rhode Island, in 1940. Although she may have been born in the United States, her heart belongs to Great Britain. Her British father and American mother returned to England when she was four years old. She went to school there and graduated with a degree in textile design. In between working as a textile designer, she married, raised three children, and traveled the globe. She had a nose for adventure, whether it was trekking in Nepal or running a marathon.

Flying, however, wasn't one of the adventures that she ever considered. In fact, she didn't think about flying until she was 54. Her husband bought half a share in a helicopter. Jennifer said he told her that she had better learn to fly it because he didn't have time. Despite being asked if she wanted the “wives” course, which was little more than a helicopter tour, Jennifer signed up for helicopter training at flight school, and she found that she rather enjoyed it.

Flying a helicopter isn't easier than piloting an airplane. The European flight schools that Jennifer looked at required anywhere from 45 to 60 hours of flight time, seven written exams, and a radio test. Even people who already hold airplane pilot licenses must fly an additional 39 hours in a helicopter before they can test for the license.

In 1994, Jennifer received her helicopter pilot's license. She heard that only three men had traveled around the world with

a helicopter, and they had used autopilot. Jennifer made the trip in 1997 with a copilot and became the first woman to circumnavigate the globe in a helicopter. At the same time, she raised $100,000 for Save the Children. This first trip was a latitudinal journey from east to west. She did it again in 2000 by herself and without autopilot. She was the first person, male or female, to take a piston-engine helicopter around the world.

Jennifer does more than set records. She also enters races, such as the London to Sydney Air Race of 2001 in which she placed third. She has also run races, such as the 250-kilometer (155 mile) race across the Namib Desert supporting the Scott Polar Research Institute, which she attempted at age 69.

Many of Jennifer's adventures, whether in a helicopter or on foot, benefit charities such as Operation Smile and SOS Children's Villages.

Now Solo: One Woman's Record-Breaking Flight Around the World

by Jennifer Murray (Mainstream Publishing, 2002)

Polar First website,

www.polarfirst.com

Polar First

by Jennifer Murray (PPP Company, 2008)

Teaching Children to Fly

I

MAGINE A GROUP OF CHILDREN,

both boys and girls, on an airfield, with lots of bright smiles and perhaps more than a few lips trembling with fear. Chances are, all eyes are big with wonder. They take trips to airports, visit aerospace museums, and learn how to do preflight checks. Many get to ride in a real airplane. Often it's the first airplane ride they have ever taken.

Welcome to an Ida Van Smith Flight Club gathering, where minority children can learn to fly.

Ida Van Smith opened her clubs because she wanted children to have opportunities that took her half a century to experience. She said, “I believe that anything children do very young, they will probably be able to learn better and feel more at ease with than if they wait and they were my age to begin.”

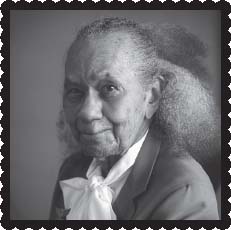

Learning to fly airplanes had been her dream since she saw her first one at the age of three. Being both African American and female meant that there was more standing in the way of that dream, but she never forgot it.

Finally, in 1967, 50-year-old grandmother and teacher Ida Van Smith took flying lessons. She had looked into classes at Butler Aviation School at LaGuardia Airport in New York, but she received too many stares. She decided to shop around and found an instructor she liked at Fayetteville's Grannis Field Airport in her home state of North Carolina.

After she earned her pilot's license and instructor rating, this history and special education teacher opened a flight club in Long Island, New York. With a grant from the FAA, she was able to get an aircraft simulator. She provided a Cessna 172. Ida was the first African American female flight instructor in New York and the first African American female pilot from North Carolina.

Once per month during the 1970s, Smith held workshops at York College in Jamaica, New York. She invited air-traffic controllers, commercial pilots, airplane mechanics, and other people in aviation to talk with students from the Ida Van Smith Flight Clubs.

Funding for the program often came from Ida's own pockets in the early days. But word of Ida's schools caught on and spread. More than 20 schools opened in locations in New York, North Carolina, Texas, and St. Lucia in the Caribbean. Thousands of young people from ages 3 to 19 have experienced aviation through the Ida Van Smith Flight Clubs, and many have gone on to aviation careers with airlines or in the military.

Born in Lumberton, North Carolina, in 1917, Ida remembered her father taking her to see a barnstorming exhibition at the airport when she was three or four years old. It was an image that stayed with her. She was fascinated by aviation, but it would be almost 50 years before she became a licensed pilot. She founded the Ida Van Smith Flight Clubs in 1967, introducing children and young adults to the careers that aviation and space had to offer.

Ida moved to New York City after graduating from Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina, in the 1940s. She earned her master's degree at Queens College in New York City and began teaching in New York City's schools. Ida also hosted a cable-television show on aviation and taught introductory aviation at York College of the City University of New York. She wrote articles for aviation and education journals in addition to a newspaper column titled, “Come Fly with Me.” She was honored many times for her contributions to education and aviation, including becoming the first African American woman inducted into the International Forest of Friendship in Atchison, Kansas.

With her belief that you're never too young to learn about aviation, Ida also created the

Fly with Me Coloring Book.

The 32-page coloring book has a story about flying within its pages.

Retiring from teaching in 1977, Ida remained active with her flight schools and the flying groups she was a member ofâNinety-Nines, Black Wings, and Negro Airmen Internationalâuntil her death in 2003. The Ida Van Smith Flight Clubs (sometimes known as the Ida Van Smith-Dunn flight clubs) have earned many honors for their work with youth.

The Ida Van Smith Flight Clubs aren't the only clubs dedicated to introducing aviation to children. The Royal Air Force of Great Britain sponsors the Air Cadets Organisation for young people between 13 and 20 years of age. Not only are students introduced to aviation, but the Air Cadets program also provides training.

The program actually has a long history, starting in 1859, girls were not allowed to join until the early 1980s. A similar program operates in Canada: the Royal Canadian Air Cadets. Operating in other places throughout the world are the Experimental Aircraft Association Young Eagles programs for 8- to 17-year-olds. The program starts with a free flight and then offers different steps for young people interested in aviation. Smaller programs are offered in various communities. For instance, the Bronze Eagles Flying Club was started about 45 years ago by African American pilots in Houston but has spread throughout Texas and Arkansas. The club's goal is to expose African American youth to the possibilities of aviation through an annual fly-in event and a two-week Summer Flight Academy. The Summer Flight Academy teaches 16 high school students how to fly. Some of the participants, such as Decarla Greaves, have gone on to careers in aviation.