Women Aviators (4 page)

Authors: Karen Bush Gibson

With her dark hair and engaging personality, Harriet considered being an actress. She spent a little time on the stage in San Francisco before turning to writing. She wrote feature articles for publications such as the

San Francisco Bulletin

.

After some success, she moved across the country to New York City.

Succeeding as a journalist, particularly as a female journalist in New York City in 1903, was almost impossible. But Harriet brought strong writing skills, intelligence, and determination

with her. After showing her published work, which included theatrical reviews and articles about life in Chinatown, she convinced the editors of

Leslie's Illustrated Weekly

to try her as a contributing writer.

Harriet's first article for the popular newspaper was titled “Curious Chinese Customs.” She wrote drama critiques, household tips, and political articles. She profiled everyone from actresses to acrobats. As a friend of noted filmmaker D. W. Griffith, she wrote screenplays as well, seven of which were turned into movies.

Traveling as a photojournalist to Egypt, Mexico, Cuba, Europe, and Iceland broadened Harriet's world even more.

Leslie's Illustrated Weekly

hired Harriet as a staff writer, and she wrote more than 250 articles for the paper during her career. Her talent and success led to assignments full of the excitement she craved. On a visit to the Vanderbilt racetrack, Harriet was taken for a ride at 100 miles per hour in a 120-horsepower Vanderbilt Cup Racer. She bought her own car, which she learned to drive and repair herself.

Speed gave Harriet a thrill, and a few years later she attended the International Aviation Tournament in Belmont Park, New York, to see what airplanes had to offer. She watched one pilot, John Moisant, wreck his plane before getting off the ground. Moisant immediately bought a monoplane from another pilot and won the race. Harriet introduced herself to John, who, with his brother Alfred, ran an aviation school in Long Island, New York. She also met Matilde Moisant, their sister. Harriet and Matilde hit it off and became close friends.

Two months later, John Moisant died at an aviation exhibition in New Orleans when his plane went into a dive. Accidents were common in early aviation, with more than a hundred deaths from aviation by the spring of 1911. But Harriet didn't

let that stop her. In May 1911, Harriet and Matilde began classes at the Moisant Aviation School. Most flight schools, including the Wright Brothers Flying School, refused to accept women as students. As soon as the papers learned that two women were learning to fly, it became big news. Harriet focused her writing on aviation and convinced

Leslie's

to let her do a series. Audiences loved her feature articles about learning to fly. In “How a Woman Learns to Fly,” Harriet wrote, “It feels like riding in a high powered automobile, minus bumping over the rough roads, continually signaling to clear the way and keeping a watchful eye on the speedometer to see that you do not exceed the limit and provoke the wrath of the bicycle policeman.”

On August 1, 1911, Harriet became the first woman in the United States to earn a pilot's license. When her FAI license arrived, she saw that she was Pilot Number 37. A few weeks later, Matilde became the second US woman to earn a license. They were among about ten women in the world who were licensed to fly an airplane.

After getting her license, Harriet designed her own flight suit, what she called a knickerbocker uniform. A month later, she became the first woman to fly at night when she flew over Staten Island, New York. Air exhibitions were very popular, and everyone wanted to see the woman pilot they had read about in

Leslie's.

Harriet flew at meets throughout the United States and Mexico. While she was in Mexico, an idea began to form in her mind.

Since Louis Blériot had first crossed the English Channel in 1909, a few other pilots had followed, including John Moisant. Even more had failed at it. One woman had flown over the English Channel as a passenger, but no woman had flown solo over the channel. Harriet decided she wanted to be first.

The second American woman to earn her pilot's license, Matilde Moisant, received hers sixteen days after her friend Harriet Quimby. Together the two women participated in exhibition flights as part of a group of performing pilots called the Moisant International Aviators.

Matilde's first exhibition came about a month after receiving her license. She won a trophy for flying at an altitude of 1,200 feet (366 meters) at the Nassau Boulevard Aviation Meet, beating Harriet. High-altitude flying seemed to be Matilde's specialty, as she demonstrated at meets for the next seven months.

Her family, still grieving over the death of her brother John in an aviation accident, begged her to quit flying. Matilde finally gave in, saying she would quit after one more exhibition flight in Wichita Falls, Texas, on April 14, 1912. As she started to land, her airplane burst into flames because of a fuel-tank leak. The plane crashed. Matilde was pulled out with her clothing on fire, but her heavy wool flying suit saved her from serious burns.

That flight was Matilde's last. Two and a half months later, her good friend Harriet Quimby died when her plane crashed.

She traveled to England on an ocean liner. Unlike Blériot, who flew from France to England, she would fly from England to France. She kept quiet about her plans because she didn't want another woman to beat her. The people who knew about her quest tried to talk her out of it; this group included Gustav Hamel, an aviator who offered to pretend to be her by wearing

the purple flight suit. She refused but agreed to use a compass for the trip.

Harriet's nighttime flight had been big news, but that wouldn't be the case for the bigger challenge of crossing the English Channel. The

Titanic,

a passenger ship that had left England via the English Channel, hit an iceberg in the Atlantic Ocean and sank. Thus, few noticed the stories about the first woman's solo flight over the 22-mile stretch of water separating Great Britain from the European mainland. The news of the

Titantic

disaster overshadowed everything else.

Three months later, Harriet arrived at the third annual Boston Aero Meet, an event that promised the highest fee yet. When she met with the organizer, William Willard, and his son, the two men tossed a coin to see who would have the honor of a flight with Harriet. The elder Willard won the toss. Harriet took off in her new 70-horsepower, two-seater Blériot plane and took her passenger around the lighthouse. Five thousand people watched the plane approach over Dorchester Bay before it suddenly went into a nosedive. Willard fell out of the plane to his death. Harriet looked like she might regain control of the airplane, but she too fell into the shallow waters of Dorchester Bay and died instantly.

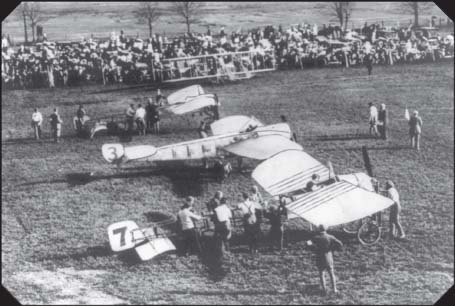

Boston Aero Meet, 1910.

Library of Congress

Harriet Quimby was a woman who inspired others. One of those she inspired was Amelia Earhart, who had this to say about Harriet: “To cross the Channel in 1912 required more bravery and skill than to cross the Atlantic todayâ¦. We must remember that, in thinking of America's first great woman flier's accomplishment.”

What exactly happened continues to be a mystery to this day, although there are theories. Willard, a heavy man, might have stood up or leaned forward, throwing the balance of the airplane off. (There were no seatbelts in Harriet's plane.) A meet official mentioned another possibility: that the plane's cables were caught in the steering.

Harriet Quimby was only 37 years old when she died, but she had achieved so much in her life. In a time when women had few rightsâthey weren't even allowed to voteâHarriet had two successful careers and supported herself. The first American woman pilot and the first woman to cross the English Channel was truly an aviation pioneer, so in 1991, eighty years after receiving her license, the US government honored her with a stamp in the Pioneers of Aviation series. The 50-cent US airmail

stamp depicts a beautiful woman, adorned in purple, smiling as a Blériot monoplane flies in the background.

“Harriet Quimby” in

Chasing the Sun,

PBS,

www.pbs.org/kcet/chasingthesun/innovators/hquimby.html

Harriet Quimby: America's First Lady of the Air

(Aviation History Series) by Anita P. Davis and Ed Y. Hall (Honoribus Press, 1993)

“Harriet Quimby” on Women in Aviation and Space History website, Smithsonian Air and Space Museum,

http://airandspace.si.edu/explore-and-learn/topics/women/Quimby.cfm

Queen Bess

B

ESSIE

C

OLEMAN KNEW WHAT

she wanted: she wanted to learn how to fly an airplane. How hard could it be? She was a successful 27-year-old woman in Chicago who had pulled herself, mother, and three younger sisters out of poverty. Knocking on the doors of flight schools, the attractive woman with copper skin asked what it would cost to take flying lessons. Everyone turned her down as a student. Some refused her because she was a woman, others because she was African American. Most flight schools refused her for both reasons. So Bessie saved up money by opening up a chili parlor and, in her spare time, learned to speak French. Her friend,

Chicago Defender

editor Robert Abbott, had told her that the French were more accepting of race and gender.

In November 1920, Bessie sailed to France for a 10-month course at the famed Caudron Brothers' School of Aviation at Le Crotoy, France. Bessie walked the nine miles to the airfield every day for flight lessons in order to save her limited funds. She finished the course in seven months, learning to fly a 27-foot (8.2 meters) biplane with a 40-foot (12 meters) wingspan. It was the French Nieuport Type 82.

On June 15, 1921, Bessie took her test. She flew a five-kilometer course at an altitude of 50 meters (160 feet). She was also required to complete a figure eight and land within 50 meters of a designated spot. She received her license from the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale, becoming the first African American with a pilot's license. She was also the only woman among the 62 candidates who earned licenses during the six-month period.