Yoga for a Healthy Lower Back (25 page)

Read Yoga for a Healthy Lower Back Online

Authors: Liz Owen

Close your eyes and visualize your pristine lumbar region, the area of your back between your hips and the bottom of your back ribs. The muscles on either side of your spine are long, smooth, and gently curved inward toward the front body. They are evenly developed; the right and left sides are balanced. There is a slight indentation between the spinal muscles that forms a “valley” where the spinous processesâthe knobby, bony protuberances that extend backward from each vertebraâare just visible. Imagine touching your lumbar muscles and feeling how pliable they are, how they yield to your touch, and how they return to their original shape when you take your fingers away.

Wait . . . is this not your experience with your lumbar?

In reality, the lumbar muscles can be visiblyâand painfullyâimbalanced, with one side thicker and wider than the other, or, in the case of a hip imbalance or variations in leg length, one side longer or shorter than the other. The muscles can be curved and wavy, as in the case with a scoliosis. Sometimes there's no “valley” between the muscles at all, and the spinous processes press too far outward, forming a line of foothills climbing uncomfortably up the back. In other bodies, the valley is so deep, the lumbar muscles so overly thick and stiff, that one can barely see the skin, much less a hint of a spinous process. Some lumbar spines have a reverse, convex curvature. If your back is strongly imbalanced and you come into a standing forward bend, your lower back can look like a buckled and collapsed road after an earthquake, not a smooth, rolling highway on a clear day. I have seen all these conditions in my students' lumbar areas.

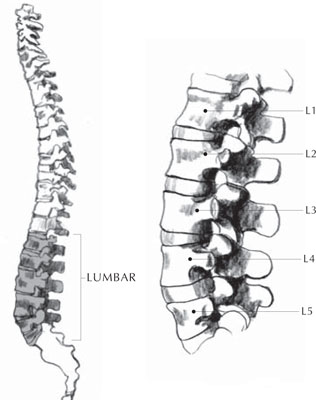

Looking through the lens of Western medicine, let's start with bones, muscles, and ligaments. Your lumbar spine (

illustration 13

) is composed of five bones, the L1-to-L5 vertebrae, which sit between your middle and upper backâcalled the thoracic spineâand your sacral spine. The lowest lumbar vertebra, L5, sits in between your back hip bones, where it connects with S1, the top sacral vertebra.

The joint between L5 and S1 allows for the rotation of your hips when you walk and run. This joint, along with the one above it, between lumbar vertebrae L4 and L5, are the most weight-bearing joints of the lower back. Consequently, they are the most prone to stresses that cause injury. More on the challenges associated with L5/S1 in a moment.

Unlike its neighbors, the sacral spine and the thoracic spine, your lumbar spine is a flexible stack of bones. Remember that your sacral bone is grounded into your back hip bones, so its range of motion is limited. Your thoracic spine is connected, by your ribs, to your breastbone, so it too is relatively limited in its options for movement. By contrast, there are no bony structures in your lumbar region to limit its movement in healthy, supporting ways, except at the very bottom, where L5 resides between your back hip bones.

Illustration 13. Your Lumbar Spine

Sit in a chair for a moment and see if you can feel what I mean. Move your shoulders and upper chest around, feeling movement throughout your shoulder girdle and chest. Feel how your whole upper chest, back, and shoulders are connected and moving together, unified by the musculature and bones that surround the area.

Now move your hips around on the seat of the chair, feeling how your sacral bone and hip bones are connected to one another and move as a unit, again stabilized by the musculature and ligaments around them.

Moving both your hips and your upper chest, now feel your lower back and visualize your lumbar spine. Feel how much movement there is in your lumbar region and around your waistline. Unless your back is extremely tight, you are probably feeling a lot of movement!

When I experience the movement of my lower back this way, I visualize that I'm holding a pearl necklace vertically with one hand holding each end. The pearls dangle and move as I move my hands, staying connected by the strong but supple threads that link them. Like this imaginary pearl necklace, the lumbar vertebrae are connected to each other by ligaments, the spongy intervertebral disks (commonly simply called “disks”), and the spinal muscles, which give it tremendous strength and allow for increased mobility, but there's not a lot else there to restrict its movement. It's as if your lumbar spine could do a dance all its ownâswaying, bending, and twisting, unfettered and fluid. To offer a second image, you can note that the spinal nerve roots that travel through the lumbar and sacral spine, branching out into the lower body, have the Latin name

cauda equina,

because of their resemblance to a horse's flowing tail.

The chain of pearls and the horse's tail are beautiful, graceful images for unencumbered, fluid movement and spaciousness in your lower back and abdomen, but you'll only experience them if your lumbar and abdominal core muscles are strong and the myofascia is flexible, working together to support your lumbar spine while it moves around. It's the job of the musculature to help the bony structures of your entire body move in a coordinated and healthy way, and that may be even more important in your lumbar region because of its independent nature. If the lumbar muscles are imbalanced, if your hip bones are tilted, if you have different leg lengths, or if some muscles are strong and others are weak, the vertebrae of your lumbar spine can get pushed and pulled around until injury happens to the lumbar ligaments, muscles, or the spinal disks themselves. The vertebrae can shift out of alignment with one another, putting pressure on the disks and the nerves that run through the spinal column to the abdominal organs, hips, and lower legs.

The fact is, lower back injuries and conditions are almost as common in our culture as the common cold. According to the National Institutes of Health, they are second only to the cold as a reason for a visit to the doctor.

2

But I would argue that “lower back pain” is too general a term. The types and intensity of lower back injuries and conditions are numerous and include arthritis, ligament and muscular strain and tears, a narrowing of the spinal canal (spinal stenosis), degenerative disk disease, spinal curvature (scoliosis), nerve root compression, slippage of one vertebra forward of the one beneath it (spondylolisthesis), herniation and rupture of the spongy disks between vertebrae, and an inflammatory arthritic condition that mainly affects the joints between spinal vertebrae (ankylosing spondylitis).

The therapeutic use of yoga for these conditions varies greatly from condition to condition. I do want to mention again that if you have had persistent pain for over two weeks and/or numbness, tingling, or weakness in your hips or legs, a diagnosis by a medical professional is of the utmost importance prior to beginning a yoga practice.

The Lower Lumbar Challenge: L4, L5, and S1

As we explore the lower back, it's important to understand that the most vulnerable part of the area, and the most common place of injury, is where your lumbar spine meets your sacral spine.

There are two main reasons why. First, as I mentioned earlier, the joint between the top of your sacral spine at S1 and the base of your lumbar spine at L5 is extremely importantâand equally vulnerable. For one thing, it is the lowest joint in the spine that includes a spinal disk, since the sacral vertebrae below it are fused together. When the lumbar spine bends forward, backward, or to the side, or when it rotates in a twist, the sacral spine stays in position with minimal movement. You can imagine the stress this can place on the disk between S1 and L5.

Second, you'll remember that lumbar vertebra L5 sits nestled below the top of your back hip bones in your sacrum, while L4 sits just above those bones. L5 doesn't move that much, because it is connected to the back hip bones by the iliolumbar ligament, which stabilizes the pelvis when you bend to the side. Sometimes this ligament extends up to lumbar vertebra L4, but in most bodies it does not. You're probably already imagining why the joint between L5 and L4 is so prone to injury: L5, wedged snugly inside the pelvic girdle, doesn't have as much movement as L4. So if you overwork your back in a side-bending, lifting, or twisting action, L4 moves and L5 doesn't necessarily move along with it. This creates stress and strain in the ligaments around those vertebrae, leaving the disk between them particularly vulnerable to injury. Snow shoveling, anyone? Gardening? Your lower back might be aching just thinking about it.

For these two reasons and others, injuries to the disks in the lower back are quite common. A disk becomes “herniated” when all or part of the spongy cushion inside it is forced through a part of the disk that is weak, either due to repetitive or sudden, jolting movements that cause stress and strain.

3

A herniated disk can eventually rupture, releasing spinal fluid and causing severe pain.

I talked a little about sciatic nerve pain and piriformis syndrome in chapter 2. Thinking about how common the diagnosis of “sciatica” is, it's probably not a big surprise to learn that the nerve fibers that bundle together to form your sciatic nerve come out of the area of your spine between lumbar vertebra L4 and sacral vertebra S3, right at the intersection of your lumbar and sacral spines, where the lumbar spine is most vulnerable to injury.

4

A diagnosis of sciatica or “radiculopathy” may also be given in the case of pain that radiates from the lumbar region through the hip and down the leg along the path of a spinal nerve root. These conditions can be caused by compression, inflammation, or injury to a spinal nerve root arising from a number of conditions, including a herniated disk, spinal stenosis, degenerative disk disease, and spondylolisthesis.

5

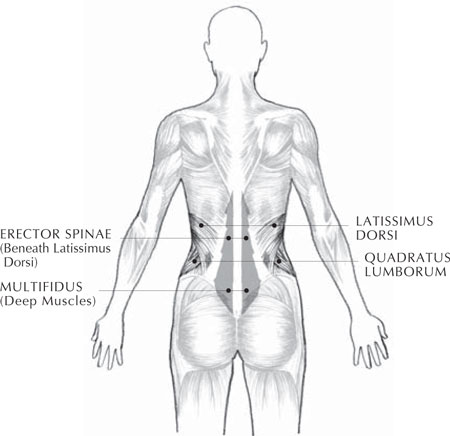

In case you haven't had enough anatomy yet, here's a quick sketch of the major lower back muscles (

illustration 14

), all of which will figure into the yoga practice in this chapter:

Illustration 14. The Muscles of the Lower Back

â¢Â Â

The latissimus dorsi muscles,

the big, broad outermost muscles that wrap around from the thoracic and lumbar spines to the side chest and the upper arm. Although this muscle group's main role is to move the shoulder joint, it also participates in the extension and lateral flexion of the lumbar spine.

â¢Â Â

The erector spinae group,

which bends your spine backward (extension), contributes to side bending (lateral flexion), and supports your spine in the upright position.

â¢Â Â

The transversospinalis group,

especially the multifidus muscles. These short, often overlooked major postural muscles help your lumbar spine extend and twist. They are what connect vertebra to vertebra all the way up your spine, and they remain in contraction for long periods of time while the spine is moving, standing, and sitting. Weakness in the multifidus muscles is common to many types of lower back pain.

â¢Â Â

The quadratus lumborum muscles,

which connect the lumbar spine from L1 through L4 to the back hip bones on either side of the spine and allow the lumbar spine to bend sideways and backward. Spasms of the quadratus lumborum muscles are a common source of lower back pain.

The tone of your hamstring muscles, which you felt when you experimented with a simple

forward-bending exercise

, also has a major effect on the health of your lumbar region; if your hamstrings are tight, they can tug on the hip bones, which in turn pull on the muscles of your lower back, potentially flattening the natural inward (lordotic) curve of your lumbar spine and creating stress and misalignments in your lower back.

Your psoas muscles are also important players in the game of lower back health because those muscles are involved in both forward bending (flexion) and the rotation of your trunk. If one or both of your psoas muscles are tight, they can pull your lumbar spine forward and down toward your lower abdomen. The lower back muscles then become contracted; the result is an uncomfortable exaggeration of the natural curve of the lumbar spine called

lordosis.

In this extreme position, the lower back can take on a form diagnosed as “swayback posture.”

6