You Majored in What? (14 page)

Read You Majored in What? Online

Authors: Katharine Brooks

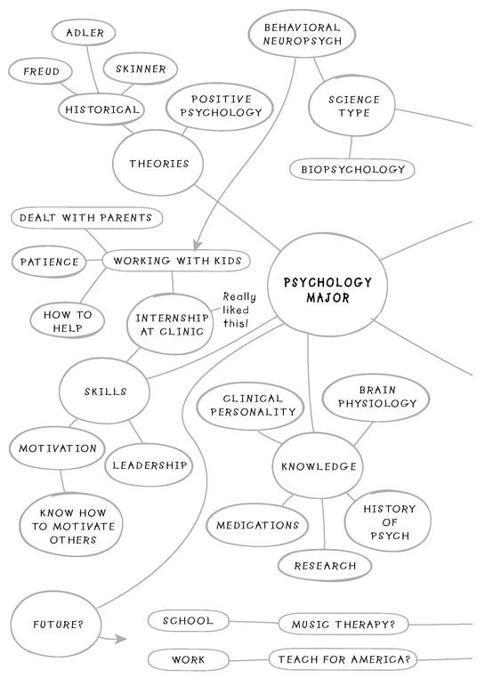

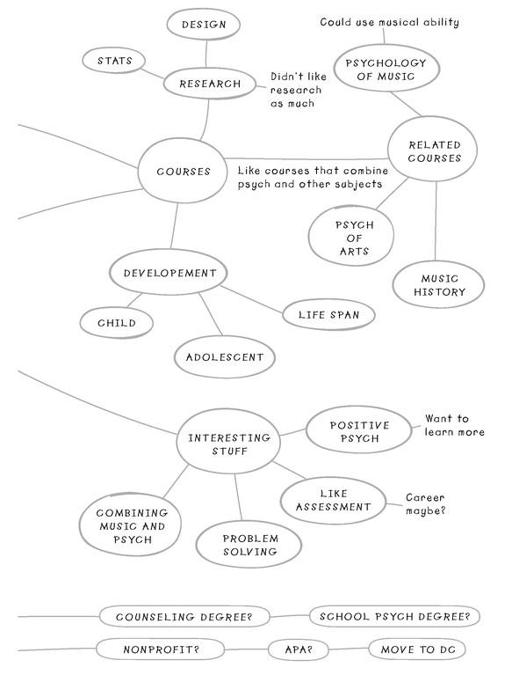

A sample Major Map for a psychology major can be found on pages 94-95.

After doing several Major Maps, students have made some interesting observations:

• History majors found that a key element for them was a never-ending search for “the truth.” They found it was also imperative to be keenly curious about everything. They could spend hours of intense focus on one project if necessary.

• English majors found that their major was extremely relevant and valuable to both work and life. They noted that to be a good English major you needed to be both classical and progressive. You needed to know where writing had been (that there is much to learn from the classics) and where writing is going (blogs, for example). They would be especially good in a multicultural workplace where appreciating and understand different cultures is imperative.

• Economics majors noted its far-reaching stance in business, politics, and solving social problems. They discovered that economics majors needed to embrace complexity, be very good at math, and be strong problem solvers. They also had to digest large amounts of information and distill it to the main points.

SELLING YOUR MAJOR TO YOUR FUTURE EMPLOYER

Now that you’ve analyzed your major and perhaps discovered new sources of knowledge and power in your experience, when the time comes you’ll need to be able to communicate it to your future employers, whoever they may be. It will be important to put yourself in the mind of an employer—will the employer know as much about your major as you do? Not likely. The worst assumption you can make is that your interviewer already knows everything about your major. In fact, it’s possible that not only is your interviewer not familiar with your major, but he or she may even harbor some negative or inaccurate views of it. So you need to become a star salesperson for your major and college degree.

A key piece of information you’ll need to learn is your interviewer’s college major. It’s easy enough to discover: when you are about to say something about your major, simply ask, “By the way, what was your major?” and respond positively regardless of the response. Once you know the interviewer’s major, you can adjust your approach in the interview. For example, if the recruiter understands your major (that is, she majored in it herself or hires a lot of people with your major), then emphasize what was special about what

you

studied or learned. What made you a better major than others who took the same subject?

On the other hand, if your interviewer majored in a subject other than yours, or doesn’t usually hire individuals with your major, then you need to educate him or her on the value of your major. For example, some schools offer a geography major. For those who aren’t familiar with the college-level study of geography, their last memory might be a geography class in grade school where they had to memorize all the states in alphabetical order. So their opinion may not be too high of a geography major. They may not know that a geography major has taken a very interdisciplinary course of study with roots in sciences and the social sciences, and usually has strong skills related to GPS tracking systems or would be a great urban planner. Or take a cognitive science major, a relatively new major. Many interviewers assume that it’s the same as a psychology major. If you’re a cognitive science major, then you know that’s not a correct analysis, so be prepared to explain the key elements of your major

and

how they are valuable to the job you’re applying for.

Even majors that are commonly known, such as English and history, are still going to require explanation to an employer who only took the one required English or history class in his or her academic career. In fact, he or she may have hated the course, so you’re going to have to present what you found valuable about it.

Below are some steps you can take to prepare for questions about your major:

1. To better sell your major to your future interviewer,

what knowledge, mindsets, or approach would someone with your major bring to a workplace?

Don’t worry if you don’t know the kind of job you’re applying these skills to yet; for the moment you can answer generically.

2.

Create stories related to your major and classes.

Can you take advantage of your classroom experiences to create stories that will show your knowledge, ability to learn, mindsets, or other important factors? Try using what you learned in your classes (the actual subjects, the metalearning, the mindsets, or character traits such as perseverance) by answering these typical interview questions:

Why did you choose your major? It doesn’t really relate to this job.

Why didn’t you major in _ if you were going to apply for this job in

_

?

What skills beyond the traditional writing, research, and/or communication skills have you acquired as a function of your major?

WISDOM BUILDERS: TEN ACADEMIC TRICKS AND TIPS TO IMPROVE YOUR GRADES AND LEARNING

1. ASK YOURSELF SOME KEY QUESTIONS

• When have you been at your best as a student?

• How did you know you were at your best?

• What did you do and what was the outcome?

• How did you feel?

• Can you reproduce that behavior and the feelings?

• What would you like to do more as a student?

• What could you really excel at if you tried your best?

2. SHOW UP

Did you know that study after study confirms that classroom presence is the single most important factor in the grade you receive? And not only that, but because the most important parts of the class are the beginning and the end, it’s important that you show up on time and not leave early.

And if you need another reason to show up, remember that you’re paying good money to take each class. Consider your tuition the admission price for each lecture. Although your tuition dollars pay for much more than the hours in the classroom, let’s focus on just the classroom for the moment. If a semester’s tuition is $10,000 and you’re taking four classes (a total of 180 hours of classroom time), you are paying approximately $55 for each class. That’s a concert ticket or a seat at a sports event. So sit up because you actually paid for this lecture.

Here are some tips for getting the most out of your class time:

• Sit toward the front of the room. The better students do sit in the front, if only because sitting in the front forces you to pay attention and the professor is more likely to see you.

You Majored in

What?

• Sit up. Don’t slouch or look casual.

• Use your computer for taking notes only—professors can tell when you’re emailing or instant-messaging.

• Look attentive and keep your eyes on the professor when you’re not taking notes.

• Don’t fall asleep. (A basic, yes, but you’d be surprised. . . .)

3. BE IN THE MOMENT

Remember in elementary school when your teacher would point at you and say “Pay attention!” What motivated her comment? What were you or your classmates doing that caused her to notice you? Let me ask you a question: Are you paying attention? Or is your behavior the same now?

You can take an active role even in a lecture-based class where you’re basically expected just to sit and listen. Look around. Watch how everyone else sits. Are your fellow students taking notes or are they checking e-mail? Are they actively listening or does it look as if their thoughts are a million miles away?

Ask yourself questions throughout the lecture: Do I get this? Does it make sense? Can I put myself in the mind of the individual being described? For instance, if your history professor is talking about Lincoln’s presidency, can you try to put yourself in the mindset of Lincoln? What was he feeling/thinking?

Notice and keep track of the skills you’re developing in your classes. Are you learning to work on a team, writing more efficiently, or managing your time better?

And when it comes to reading your assignments, don’t just passively read your textbook, looking to see when you can quit. Develop a relationship with what you’re reading. Why are you reading the assignment? What are you learning from it? Does the knowledge you’re gaining primarily comprise details and facts or concepts and ideas? Most textbooks help you find the important information by highlighting important material. Try to think beyond the text: Is what you’re reading related to what you’re learning in another class? And of course, how might you apply this to the workplace? How can you make an employer care that you’re learning this?

4. FIND A RATIONALE FOR EVERY CLASS YOU TAKE

Unfortunately, you don’t always get to pick your classes. Your curriculum has been designed to provide you with a depth and breadth of knowledge and experiences, which you may not be appreciating, particularly when you’re sitting in a boring class you don’t like. How many times have you said, “I’m just taking this because it’s required”? Or “I don’t really want to take this class; it just fit into the time slot I had available.” It’s time to change that attitude. Here are some strategies:

• Think about the Big Picture. Just because you don’t think you need this class right now, are there ways it might help you in the future?

• Try not to take any classes just because they make your life convenient, that is, because they fit neatly into your schedule. Start by identifying the classes that are most important to you and fit your schedule to accommodate them.

• Try creating metaphors for classes you don’t like. Chances are you’ve already come up with some choice adjectives to describe these classes: useless, boring, awful, wasteland, and so on. So could changing your metaphor change the way you approach the class? What if you called it a challenge you are determined to conquer? What if you referred to it as a game? Every game has a winner and the winner gets a prize. How will you define winning this game? Is it a particular grade? Surviving the class? Showing up every day? Completing all the assignments on time? Learning something in spite of the professor? And what is the prize you will give yourself for winning?

• Start developing your interview story about this class. Make it a lesson in survival—maybe even prevailing by getting an A despite the challenges.

• Try linking the class with something you enjoy doing, such as reading your assignments at your favorite coffeehouse. Or alternate your time preparing for the class with something you like to do, like watching a TV show or spending a few minutes on the computer. Just don’t get so caught up in your fun activity that you don’t get back to the assignment.

• Talk to students who are majoring in the topic you don’t like. Find out what they like about it and get tips for succeeding in it. Maybe you’ll pick up some of their enthusiasm.

• Could you consider the class a version of MySpace and see how many friends you can develop? Look around your classroom—any interesting people you’d like to meet? Maybe you could make it a goal to strike up a conversation after class with at least one different person each week—if nothing else, you could compare notes on how bad the class is. Or maybe they’ll have a different perspective you could learn.

• Consider the results of an alumni survey conducted a few years ago. Alumni were asked to name their favorite “useless” course, that is, the course they thought they would never enjoy or never need. You wouldn’t believe the enthusiastic replies. Here are some samples of classes they thought were useless and how they feel about them now: