You Majored in What? (31 page)

Read You Majored in What? Online

Authors: Katharine Brooks

It’s a myth that writing is some kind of natural gift bestowed upon only certain people. Sure, not all of us can write like Jane Austen or Maya Angelou, but good basic writing skills can be developed and learned by anyone. So if you’re still in school and you’ve been avoiding those writing-intensive courses, consider taking one. If that’s too intense, take a creative writing course that allows you to write about your interests, or a workshop on journaling or blogging, because practice and feedback from your professor or facilitator will be invaluable to your goal of becoming a better writer. Some colleges even offer business writing courses that would be a great place for you to practice your technique. If you’re out of school, there are still lots of options for improving your writing skills, from getting a book on business writing to taking a Web-based writing class. Even your local bookstore might host writing groups where you could practice your writing and have it critiqued by fellow writers. And by the way, because good writing is good writing, you don’t always have to take a business writing workshop or course if that doesn’t sound appealing. Learning to write science fiction, creative nonfiction, mysteries, poems, or other forms of writing will also develop your business writing skills.

One of the common challenges for students accustomed to writing five-hundred-word essays or twenty-page research papers is the myth that the longer a piece of writing is, the better it is. Good writing isn’t about length. It’s about covering the subject and then stopping. An apocryphal story about Ernest Hemingway places him in a bar where he bet someone that he could write the shortest short story ever written. Supposedly he won the bet by writing a six-word story on a napkin:

“For Sale. Baby shoes. Never worn.”

Now, that’s not exactly a mood lifter and arguably Mr. Hemingway would have benefited from some of that positive mindset in Chapter 3, but in six words he beautifully encapsulated character, plot, and story. You can picture it, can’t you, and fill in the details yourself?

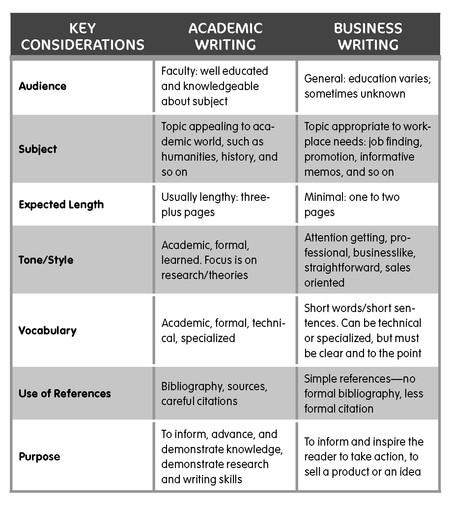

Right now many of you are well versed in academic writing. And that’s good because academic and business writing have many characteristics in common. Good academic and business writers strive for clarity, know their purpose for writing, know their audience and write accordingly, organize their writing in a logical manner, and use the amount of space needed to adequately cover their points. Both types of writing have three key elements: format, style, and content. The table below illustrates some of the differences and similarities between academic and business writing:

In this chapter we’re going to focus on the cover letter, the key piece of job-hunting correspondence. We will briefly discuss other correspondence in the job search process, but the writing knowledge you acquire when crafting a cover letter can be easily transferred to other documents. You are going to use a system for developing your cover letter that will help you avoid writer’s block and keep your letter interesting and focused. You will also learn to avoid the five fatal errors that can ruin your chances of getting a job: a lack of focus in your writing, poor sentence structure and/or bad grammar, misspelled words or typographical errors, an inappropriate style (too casual or academic), and a failure to focus on the reader’s interests and needs.

PREPARING TO WRITE

Your cover letter and other correspondence (including e-mails) related to the job search are a part of your marketing campaign. A good marketing campaign sells the product. Have you ever stood in the grocery staring at the myriad toothpastes available, unable to make a decision because there are just too many? Do I want the whitening or the fluoride or the one with the little speckles or the one that says it has breath freshener? Well, while no one is comparing you to a tube of toothpaste, you

are

selling yourself to an employer who likely has many candidates to choose from, and is sometimes just as confused and overwhelmed as you are in the toothpaste aisle. So it’s your responsibility to make sure they consider you first.

A good marketing campaign is designed to connect you to your future employer by establishing a relationship that will lead to a personal interview and a job offer. Other aspects of your marketing campaign include your résumé, your interview technique, and any portfolio of work you’ve compiled related to your chosen profession. A well-executed marketing campaign can place you miles ahead of the other individuals seeking the same position. With your marketing campaign, you control what is said. You can tell the employer only what you want them to know about you by selecting the most important and relevant aspects of your background.

As you prepare to write your letter, you can expect to spend about one-third of your time

planning

your writing, one-third

writing,

and one-third

rewriting and editing.

You will need space and time to write these documents, so find a place where you can focus and won’t be disturbed. You need to clear all the clutter from your mind—this is not the time to make that to-do list or help your roommate find his or her lost shirt. Try sitting still and breathing for a few minutes before you begin. For inspiration, try checking your career center’s Web site first and read a few of the sample cover letters to get the general gist of what you’ll be writing.

Just don’t copy the sentences verbatim.

Don’t worry; the letter you write will be equally good or, more likely, even better.

In the next section of this chapter you will learn a series of guidelines to help you develop the best possible letter. Stay within the guidelines as appropriate, but remember that your letter is the best place to demonstrate your less tangible strengths, such as teamwork or detail orientation. Develop your own style and let your personality shine through, always keeping in mind the line between creativity and crazytivity discussed in Chapter 8. And just as recommended with your résumé, bring your letter to your career center or writing center for review. If you don’t have access to a career center, let several friends read it and critique it for you.

Before we move to the letter-writing process, the issue of marketing or selling brings up a common concern among students and recent graduates: How do you sell yourself when you’re not even sure you want the customer to buy you? That is, how do you write a compelling letter when you don’t know if this is

the

job—the one you really want? Back to chaos theory: focus on what you know, what you don’t know, and what you need to learn. Right now you probably don’t know enough to know whether it is

the

job. And you probably won’t until you do the interview. The great psychologist Alfred Adler had a wonderful phrase for people who weren’t sure about something. He would say “act as if” you’re sure—in other words, sort of a fake-it-till-you-make-it theory. Because you won’t know if this is

the

job without more information, the best way to get that information is to “act as if” it is and move forward. If at any point in the process you discover it’s not for you (whether it’s the moment you upload your résumé and cover letter to their Web site or ten years after you’ve been working for the organization), you can always change plans. Right now your goal is to get the interview. During the first interview you will be better able to determine if you might be a good match and during a longer second interview at the site you’ll have a much better idea. So let’s get started.

The aim of marketing is to know and understand the customer so well the product or service fits him and sells itself.

—PETER DRUCKER

When conducting interviews for a pharmaceutical sales position, one recruiter hands the students a pen and says, “Sell me that pen.” It is an anxiety-provoking moment for the students, but it is a good test of how quick they are on their feet and whether they have any feel for the selling game. After the interview, the recruiter shares with students the three basic ways to sell a product: tout its features, tout its benefits, or put the pen down and ask questions to help you understand your customer so that you can sell more effectively by tailoring your sales pitch to his or her needs. In a résumé you are generally limited to the first two aspects of selling: your features and your benefits, although you can focus those features and benefits to fit what the employer is seeking. In your letter you have the opportunity to develop the third and most powerful element of selling: establishing or developing a relationship with the reader. Let’s examine those three methods of selling and how they apply to your marketing campaign.

•

Features

are the basic characteristics that define you. They tend to be hard facts or data easily observed or quantified. Features appeal to logic because they provide tangible evidence of accomplishment. Your features might include your major, your GPA, your job or volunteer experiences, and so on.

•

Benefits

are less tangible and are more likely to be your “soft” skills, the special talents and features you bring to a job, such as hard working or team player. You already discovered many of your benefits when you did the Wandering Map and identified your strongest mindsets. Benefits appeal to emotion and logic, particularly if you can back up your statements of talent with examples.

While both of these selling points are necessary, in order to use them effectively the third aspect of sales must come into play: What is your potential employer seeking and how can you build rapport and demonstrate that you fulfill that need?

•

Asking appropriate questions

might seem more applicable to an interview than a cover letter, but as you write your letter, answering certain unasked questions will help you frame your correspondence in a way that will state your qualifications, demonstrate your knowledge of the company and the position, and address any potential concerns. Extend your research, if necessary, to find answers to the following questions about the cover letter you’re preparing to write:

• To whom am I writing? Do I have a specific name and address?

• What action am I hoping this person will take?

• How do my features and benefits fit and support the position, the organization, and/or the career field?

• What features and benefits should I include/exclude from the letter?

• How knowledgeable is this person likely to be about my features? For instance, will she or he already know a lot about my major, or will I need to include a line or two explaining the connection between my major and the position or industry?

• Why do I want to work for this employer and how can I convey my knowledge and understanding of the position or the field?

• How am I connected geographically to this opportunity?

• What else does this person need to know about me?

Writing your letters with these three key sales elements in mind will help you build rapport with the reader and establish your credibility. As in your résumé, you want to develop brief short stories that convey a lot of information in one or two sentences. The reader will know that you have done your research because you will be showing (rather than telling) the reader through your stories and examples.

Perfectionism is the voice of the oppressor.

—ANNE LAMOTT

Following the five-step method presented below will help you avoid the form letter look that is generally rejected by employers and reviewers, and it also has an added benefit: it is designed to eliminate, or greatly reduce, writer’s block. Most students sit down to write their cover letters, and fully aware of the importance of the task, immediately freeze. You stare at the blank piece of paper waiting for the inspiration to start your letter. The five-step process will guide you through your letter in a manner that will destroy the usual causes of writer’s block: the lack of a great opening line, not knowing what information to include, the fear that you will be rejected, and the need to be perfect. You can write the opening line later; in fact, it will likely come to you without effort once you’re in the middle of writing your letter.

Certain characteristics are common to all good letters, and for this reason a sample letter is presented. You may not agree with the example. In fact, you may think it’s terrible and that you wouldn’t write like that. Actually, that’s the point. Writers have to write in their style, not someone else’s, and as long as you’re following the basic guidelines, you’ll produce a document that represents you in the best possible light.