You Might Remember Me The Life and Times of Phil Hartman (33 page)

Read You Might Remember Me The Life and Times of Phil Hartman Online

Authors: Mike Thomas

“Phil is dead!” Brynn says.

“What do you mean, Phil’s dead?” Kathy wonders aloud. “What happened?”

Brynn is unable to speak. Kathy tells her to take a breath.

“I don’t know!” Brynn exclaims. “I’m sick! I don’t remember!”

Then: “Tell the children that I love them.”

“I know you love them,” Kathy says, and asks if Brynn called 9-1-1. The answer is unclear. Distraught like Kathy has never heard her before, Brynn emits a series of bone-chilling shrieks.

When she calms down enough to speak, Brynn mentions that she called Marcy and Ron. She also tells Kathy about Douglas.

“You mean Ronald McDonald?” Kathy asks, using a nickname Brynn bestowed upon him long ago.

Yes, Brynn tells her. Ronald McDonald.

Kathy asks if anyone else is in the house. She needs to talk with someone besides Brynn to better assess the situation and to make sure Sean and Birgen are looked after. Brynn’s crying and screaming persist. Then she says, “I’ve got to go. I gotta go,” and hangs up.

* * *

At 6:32, Brynn’s bedroom phone rings. She answers: “Hello?”

“Hi, this is the police department, um, is Ronnie home?”

“Yes,” Brynn says, “come in.”

“Ma’am?”

“Yes?”

“Is there someone who’s been shot there?”

“Yes.”

“How many people are inside the house?”

“Help me.”

Crying, Brynn hangs up.

The police call back.

“Ma’am?”

“Hello? Hello? Hello? Hello?”

“Ma’am, how many people are inside the house right now?”

“I don’t know.”

“OK, thank you.”

This time the police disconnect.

* * *

Parking on Encino Boulevard near the Hartmans’ front gate, Marcy rings the buzzer a few times but gets no response, so she tries calling Brynn with her cell phone.

Brynn answers: “Hello?”

“It’s Marcy. Open the gate.”

“Over the gate,” Brynn says in a panicked tone. “Over the gate.”

The call ends.

Steve succeeds in opening the gate latch. He and Marcy walk up to the front door, through which they can hear a woman screaming. Inside, wanting desperately to split the scene, Douglas keeps searching in vain for a key. As he does, Steve and Marcy see him through a window. He stares at them and they at him—strangers.

“Who are you?” Marcy asks from outside.

“Ronnie.”

“Let us in.”

“I can’t open it,” Douglas tells them. “It’s a dead bolt. I need a key.”

“Get it from Brynn,” Marcy says.

“No,” Douglas replies. “I can’t. Is there another way in?”

Marcy looks behind her and sees that police have arrived. One of the uniformed officers motions to them. She and Steve retreat from the house.

* * *

Probably rousted by the ruckus, nine-year-old Sean makes his way to where Douglas is standing. (He will later recall that Douglas got him from his bedroom.) They have to get out of there, Douglas says. Fortunately, Sean knows where his parents keep a key for the back door. He retrieves it and they exit. Toting the gun bag in one hand, Douglas ushers the boy outside toward the rear gate and hands over Brynn’s weapon to a couple of waiting officers from the LAPD’s West Valley division. Sean is placed in their protective custody. Douglas also gives the officers a quick rundown of events and informs them that six-year-old Birgen remains inside, possibly asleep.

Once Douglas and Sean are out, several officers make their way into the house through the open west center door. They pass through the kitchen and into the hallway that leads to the bedrooms. Two officers crouch down on opposite sides of the hall. Three more get into similar “positions of advantage,” focusing their attention on the home’s north side, where the master bedroom is. From behind its doors they can hear a female’s moaning and muffled screams.

Brynn is again on the phone with Kathy.

“Take care of my children,” she tells her sister.

Kathy asks what Brynn means.

“Just let them know how much I love them,” Brynn says, inconsolable and sobbing. “Tell Mom…”

She cuts her sentence short as officers announce their presence. One of them calls her by name: “Brynn!”

“I gotta go,” Brynn tells Kathy for the second time, and hangs up.

From Wisconsin, Kathy’s husband Mike calls Los Angeles 9-1-1. He is told that officers have already been dispatched to the Hartman house.

Brynn is done making calls.

Settling into her king-sized bed with Phil’s body, she props herself up against the headboard with a pillow. In her right hand is the Charter Arms .38-caliber five-shooter she has owned for years and fired countless times. Inserting its two-inch barrel into her mouth, she squeezes the trigger. A fatal bullet passes through her brain and lodges in the headboard. Her head slumps toward Phil and her shooting hand drops to the right, almost touching him. Her index finger is still on the trigger.

Although one of the responding officers hears a single gunshot emanate from the master bedroom at around 6:38

A.M.

, he cannot be sure of its origin or target. The response team, therefore, proceeds to clear the other bedrooms, including Birgen’s. Once she is taken from the home and handed off to a female officer who carries her to safety, officers devise a diversionary tactic in order to extricate Brynn with as little risk as possible to her, Phil (whose precise condition at this juncture is unknown to anyone but Brynn), or themselves. It proceeds as follows: Two officers leave the residence and set up outside Brynn’s bedroom window. Its curtains are drawn. “Los Angeles Police Department! Come out with your hands up!” the lead officer, Sergeant Daniel Carnahan, shouts two or three times. There is no response. Using a found brick, one officer hurls it through the glass while simultaneously, inside the house, another forces entry into the bedroom. He is accompanied by uniformed backups.

They encounter a grisly scene. Phil and Brynn are both dead—that much is quickly ascertained. But no one knows why. Outside, just beyond the crime scene perimeter, concerned neighbors mill about worriedly. As media outlets get wind of the developing story, an onslaught commences.

Chapter 17

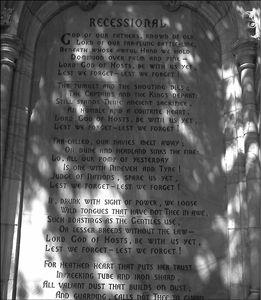

Etching on façade of Church of the Recessional, Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale, California, 2012. (Photo by Mike Thomas)

The circus arrived quickly. Television, print, and radio reporters staked their claims outside the Hartman house, firing questions at LAPD media relations chief Lieutenant Anthony Alba. Along with squad cars and a police van mobile command center, yellow police tape with bold black letters that read

POLICE LINE DO NOT CROSS

blocked the immediate area from cars and pedestrians. A brilliant sun and news helicopters hovered overhead.

As details began to emerge, Phil’s friends and family members—and even those who merely knew him casually or not at all except through his work—sat in shock before their televisions and phoned each other in tears. Jon Lovitz held an impromptu gathering at his home, where he expressed utter incredulity and angrily wondered aloud why this horrible fate had befallen his friend. Others, too, were in a state of drop-jawed, red-eyed incredulity.

Starting around nine

A.M.

, a couple of hours after Phil and Brynn were pronounced dead and forty minutes before their deaths were called in by a West Valley detective, the L.A. coroner’s office began getting phone calls from media outlets seeking details about the case. At 10:20

A.M.

, two members of the coroner’s office—investigative chief Daniel Akin and investigator Craig Harvey—were summoned to the scene. Prior to their arrival, West Valley handed over jurisdiction of the Hartman case to the LAPD’s Robbery/Homicide division, to be co-led by veteran detective Thomas Brascia. He and his colleague, Detective David Martin, formulated an investigative team that processed the crime scene and coordinated with the coroner’s office.

But it wasn’t until 2:26

P.M.

—roughly six hours after they arrived on Encino Avenue—that Akin and Harvey were allowed inside the house to begin examining and ultimately removing Phil’s and Brynn’s bodies. Brascia attributes the delay in part to a “transition of investigative responsibility” and says protocols were set up in ensuing years to allow the coroner quicker access. But Harvey, today the chief coroner investigator and chief of operations, questioned the extended holdup then as he questions it now. “Unfortunately, far too many LEA [law enforcement agency] investigators seem to believe that a death scene is ‘frozen’ in time and therefore they can take all the time they want to deal with that scene,” he explains. “That is only partially true. There are aspects that are frozen to the extent they are not disturbed. However, the human body and biological evidence are changing as the clock ticks.

“The proper management of a death scene is a difficult concept to grasp for some folks. The body, as the most fragile ‘item of evidence’ at a death scene, needs to be addressed quickly and evidence collected. Then the body should be removed from the scene and placed under refrigeration. The body’s value to the death scene is not so important that a sketch or photo would not suffice so that [it] could be removed.”

Still, he concedes, the six hours that elapsed prior to initial examination probably didn’t affect the results of his postmortem work in the Hartman case—though “really, we will never know.”

As more media arrived on the scene, friends and casual acquaintances of Phil’s and Brynn’s were plumbed for information. After Alba’s initial press conference, Commander David Kalish gave another one later in the day to update investigatory developments.

Yes, it was a murder-suicide. Yes, they were still questioning friends and family.

On the day Phil died, Pakistan—neighboring India’s longtime foe—claimed it had conducted five nuclear tests. By late in the day, news of Phil’s tragic death had superseded that alarming announcement on many newscasts across the nation. Numerous friends and some family members learned about Phil’s horrible fate along with millions of others.

JOHN HARTMANN:

Nobody could have expected it. I didn’t even believe it when I first heard it. And I went down there instantly from the phone call that announced it to me to prove that it wasn’t true. But I heard the radio guys talking about it, and guys on radio don’t say things that way unless they’re true. By the time I got to the house, I was concerned about the children and I accepted that [Phil and Brynn] were gone.

I knew it was a murder-suicide before I got there. I was not allowed in the house that day because it was a crime scene. But I went straight to where the children were [the West Valley police station] and started to take care of them. That was the issue.

PAUL HARTMANN (FROM CANADA’S

NATIONAL POST

):

I had gone to town to get some plumbing parts and I was enjoying the ride, but when I pulled up to the house, there was my wife in the driveway. She had this look on her face that made me want to turn the car around.… I went inside and turned on the TV and there was my brother John, in front of Phil’s house, with a police lady. They were wheeling two people away.

NANCY HARTMANN MARTINO:

Mom would have reacted poorly to Phil’s death. Thank God, when he was killed, she was with me up at our ranch in [California’s] Anza Valley. If she’d have been home alone, turned on her TV and seen that, I don’t know what would have happened.

LEXIE SLAVICH (JOHN HARTMANN’S EX-WIFE):

I was moving to Northern California to start my business. And Ohara and [her then-boyfriend] Patrick were driving with me in my Accord, and the [moving] truck was behind us. The minute we pulled out of my parents’ home in Loma Linda, Arizona, that’s when I came across the news. As we headed into the mountains we couldn’t get any reception on our cell phones. But John’s wife Valerie finally reached us when we were approaching Phoenix. I answered the phone and said [upbeat tone], “Hi, Val!” And she said, “I can tell from your voice you haven’t heard the news. Brynn shot Phil and then killed herself.” Ohara was driving and I just blurted out, “Brynn shot Phil and then killed herself!” And Ohara just freaked out. I said, “Pull this car over!” John wanted me to put [Ohara and Patrick] on an airplane to have them take care of Sean and Birgen, and I said, “We are not separating. We’re driving straight to L.A.”

OHARA HARTMANN:

I could tell right away that it was really bad news. Naturally, my first reaction was that something had happened to my dad or brother. I tensed up. My mom turns to me while I’m driving and says, “Brynn shot Phil and killed herself. They are both dead.” I remember breathing in so deep. I knew it was real, but I had no concept of how to process that information. Valerie told my mom that the kids were asking for my boyfriend and I, so we needed to get to L.A. as soon as we safely could. My boyfriend was in the moving truck, so I had to flag them down to pull over on the highway. When I did, I shared the news with him.