You Might Remember Me The Life and Times of Phil Hartman (37 page)

Read You Might Remember Me The Life and Times of Phil Hartman Online

Authors: Mike Thomas

Simms’s next and even greater challenge was to craft the first episode of

NewsRadio

’s fifth season, wherein Bill McNeal’s absence would need to be explained. “I don’t think anyone ever wants to write a so-called very special episode of TV,” he says. “And it was an impossible one to figure out how to write.” Wanting to avoid sappy-maudlin at all costs, Simms jokes that he went for “an enlightened version of maudlin.”

During the shooting of “Bill Moves On,” it was difficult for cast members to fully contain their still-raw emotions, which of course risked killing the comedy. Likewise, during the writing process, Simms knew he couldn’t wallow in melancholy or moroseness. So he decided to extinguish McNeal in one of the most common ways possible: a heart attack. “At least in the fictional world, we could make it so that he died peacefully,” Simms says.

At the start of the episode, which aired September 23, station manager Dave Nelson (played by Dave Foley) frets that his eulogy for Bill had gone on way too long and just plain sucked. He is not disabused of these notions. For inspiration, Simms drew directly from his own angst over having to speak at Phil’s Paramount tribute in July. Simms was also very mindful that each character should have a spotlight moment to say what Bill—and by association, Phil—really meant to him or her. He solved that by having Foley read funny letters McNeal had penned to each of his colleagues. “I remember when I was writing it, thinking, ‘This is half writing and half wish fulfillment,’” Simms says. “I sort of put into Phil’s character’s mouth [Phil himself] sort of comforting everyone from beyond. It felt like even though his character had gone, his voice was still there one last time.”

* * *

That summer, Paul Hartmann set off for the San Francisco area to visit renowned psychiatrist Eugene Schoenfeld, whom he’d tracked down through one of Phil’s friends. Formerly known as “Dr. Hippocrates” when he wrote a widely circulated newspaper column about sex and drugs from 1967 to 1979, Schoenfeld is a veteran physician and bestselling author who provides expert-witness testimony about the effect of drugs in civil and criminal cases.

Aside from offering Schoenfeld the chance to hang out with some of his brother’s remains, an opportunity Schoenfeld accepted, Paul asked the doctor to analyze Brynn’s toxicology report. After doing so, Schoenfeld opined that Zoloft could have been a culprit in the deaths of Phil and Brynn.

He has since changed his mind and now thinks the Pfizer settlement was likely an attempt by the company to stave off more negative press. Schoenfeld has also altered his original opinion about the effect of Zoloft on Brynn’s actions. In short, it had little if any impact. “The toxic mix was the cocaine and alcohol,” he says. “And a very bad mix is alcohol, cocaine, guns, and emotional turmoil.” The author of

Jealousy: Taming the Green-Eyed Monster,

Schoenfeld has studied many cases where that beast raged out of control and wrought havoc. “Jealousy feeds on itself,” he writes. “The more jealous we are, the more insecure we feel. The more insecure we feel, the more liable we are to experience jealousy … Jealousy is essentially a protective reaction based on survival instincts. A solid sense of self-esteem allows us to distinguish between true and false threats of loss.”

Which isn’t to dismiss Zoloft’s potentially serious side effects or the impact it may have had (even at very low levels) on Brynn’s behavior.

Not long after his first visit with Phil and at Paul’s request, Schoenfeld scattered some of Phil’s ashes under the Golden Gate Bridge. Phil’s remains would make their way to several other spots before the year was through.

Chapter 19

Phil, Catalina Island, 1990s. (Photo by Steven P. Small)

September 24, 1998

Nearly four months after his death on what would have been Phil’s fiftieth birthday, thirty or so close friends and family members boarded a sixty-four-foot yacht,

Mantis,

at Dana Point to scatter his ashes in the waters of Emerald Bay off Catalina Island. Part of Brynn’s remains came along as well.

In the preceding months, Paul Hartmann had kept part of Phil’s remains on his farm in Aguanga, California, and divided the rest among several of Phil’s friends for scattering at his brother’s favorite spots around the country. From his catamaran, Wink Roberts sprinkled Phil along the Malibu shore. More of Phil went to former Rockin Foo band member Ron Becker in New Mexico and to the top of California’s Mounts Whitney and San Jacinto.

The sea was choppy and the sky overcast as

Mantis’

mostly cheery throng of travelers sped toward their destination, about twenty-six miles slightly northwest of the mainland. “You couldn’t be somber about Phil,” Clif Potts says. “Because when you talk to each other about Phil, you’re always laughing about something he did. The predominant point was not that he got shot. It was what his life was and how cool it was when he was around.”

Besides six of Phil’s seven siblings (Sarah Jane was not present) and his deeply aggrieved mother Doris, several Groundlings made the trip. Among them were Laraine Newman, Phyllis Katz, Jon Paragon, and Lynne Stewart. Cassandra Peterson was unable to attend, but her husband Mark Pierson was there. Close friends Potts, Sparkie Holloway, Britt Marin, Floyd Dozier, and Wink Roberts took part in the celebration, too. And it

was

a celebration, one that John Hartmann likens to “a floating Irish wake.”

Everyone wore purple-and-white leis fashioned from what Paul recalls were fragrant plumeria flowers, and a lovely set of coconut ta-tas was passed around (with its complementary grass skirt) for clowning purposes. As Catalina came into view off the port bow, Paul’s wife Christie pressed the coconuts to her chest and belted a bit of “Bali Ha’i” from Rodgers & Hammerstein’s musical

South Pacific

. Inside and out, laughter and smiles abounded. Classic rock tunes from Pink Floyd and the Grateful Dead played over the motor’s loud whirring. A large American flag fluttered and snapped in the wind. On the ledge below a salt water–dappled cabin window, encircled by flowers and another lei, rested a framed photo of Phil as the seafaring not-so-ruffian Captain Carl from Pee-wee days. Stewart, as Miss Yvonne, posed lovingly by his side. Another glossy, of Phil handsomely be-suited and hosting

Saturday Night Live,

adorned an interior wall.

Perched at the stern, his thatch of unruly graying hair and matching beard swirling in the breeze, Paul Hartmann animatedly held forth about matters cardiologic. “If you’re depressed, angry, or sad,” he explained to several listeners, “you’re sending a stress signal to the heart.” The responding signal, he went on, hits the brain center that controls production of DHEA—the so-called and controversial youth hormone. Aside from counteracting the process of aging, Paul explained, it also helps maintain the heart’s elasticity. “People who are chronically angry or carry animosity toward [others],” therefore, “turn their hearts into leather.” But he claimed behavioral health types had devised a simple preventative measure called

freeze framing.

“Every time you get into a negative thought cycle, like depression or anger or animosity toward a fellow worker, you stop yourself consciously for one minute and you think about a loving experience or a time and place in your life where you were very happy and joyous.”

For Phil, Catalina

was

that place—“a happy place.” At Catalina, he was fully himself. At Catalina, professional pressures dissipated. At Catalina, discord gave way to harmony.

Upon its initial docking at Catalina’s isthmus,

Mantis

picked up several other passengers—including Jon Lovitz, John Hartmann, and John’s wife Valerie, who had helicoptered over and then driven from Avalon. After they climbed aboard, champagne corks popped and bubbly flowed. If one was so inclined—as Phil almost certainly would have been—God’s herb was available for recreational toking. And the cuisine was top-notch: a catered feast of salmon (full name: Salmon Rushdie) and herbs-and-olive-oil-marinated chicken breasts and fresh fruit.

Shoving off from the isthmus, Phil’s gang then motored through smooth waters to where he’d again be at one with the ocean, as he had been while surfing and scuba diving and snorkeling and sailing. He was arguably even more content in the water than he was onstage, and so it made perfect sense that he should rest in peace where he’d been most

at

peace. But there was one small hitch: Although Phil had asked Marin to scatter his ashes in the shallows around Indian Rock, doing so required the use of a dinghy, which was disallowed for liability reasons. Adjacent waters had to suffice.

“Before we send Phil on his final journey, we’ll pass this basket around,” Phil’s sister Mary announced over the soothing strains of a pan flute. She cradled a small, square wicker-like container nestled in a light-blue cloth. In it, beneath a layer of flower petals, was Phil’s white-ish pulverized remains. Those who wished to do so, Mary said, could hold the basket and memorialize him aloud or silently. Paul went first.

“Today,” he began, “we are here to spread the ashes of Philip Edward Hartman.” His tone was steady and his manner relaxed as he recalled surfing with Phil, their hours spent laughing in the same bedroom on La Tijera, Phil’s workaholic ways, and his “sensitivity” to friends.

“I loved Phil and I will always love him,” Paul concluded. “And I’ll miss him really a lot.”

It was Lovitz’s turn next, but he could not speak. Staring down at the dust that had once been his cherished friend and idol, he quietly said, “I don’t know. These are his ashes, but it’s not him.” Others spoke, some through tears, of God and the universe and how “Phil is a spiritual being now.” John—descended from his solitary perch on the boat’s upper deck—thanked Phil for giving him two especially useful books:

Zen Macrobiotics

and

Yoga, Youth and Reincarnation.

Both, he said, had changed his life and “made me a better man.” Wink Roberts fondly recalled sailing with Phil, and Sparkie Holloway garnered grins and giggles with his story about Phil’s Lyndon B. Johnson impressions in high school.

At last it was time to perform the act for which they’d all gathered. Again, Paul took the lead. Standing on a platform at the stern, his bare feet submerged in seawater, Phil’s baby brother—the one he’d squired to Disneyland and jealously watched ride his first-ever wave all the way to the beach—was again calm and collected. “Well, Phil,” he said, regarding his brother’s ashes, “we’re going to release you into the elements.” Paul then added, with a pirate-y growl, “And like Captain Carl, who longed to go back to the

briny blue

, so is Phil.” And with that, it was man overboard. Seconds later rays of sunshine pierced the overhead gloom.

Back on deck and clasping a wooden cube containing Brynn’s ashes, Paul spoke in a tone that was devoid of animosity, anger, or sadness. “I forgive Brynn and I send her love and I wish her well on her journey. And I pray for her.” He then passed the cube to Brynn’s visibly pained friend Judy, who offered a brief tribute of her own before reuniting husband and wife. Some grumbled about the comingling.

A short while later, its mission accomplished,

Mantis

headed home. As her passengers talked—about Phil, about life—the Grateful Dead’s 1970 album

American Beauty

blasted start to finish a couple of times over. “Well, another successful crossing!” Paul declared in a goofy voice before letting loose a maniacal high-pitched laugh.

The journey back, like the voyage there, was not a solemn one.

Epilogue

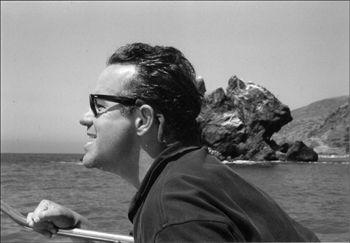

Phil at Catalina/Indian Rock. (Photo by Mark Pierson)

September 24, 2013—Phil’s 65th birthday

Descending from Banning House Lodge, a venerable bed-and-breakfast perched high on a hill in the less touristy section of Catalina Island called Two Harbors, Phil’s confidant and fellow outdoorsman Britt Marin and his guest rented a bright yellow Malibu II double kayak at a harbor-side shack, stashed scant supplies, dragged their rig into the blessedly calm ocean, and pushed off to scatter Phil’s mortal remains in fifteen to twenty feet of water around Indian Rock in Emerald Bay—just as Phil had requested. Not surprisingly for Southern California at that time of year, it was a brilliantly sunny day with temperatures in the mid-to-upper seventies. Perfect.