You Might Remember Me The Life and Times of Phil Hartman (5 page)

Read You Might Remember Me The Life and Times of Phil Hartman Online

Authors: Mike Thomas

On the funny front and as something of a surprise to his mother, who had always pegged him as “serious,” Phil and a female classmate were voted Westchester’s Class Clowns. In a photo of the jesters, whose caption misspells his last name as “Hartman,” Phil folds his arms over a puffed chest in a comically cocky pose. The dropped

N

and arch attitude prophesied things to come.

Chapter 3

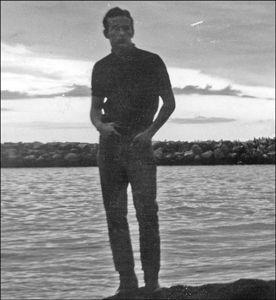

Phil, late 1960s. (Courtesy of the Hartmann family)

For many thousands of U.S. troops stationed in Vietnam and those waiting to be transported over, the summer of 1966 wasn’t exactly a high point. But even as President Lyndon Johnson steadily increased America’s military presence in that far-off jungleland (the draft didn’t start until late 1969), life in surf-centric Southern California remained quite idyllic. The Beach Boys still held considerable sway on the pop charts, despite anemic U.S. sales that May of the group’s experimental (and eventually lauded) album

Pet Sounds.

William Jan Berry, of the surf-rock duo Jan & Dean, was in the news after being critically injured that April in a car crash very close to Dead Man’s Curve in Beverly Hills. Ironically, he and his musical cohort, Dean Torrence, had scored a hit two years prior with a tune of the same name.

Cruising around in Holloway’s 1964 Pontiac GTO, Phil and Sparkie did some “really insane things” of their own, such as straddling the running boards of their respective rides while tooling up and down Manchester Boulevard. Mostly, though, they hung out and smoked cigarettes. Or watched television. Or played “squiggles.” Completed illustrations included a toothless old woman and a bleeding chicken fleeing a blood-drenched ax. And, of course, there was surfing. With the craze in full-bloom, a new generation—of fad-following

Gidget

fans and die-hard disciples of surfer-rebel Miki Dora—was loading up its Woodies with Dewey Weber, Gordie “Lizard,” and Greg Noll’s “Da Cat” boards (named after Dora, who was nicknamed “Da Cat”) and setting off to drop in, hang ten, and eat it courtesy of bodacious waves all across the Southern California coast. Phil and Holloway were among them. “Surfers always looked down on jocks because they were stupid enough to stay after school while we were at the beach,” Phil once said.

Mornings were always best. On Friday and Saturday nights, after divesting themselves of their respective female companions, if there were any, Phil and Holloway regularly reassembled at a drive-in called Tiny Naylor’s on the corner of Manchester and Sepulveda in Westchester. It was a social hot spot through whose large windows hangers-out could keep tabs on new arrivals and passersby could scan the clientele before entering. “We’d sit there and chew the fat and then decide, ‘Oh, shit, let’s go surfing,’” Holloway says. An hour or so later, after fetching their boards, they reconvened, loaded gear into a ’61 Ford Station wagon Holloway had at his disposal, and headed out to a favorite surf spot near the Ventura County line. “Half the time we’d almost fall asleep and kill ourselves running off the road,” Holloway says. Parking on the beach, they waited until the sun rose and then paddled out—Holloway on his stomach, Phil on his knees (a style that was considered much cooler). “Phil was actually good at it,” Holloway says, “and I was just sort of there.” As Paul Hartmann remembers, Phil’s repertoire of surfing techniques on his Dewey Weber board included walking the nose, hanging five and ten, cutbacks, and frontside/backside off-the-lips, to name just a handful. “You’d go every chance you got,” Paul says.

For Phil and countless other SoCal surfers, however, riding waves was more than a sport or mere pastime. It went much deeper than that. As former

Surfing

magazine and current

Surfer’s Journal

publisher Steve Pezman explains in David Rensin’s oral history,

All For a Few Perfect Waves: The Audacious Life and Legend of Rebel Surfer Miki Dora,

“Some waves are too simple: not a drop of water is out of place, it’s easy to ride. But the Malibu wave has different modes, and although it’s dependable in some ways, it’s never the same twice. It has enough complexity and variation to hold one’s attention, almost like a human relationship. When you find a wave like that, you invest in it.”

Hours before the surf was up, Phil and Holloway sometimes perched atop a lifeguard tower on the beach and gazed into the sparkling night sky. Topics of discussion were wide-ranging: How many stars were there? How big was the universe? Who was God? What did the future hold for humankind? “All the things you want to solve when you’re seventeen or eighteen,” Holloway says. And when Holloway told Phil that as a boy he’d seen four smaller spacecrafts emerging from an alien mothership, “there was no doubt with him that I’d seen what I’d seen.”

“He was hopefully spiritual,” Holloway says, “that there’s got to be something more besides us.”

That fall, around the time he turned eighteen, Phil enrolled at Santa Monica City College as a full-time student and commuted to classes from his parents’ home in Westchester. Holloway entered as well and joined the football team. During his freshman zoology class, Phil kept a partially dissected rat in the freezer at home. One day Paul walked into the house and found Phil at his drawing board. Only he wasn’t drawing. Instead, Phil had taped the rat’s severed hind legs to his fore- and middle fingers and, employing the table as a tiny dance floor, was performing a soft-claw rendition of “Tea for Two.”

With another sophomore named Wink Roberts, Phil also took a public speaking course. An early bloomer when it came to showbiz, Roberts had already filmed a movie with Jacqueline Bisset. “Phil was so envious,” Roberts says, “and he was so talented and wanted so badly to get into the industry.” For the time being, though, he polished his skills where he could. In their speaking class, Roberts says, Phil always added “a funny twist” no matter the topic of his presentation. “He could never walk into a room and be happy if he couldn’t make people laugh.”

Outside of classes, they skied together at Mammoth Mountain, located about thirty minutes from campus in the Sierra-Nevada range of Eastern California. It was there, during a visit to Mammoth’s Hot Creek—a geothermal volcanic spring—that Phil gave a public performance Roberts still remembers vividly. On this particular evening, scores of gatherers parked their cars, walked down a long dirt road, doffed clothing, and hopped naked into the 100-degree water with their wine and beer and joints in hand. “The fog was so dense that you couldn’t see the hand in front of your face,” Roberts says, but the moon shone brightly. At one point, Roberts turned to Phil and said, “Do your Eric Hearble,” a reference to the quirky 1964 short story by John Lennon. Phil obliged with a dramatic reading: “One fat morning Eric Hearble woke up with an abnorman fat growth a bombly on his head.”

“I’m telling you that within thirty seconds, this entire creek was quiet,” Roberts says. “He had all of these strangers in the palm of his hand, and all that they had was a voice in the dark and fog.” Upon reciting the Lennon ditty, Phil went on to do movie star impressions, jokes—the usual. “And for two hours,” Roberts claims, “he had this audience riveted to every word he said. Two hours where no one ever even saw his face or knew who he was.” When Phil’s set came to a close, Roberts says he announced, “Ladies and gentlemen, that was Mr. Phil Hartmann, and someday he’s gonna be a big star! Remember this night!”

* * *

Phil’s other courses throughout his four semesters at SMCC included American Government, U.S. History to 1865, Beginning Drawing, Beginning Oil Painting and, oddly for such a die-hard aqua man, “non swim” phys-ed.

He repeated Reading and Composition during his first and last semesters, his evolving worldview and sense of humor coming through in disjointed and grammatically screwy essays that received mostly mediocre marks. In “Soul Reality,” Phil explained how the soul imbues man with “an ability to sense truth beyond his own intellect, a reality too awesome to understand intellectually, yet so powerful we embrace it blindly as a babe.” Philosopher Phil went on, if a bit incongruously: “There are no practical lovers. Love is not controlled, it controls. The soul literally takes us beyond ourselves, as does love.”

In “A Harmony of Life” he mused about why men and women are attracted to one another, concluding that attraction goes “beyond social needs and the desire to be approved of, beyond overcoming guilt and beyond sexual gratification.”

An uncommonly high B was awarded for his comedic essay titled “The 1969 Croceledillo Is Here,” which purported to be “the first in a series of reports on America’s greatest achievement in crossbreeding” involving a crocodile, an elephant, and an armadillo. The bizarre hybrid, he explained, weighed “some two tons” and was invented to replace the “Automobilis Americis”—cars. “The loss of air pollution alone,” he reasoned, “will make the whole effort worthwhile.”

In the tonally disparate “Why I Will Live After Death,” Phil pondered the afterlife much as he did with Holloway on surf outings. “I guess each man looks for his own proof or disproof of life after death,” Phil wrote. “My proof is simple. When I look at a star-lit sky, I am awed by its infinite beauty and mystery. I cannot perceive the phenomena [sic] and on the same [level] believe that man is the ultimate being in the universe.”

Between essays and other coursework, Phil poured his aching and sometimes loopy heart out in letters to high school confidante Kathy Kostka, who’d begun attending Arizona State. In a doodle-filled missive dated January 14, 1967, he addressed her as “Kasha” and excitedly broke news of his split with a girl named Marilyn: “I guess it’s about time. It was hard, sad, confusing—but final. It’s all over now and I am back to my old self (unfortunately) as you can see. Are you coming home on semester break? Dear God I hope you are. The sunsets have been absolutely out of control!” Upon signing off (“Love forever, Phil”), he signed right back on. “Did you really think that was the end! Ha ha ha. I’m sorry, I will continue to bore you, on purpose. Kasha, I look at your picture as I write. In your eyes I see the beauty and passion of a human being full of soul and the love of life … I feel my mood changing from joking to something else.” As the hour grew later, Phil grew goofier—confiding that he probably couldn’t pen “such an offbeat letter to anyone else.” At one point he simply began listing thoughts that popped into his brain: “Your face is beautiful, and warm, its warmth radiates around me.” And: “I just want to look into your eyes again … and let them talk.”

But Kathy knew that Phil’s suddenly intensified romantic feelings for her were as much about the physical distance between them as anything else. “He liked the chase and the longing,” she says, “more than he liked being in a relationship.”

* * *

In the spring of 1968, a few months before Phil turned twenty, his brother John and a couple of business partners—music manager Skip Taylor and future Los Angeles International Film Festival founder Gary Essert—joined forces to open a cutting-edge live performance venue they dubbed the Kaleidoscope. John had by then left his agent job at William Morris, where he handled such acts as Buffalo Springfield, Chad & Jeremy, and Sonny & Cher. During the Kaleidoscope’s evolution, he booked shows for the rock group Canned Heat, whom Taylor managed. John and his cohorts had tried to open the Kaleidoscope a year or so prior, but various roadblocks impeded progress. When they finally secured the former Earl Carroll Theatre, at 6230 Sunset Boulevard, work began to transform it into what John and his fellow founders envisioned as the hippest joint around for jam sessions, dollar film “orgies” (classics, current fair, cartoons, newsreels), and even wild political events. With the help of hired hands—including a struggling young actor-carpenter named Harrison Ford—they installed a dance floor made from the planks of a nearby shuttered bowling alley, two interconnected round and rotating stages, and a finely woven scrim onto which overhead projectors beamed artist-swirled images of water and oil. One especially crazy event, dubbed the “Independence Day Spectacular,” included a sketch in which comedian and mock-presidential hopeful Pat Paulsen (who’d chosen the Kaleidoscope as his mock-presidential campaign headquarters) played George Washington to rock-folk queen Mama Cass’s Betsy Ross. As John recalls it, Paulsen made his entrance on a horse and the show ended with indoor fireworks. Throughout the evening of “total insanity,” Chad Stuart of Chad & Jeremy conducted a twenty-five-piece band, vaudeville acts (bell ringers, fire-eaters) wowed the crowd, and someone coaxed a pachyderm onstage. Maybe it was fortunate the all-ages club served no alcohol. “We wanted to keep it open to anybody and we kept the ticket price very low,” John Hartmann says. “We were probably, stupidly, hippies in trying to keep it civilized and not expensive, but we had a great time.”

So, too, did Phil on the handful of occasions he dropped by to chill and check out the acts. On any given night, the club’s lineup featured Jefferson Airplane, the Grateful Dead, Canned Heat, Tiny Tim, Steppenwolf, Genesis, the Doors, and a host of other already famous or soon-to-be famous bands. When Holloway tagged along, hijinks ensued. If they weren’t posing as roadies for the featured act, Phil was pretending to be an English gent and Holloway a deaf-mute. One time, Phil convinced a few girls that Holloway was a stuntman for Warner Bros. who had just appeared in an episode of

Bonanza.

The girls, as Holloway remembers it, were all agog.