You Might Remember Me The Life and Times of Phil Hartman (6 page)

Read You Might Remember Me The Life and Times of Phil Hartman Online

Authors: Mike Thomas

Besides comedy, surfing and shenanigans, Phil and Holloway shared a common interest in cigarettes. But on February 28 and 29 in the leap year, 1968, both swore separate written oaths to kick the habit. Using a fine-tipped black marker, Phil elaborately stated his intent in neat cursive.

“I solemnly promise, upon my honored word, that I will quit smoking tobacco cigarettes down to the slightest, secret puff,” it began. Penalties for breaking the pledge included: paying Holloway $10; letting him “slug” Phil in the arm twice; footing the entire bill for a double date; washing and waxing Holloway’s car and putting gas in its tank; and purchasing for Holloway two cartons of cigarettes—his choice of brand. Phil swore to the truth of the aforementioned “under the God of my choice” and signed his name: Philip Edward Hartmann and Philip Edward John Hartmann/Future Unlimited.

Holloway approved the document by inking his own signature at 1:34

A.M.

on February 29. Their respective contracts were folded up and stashed in an empty Newport Menthols carton. As for their mutual abstention, it lasted maybe a week before both parties admitted to cheating and the whole thing went up in smoke.

* * *

By the spring of 1968, tar and nicotine must have seemed safe in contrast to what Holloway’s future had in store. He’d recently dropped out of Santa Monica College after injuring his ankle during football and being dumped by his girlfriend. While still in school, he’d received a couple of draft deferrals. Knowing he was unlikely to get another and aware that the Marine Corps offered a shorter enlistment term than other military branches—two years instead of three—Holloway signed up to serve rather than leave things to chance and the U.S. Government. Starting that June, he spent a couple of months at boot camp in San Diego followed by Advanced Infantry Training at Camp Pendleton (also in California) before heading to Vietnam. Stationed there at a heavily protected base outside Da Nang dubbed “Monkey Mountain” (Hill 647, officially) by the soldiers, PFC Holloway worked briefly in supply and pulled guard duty. Eventually he ended up in a financial role, handling multimillion-dollar military accounts.

That fall, around the time Holloway was settling in overseas, Phil earned a respectable (and higher-than-average) B for his English essay “My Point of Rebellion.”

“No political situation merits more dissension than the intervention of the United States in the Vietnam revolution,” he wrote, going on to blame greedy corporations and the greedy people who ran them for helping to fuel the war effort in a grab for profits. He also questioned what seemed to him an unnatural fear of Communism. As for America’s meddling in a “sovereign nation,” Phil concluded, it was entirely unwarranted—akin to if another country had assisted the British against the colonies during the Revolutionary War.

The many letters Phil and Holloway exchanged between the summer of 1968 and the fall of 1969, when Holloway returned home, were typically lighter in tone. Holloway’s missives to Phil have been lost to time, but all of Phil’s survived. At turns funny and poignant, they are rife with wisecracks and doodles and personal revelations. “Are they teachin’ ya to kill?” reads the caption beside a goofy-looking G.I. character wearing a “Sparkie” T-shirt and clutching his rifle in proper military fashion. In another drawing, Phil adorns a peace sign with the words “Peace—Love—But Mostly Money.” And in its center: “Ha Ha Ha Ha.”

Phil went on to tell Holloway about his new 1961 VW panel van. Purchased from “a desperate guy” with money ($430) Phil had made from hawking his motorcycle (for $450), it “runs bitchen.” As part of its interior revamp, Phil installed a twin mattress in back. He also mentioned his plans to attend SMCC for another semester “and then I’m gonna ski my brains out till I get drafted, I guess.” The Kaleidoscope’s temporary shuttering due to “legal problems” came up as well. And on the surfing front, Phil informed Holloway, seven-foot “miniboards” were all the rage. He signed off “The Real John Wayne,” then added, “Why don’t you send me a deep soul-packed letter, you crusty bastard?”

Although still a non-citizen, Phil’s status as a U.S. National between the ages of eighteen and twenty-six made him fully eligible for the draft. According to Kathy Constantine (Kostka), he was ambivalent about going were his number drawn. They even discussed running off to Canada together. “He was just toying with getting out of there,” she says. “He definitely did not want to be drafted.” While the possibility loomed, Phil was free to find himself in the mountains of Mammoth and the waves off Malibu. Upon completing a fourth semester at SMCC, he also submitted an application to attend the University of Hawaii. Before shoving off, however, he planned to spend five months bumming around and, he hoped, cleaning up his act.

“Let me know how you’re doing,” Phil wrote to Holloway on November 30, 1968. “Do you have a lot of free time? Do you have access to a Bible? I know if I was in your boots [“shoes” is crossed out] I would especially be able to get right into it, Spark. But I do here too. There’s a kind of war here for me. It’s a war to make myself into a pure, clear thinking, clear acting and clear meaning person, and that means no ‘kicks.’ It is a war too because I am surrounded with ‘freaky people’ who make it hard to go straight. But I am overcoming this, as I will overpower everything. That’s the way I feel now because I’m not depending on myself. My inspiration comes from outside of me. It is stronger than men. It made them. We’ve both got many things to do til we meet again Sparkie, but let’s keep the letters going. It’s good for both of us.”

A couple of weeks later, Phil put pen to paper once again. He was enjoying his time on the slopes of Mammoth, he told Holloway, but a move farther north to live secluded in the Santa Cruz Mountains would be just the thing to extricate him from “this city and its corrupting influences.” He mused about chilling out there and selling his landscape paintings to earn money. There were also a couple of colleges up in those parts, Phil continued, one of which was dotted with pine forest cabins. He was considering adopting a macrobiotic diet as well, though he admitted doing so was difficult with competition from his mom’s cooking.

As 1969 dawned, Phil wound down his ski bumming and readied to cross the Pacific for school at the University of Hawaii—even though he had yet to be accepted. In order to partially replenish his ever-dwindling personal coffers before relocating, he put his van, Head skis, and acoustic guitar up for sale. “It’s Hawaii for sure,” he proclaimed in a letter to Holloway dated March 7. At the moment, he was preparing for his draft physical on which he would hopefully get a “1-Y,” which meant he’d be qualified for military service only in the event of war or national emergency rather than immediately available to serve like those who received a “1-A.”

Upon letting his hair grow long and bushy “like Jimi Hendrix,” Phil decided it was a bit too extreme and chopped most of it off—down to an inch and a half. His facial foliage, however, was beginning to sprout anew, and soon he’d have another full-blown beard. But his scraggly, devil-may-care style blended in nicely with that of his shaggy new rock ’n’ roll friends, several of whom played in a Malibu-based band called the Rockin Foo. Managed by Phil’s brother John, the Foo took their handle from a Chinese symbol meaning joy, played what used to be described as “psyche garage country rock,” and were on the cusp of recording their first album. Meanwhile, the guys gigged around town (they played on bills with Alice Cooper in March) and elsewhere, cultivating a wider following. He’d seen them a couple of times, Phil informed Holloway, “and they are just super bitchen.” As it turned out, the Foo dug

him

, too.

By early May, Phil had sold his van for $450 and received a tax refund of $121.31—hardly a fortune but enough to get him to Hawaii. If he ever left. The University of Hawaii persisted in “giving me the runaround,” he groused to Holloway, and the whole ordeal was making him anxious. He even reapplied, upon the school’s suggestion, as a foreign student, but that proved fruitless since he was already a permanent U.S. resident. So he waited. And waited. Nothing. Phil aimed to be an art major with a concentration in photography, he wrote, “if I can just get in the fucker.”

* * *

For a month or so Phil had been living with his brother John and the Foo clan—initially a trio made up of Lester Brown Jr., Michael “Raccoon” (Clark) and Wayne Erwin—in a small Hollywood house on North Fairfax, and traveling with them locally as one of two equipment managers. He also worked with college pal Wink Roberts at an advertising firm called the Boardroom, where Phil operated a stack camera and photo-typositor machine to create print ads for such clients as Telluride ski resort.

That same year, after Kostka got married, Phil came to terms with the fact that he and she would never be an item. Upon learning of her engagement, Phil had tried to persuade Kostka not to get hitched, but to no avail. And maybe that was just as well. “I have been relieved of that big sex hang-up that I had with her,” he confided to Holloway, “and now we can be really close friends without my dick popping out of my pants. I realize now that’s really how I’ve always wanted it. Her married, I mean. Not my dick poppin’ out, you dirty jarhead.” Phil hadn’t heard from the draft board, either, so he assumed all was cool. It was about to get cooler.

In late May, he fired off another missive to Vietnam. “This letter is going to flip you out, believe me,” it begins. On May 24, he’d made “a decision that will no doubt change my life.” Instead of attending the University of Hawaii, which still hadn’t approved his application and probably never would, he accepted an offer (a plea, really) from John to become a full-time Rockin Foo roadie. John was thrilled to have him on board and closer to home. When he first heard about Phil’s Hawaii plans, John says, “I felt this incredible sense of loss. And I said, ‘Don’t go to Hawaii. You’re just going to become a surf bum. Come with me—come and become a rock ’n’ roll bum.’” So Phil stayed put.

It surely helped that he would earn a nominal fee for his toil, as the band had just received a $25,000 advance for their debut album on Hobbit Records. With part of the money, John leased a bigger home at 23758 Malibu Road. Featuring a yard, garage, patio, and detached front coach house, the three-bedroom pad was situated in the trendy and celebrity-dotted Malibu Shore Colony development and cost only $600 a month during the off-season ($1,700 during prime months). Originally constructed as a vacation home, it was poorly insulated and, Brown says, “built like a barn.” On the plus side, it had a fireplace and the location was unbeatable. “Right on the beach,” Phil wrote to Holloway, “a few steps away from the best surfin’ spot in California. FUCK!!” Best of all, he’d have his own dwelling: a detached ten-by-twenty, two-room cabana in back that had previously (supposedly) been occupied by Brian Wilson of the Beach Boys and whose rear-facing picture window looked out onto the Pacific. Paradise. “I have a job … for people I love,” Phil gushed in a late May letter. “In [re]turn, I get a house and a van and a beginning in the art field. Also all the thrill of really being on the inside of the rock scene. I’m a born long-haired man. That is the lifestyle I love. I have no qualms about the decision I made. It all seems like a dream, but it’s really real.”

* * *

When Kathy occasionally ran into Phil, she saw more than a wide-eyed rock ’n’ roll wannabe. “He was acting like he was already hot shit,” she says with a laugh. “And it was not the person I knew—down-to-earth Phil. He was somebody trying to portray a celebrity.”

Well, there

were

groupies, and in one of his letters to Holloway Phil did a bit of good-natured bragging. “What is every kid’s dream in America?” he asked rhetorically, teasingly. His answer, tucked away in the bottom margin: “I balled a Playboy Bunny. I won’t give you the details in the mail, but pal it was beyond your imagination.” Still, even as he revealed and reveled in that momentous event, another young and free-spirited chick sat beside him—one of the many “groovy groovies” who wandered in and out of the Foo compound. Before long, though, Phil’s seed sowing would cease (for a couple of years, anyway) and he’d only have eyes for one.

Chapter 4

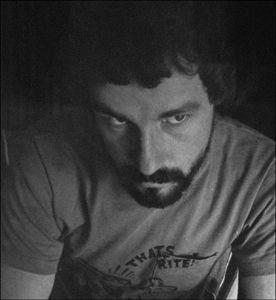

Phil, Malibu, early 1970s. (Photo by Steven P. Small)

Malibu Colony in the 1960s was exclusive but unassuming in contrast to the pricey paradise it would become. There were stars and swell homes, as there had been since the 1930s, but far fewer of the behemoths that today occupy the area’s private beachfront plots. For a while, in fact, the Colony was served by only one bank (Bank of America) and one diner (the Malibu Diner). During the period Phil called it home, neighborhood luminaries included Steve McQueen, Henry Gibson, and Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor; the latter two rented singer Bobby Darin’s four-story house not far from Phil’s little cabana.

I Dream of Jeannie

and future

Dallas

star Larry Hagman lived close by, too, often lounging in his large Jacuzzi and playing Frisbee on the sand. For whatever reason, Hagman took a shine to Phil. Often with other mates in tow, they attended the Malibu Grand Prix together. They also spent much time soaking in Hagman’s hot tub and smoking pot. Back then, ganja was available in abundance—at the Foo house, a cake pan was always stocked with choice weed and rolling papers—and Phil readily partook. Nevertheless, says Foo member Michael Clark, “Even in those wild years when we were tripping on acid and smoking joints every five minutes,” Phil always demonstrated good sense and was “very much under control.” Adds John Hartmann, “He was not vulnerable to the fuel aspect of [drugs]. It was a toy, sometimes a tool, but it was never a fuel.”