Your Brain and Business: The Neuroscience of Great Leaders (14 page)

Read Your Brain and Business: The Neuroscience of Great Leaders Online

Authors: Srinivasan S. Pillay

Concept 3

Attachment anxiety has been linked to the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis in humans. The HPA axis is involved in many functions, such as stress regulation and maintaining mood states. One study found that attachment anxiety was positively correlated with cortisol response to stress and negatively with the cortisol response to awakening.

82

What this implies with regard to leaders is that leaders who are unable to form secure attachments have a greater cortisol response under stressful situations. The HPA axis is overactive.

82

Concept 4

Furthermore, people who tend to withdraw from close relationships respond spontaneously to a lesser extent to negative interpersonal emotional signals than securely attached individuals.

83

That is, their brains (somatosensory cortex) appear to not pick up negative emotional signals as well as securely attached individuals.

Concept 5

Insecurely attached individuals also activate the amygdala and reward brain differently. Activation of the striatum and ventral

tegmental area (reward brain) was enhanced less to positive feedback signaled by a smiling face in participants with avoidant attachment, indicating relative impassiveness to social reward. Conversely, a left amygdala response was evoked by angry faces associated with negative feedback, and correlated positively with anxious attachment, suggesting an increased sensitivity to social punishment. Thus, the brains of insecurely attached leaders (leaders who display this attachment style in questionnaires) are less sensitive to reward and more sensitive to punishment.

84

The application:

The attachment styles of leaders are critical when it comes to enhancing their leadership effectiveness. Managers, leaders, and coaches can reflect on how alignment within their organizations and in their partnerships requires the cooperation of their brain’s abilities to ensure secure attachment. Insecure attachments (anxious and avoidant attachment styles in relationships) increase the stress response within the leader and also decrease the leader’s brain sensitivity to reward while increasing the brain sensitivity to punishment. (Decreased reward and increased punishment are additive in the brain.) Their attachment style also makes them less sensitive to negative interpersonal signals. This means that even when their brains overreact to punishment, they don’t feel other peoples’ pain as much as securely attached leaders do. Coaches can help leaders determine their attachment styles, with a view toward developing new learning around reading emotions as well as skills around people engagement so that this leadership style does not trickle down into the organization, affecting its integrity as a whole.

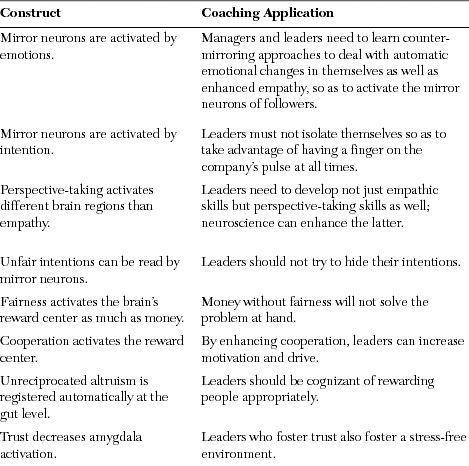

Table 3.1

below summarizes some of the concepts on social intelligence as it applies to managers, leaders, and coaches.

Table 3.1. Social Intelligence through the Neural Lens

Conclusion

Social intelligence is far from a soft skill for leaders. It is critical in the execution of teamwork, in understanding how a company runs, and in understanding the needs of customers at a deeper level. Goleman’s view is summarized in his seminal article: “The only way to develop your social circuitry effectively is to undertake the hard work of changing your behavior.... Companies interested in leadership development need to begin by assessing the willingness of individuals to enter a change program. Eager candidates should first develop a personal vision for change and then undergo a thorough diagnostic assessment, akin to a medical workup, to identify areas of social weakness and strength. Armed with the feedback, the aspiring leader can be trained in specific areas where developing better social skills will have the greatest payoff. The training can range from rehearsing better ways of interacting and trying them out at every opportunity, to being shadowed by a coach and then debriefed about what he observes, to learning directly from a role model....”

4

Thus, social intelligence development is critical to any leader. By reflecting on this and much more extensive knowledge of social intelligence, leaders can improve their own performance and the performance of their companies.

References

1. Thorndike, E.L., “Intelligence and its use,”

Harper’s Magazine

. 1920. p. 227–235.

2. Albrecht, K.,

Social Intelligence: The New Science of Success

. 2006, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass (Wiley).

3. Goleman, D.,

Social Intelligence: The New Science of Human Relationships

. 2006: Bantam Dell (Random House).

4. Goleman, D. and R. Boyatzis, “Social intelligence and the biology of leadership.”

Harv Bus Rev

, 2008. 86(9): p. 74–81, 136.

5. Howe, N. and W. Strauss, “The next 20 years: how customer and workforce attitudes will evolve.”

Harv Bus Rev

, 2007. 85(7–8): p. 41–52, 191.

6. Weiss, J. and J. Hughes, “Want collaboration? Accept—and actively manage—conflict.”

Harv Bus Rev

, 2005. 83(3): p. 92–101, 149.

7. Katzenbach, J.R. and D.K. Smith, “The discipline of teams.”

Harv Bus Rev

, 1993. 71(2): p. 111–20.

8. Burciu, A. and C.V. Hapenciuc, “Non-Rational Thinking in the Decision Making Process.” Proceedings of the European Conference on Intellectual Capital, 2010: p. 152–160.

9. Clarke, N., “The impact of a training programme designed to target the emotional intelligence abilities of project managers.”

International Journal of Project Management

, 2010. 28(5): p. 461–468.

10. Ochieng, E.G. and A.D.F. Price, “Managing cross-cultural communication in multicultural construction project teams: The case of Kenya and UK.”

International Journal of Project Management

, 2010. 28(5): p. 449–460.

11. Taute, H.A., B.A. Huhmann, and R. Thakur, “Emotional Information Management: Concept development and measurement in public service announcements.”

Psychology & Marketing

, 2010. 27(5): p. 417–444.

12. Clarke, N., “Emotional intelligence and its relationship to transformational leadership and key project manager competences.”

Project Management Journal

, 2010. 41(2): p. 5–20.

13. Sadek, D.M., et al., “Service Quality Perceptions between Cooperative and Islamic Banks of Britain.”

American Journal of Economics & Business Administration

, 2010. 2(1): p. 1–5.

14. Gazzola, V., L. Aziz-Zadeh, and C. Keysers, “Empathy and the somatotopic auditory mirror system in humans.”

Curr Biol

, 2006. 16(18): p. 1824–9.

15. Chartrand, T.L. and J.A. Bargh, “The chameleon effect: the perception-behavior link and social interaction.”

J Pers Soc Psychol

, 1999. 76(6): p. 893–910.

16. Spengler, S., D.Y. von Cramon, and M. Brass, “Control of shared representations relies on key processes involved in mental state attribution.”

Hum Brain Mapp

, 2009.

17. Frith, C.D., “The social brain?”

Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci

, 2007. 362(1480): p. 671–8.

18. Iacoboni, M., et al., “Grasping the intentions of others with one’s own mirror neuron system.”

PLoS Biol

, 2005. 3(3): p. e79.

19. Noordzij, M.L., et al., “Brain mechanisms underlying human communication.”

Front Hum Neurosci

, 2009. 3: p. 14.

20. Gallese, V., “Before and below ‘theory of mind’: embodied simulation and the neural correlates of social cognition.”

Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci

, 2007. 362(1480): p. 659–69.

21. Gallese, V. and A. Goldman, “Mirror neurons and the simulation theory of mind-reading.”

Trends Cogn Sci

, 1998. 2(2): p. 493–501.

22. Kaplan, J.T. and M. Iacoboni, “Getting a grip on other minds: mirror neurons, intention understanding, and cognitive empathy.”

Soc Neurosci

, 2006. 1(3–4): p. 175–83.

23. Bastiaansen, J.A., M. Thioux, and C. Keysers, “Evidence for mirror systems in emotions.”

Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci

, 2009. 364(1528): p. 2391–404.

24. Cacioppo, J.T., et al., “In the eye of the beholder: individual differences in perceived social isolation predict regional brain activation to social stimuli.”

J Cogn Neurosci

, 2009. 21(1): p. 83–92.

25. Van Overwalle, F., “Social cognition and the brain: a meta-analysis.”

Hum Brain Mapp

, 2009. 30(3): p. 829–58.

26. Van Overwalle, F. and K. Baetens, “Understanding others’ actions and goals by mirror and mentalizing systems: a meta-analysis.”

Neuroimage

, 2009. 48(3): p. 564–84.

27. Kumar, S.A., et al., “Influence of Service Quality on Attitudinal Loyalty in Private Retail Banking: An Empirical Study.”

IUP Journal of Management Research

, 2010. 9(4): p. 21–38.

28. Galinsky, A.D., et al., “Why it pays to get inside the head of your opponent: the differential effects of perspective taking and empathy in negotiations.”

Psychol Sci

, 2008. 19(4): p. 378–84.

29. Li, W. and S. Han, “Perspective taking modulates event-related potentials to perceived pain.”

Neurosci Lett

, 2009.

30. Dosch, M., et al., “Learning to appreciate others: Neural development of cognitive perspective taking.”

Neuroimage

, 2009.

31. Shamay-Tsoory, S.G., J. Aharon-Peretz, and D. Perry, “Two systems for empathy: a double dissociation between emotional and cognitive empathy in inferior frontal gyrus versus ventromedial prefrontal lesions.”

Brain

, 2009. 132(Pt 3): p. 617–27.

32. Montag, C., et al., “Prefrontal cortex glutamate correlates with mental perspective-taking.”

PLoS One

, 2008. 3(12): p. e3890.

33. Tabibnia, G. and M.D. Lieberman, “Fairness and cooperation are rewarding: evidence from social cognitive neuroscience.”

Ann N Y Acad Sci

, 2007. 1118: p. 90–101.

34. Chiao, J.Y., et al., “Neural representations of social status hierarchy in human inferior parietal cortex.”

Neuropsychologia

, 2009. 47(2): p. 354–63.

35. Hsu, M., C. Anen, and S.R. Quartz, “The right and the good: distributive justice and neural encoding of equity and efficiency.”

Science

, 2008. 320(5879): p. 1092–5.

36. Sanfey, A.G., et al., “The neural basis of economic decision-making in the Ultimatum Game.”

Science

, 2003. 300(5626): p. 1755–8.

37. Olsson, A. and K.N. Ochsner, “The role of social cognition in emotion.”

Trends Cogn Sci

, 2008. 12(2): p. 65–71.

38. Hein, G. and T. Singer, “I feel how you feel but not always: the empathic brain and its modulation.”

Curr Opin Neurobiol

, 2008. 18(2): p. 153–8.

39. Tabibnia, G., A.B. Satpute, and M.D. Lieberman, “The sunny side of fairness: preference for fairness activates reward circuitry (and disregarding unfairness activates self-control circuitry).”

Psychol Sci

, 2008. 19(4): p. 339–47.