Your Brain and Business: The Neuroscience of Great Leaders (15 page)

Read Your Brain and Business: The Neuroscience of Great Leaders Online

Authors: Srinivasan S. Pillay

40. Rilling, J.K., et al., “The neural correlates of the affective response to unreciprocated cooperation.”

Neuropsychologia

, 2008. 46(5): p. 1256–66.

41. Hamel, G., “Strategy as revolution.”

Harv Bus Rev

, 1996. 74(4): p. 69–82.

42. Hassan, F., “Leading change from the top line.” Interview by Thomas A Stewart and David Champion.

Harv Bus Rev

, 2006. 84(7–8): p. 90–7, 188.

43. Luria, G., “The social aspects of safety management: Trust and safety climate.”

Accident Analysis & Prevention

, 2010. 42(4): p. 1288–1295.

44. Bstieler, L. and M. Hemmert, “Trust formation in Korean new product alliances: How important are pre-existing social ties?”

Asia Pacific Journal of Management

, 2010. 27(2): p. 299–319.

45. Tanghe, J., B. Wisse, and H. van der Flier, “The Role of Group Member Affect in the Relationship between Trust and Cooperation.”

British Journal of Management

, 2010. 21(2): p. 359–374.

46. Fink, M. and A. Kessler, “Cooperation, Trust and Performance—Empirical Results from Three Countries.”

British Journal of Management

, 2010. 21(2): p. 469–483.

47. Edwards, J.R. and D.M. Cable, “The value of value congruence.”

J Appl Psychol

, 2009. 94(3): p. 654–77.

48. Boudreau, C., M.D. McCubbins, and S. Coulson, “Knowing when to trust others: an ERP study of decision making after receiving information from unknown people.”

Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci

, 2009. 4(1): p. 23–34.

49. Kramer, R.M., “Rethinking trust.”

Harv Bus Rev

, 2009. 87(6): p. 68–77, 113.

50. Khurana, R. and N. Nohria, “It’s time to make management a true profession.”

Harv Bus Rev

, 2008. 86(10): p. 70–7, 140.

51. Hurley, R.F., “The decision to trust.”

Harv Bus Rev

, 2006. 84(9): p. 55–62, 156.

52. Maratos, F.A., et al., “Coarse threat images reveal theta oscillations in the amygdala: a magnetoencephalography study.”

Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci

, 2009. 9(2): p. 133–43.

53. Seres, I., Z. Unoka, and S. Keri, “The broken trust and cooperation in borderline personality disorder.”

Neuroreport

, 2009. 20(4): p. 388–92.

54. Said, C.P., S.G. Baron, and A. Todorov, “Nonlinear amygdala response to face trustworthiness: contributions of high and low spatial frequency information.”

J Cogn Neurosci

, 2009. 21(3): p. 519–28.

55. Brown, D., D. Rose, and E. Lyons, “Self-generated expressions of residual complaints following brain injury.”

NeuroRehabilitation

, 2009. 24(2): p. 175–83.

56. Pessiglione, M., et al., “Subliminal instrumental conditioning demonstrated in the human brain.”

Neuron

, 2008. 59(4): p. 561–7.

57. Baumgartner, T., et al., “Oxytocin shapes the neural circuitry of trust and trust adaptation in humans.”

Neuron

, 2008. 58(4): p. 639–50.

58. Krueger, F., et al., “Neural correlates of trust.”

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A

, 2007. 104(50): p. 20084–9.

59. van den Bos, W., et al., “What motivates repayment? Neural correlates of reciprocity in the Trust Game.”

Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci

, 2009. 4(3): p. 294–304.

60. Krajbich, I., et al., “Economic games quantify diminished sense of guilt in patients with damage to the prefrontal cortex.”

J Neurosci

, 2009. 29(7): p. 2188–92.

61. Mobbs, D., et al., “A key role for similarity in vicarious reward.”

Science

, 2009. 324(5929): p. 900.

62. Krill, A. and S.M. Platek, “In-group and out-group membership mediates anterior cingulate activation to social exclusion.”

Front Evol Neurosci

, 2009. 1: p. 1.

63. Karelina, K., et al., “Social isolation alters neuroinflammatory response to stroke.”

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A

, 2009. 106(14): p. 5895–900.

64. Cao, Z., et al., “Anterior cingulate cortex modulates visceral pain as measured by visceromotor responses in viscerally hypersensitive rats.”

Gastroenterology

, 2008. 134(2): p. 535–43.

65. Schwabe, L. and O.T. Wolf, “Stress prompts habit behavior in humans.”

J Neurosci

, 2009. 29(22): p. 7191–8.

66. Bowles, D.P. and B. Meyer, “Attachment priming and avoidant personality features as predictors of social-evaluation biases.”

J Pers Disord

, 2008. 22(1): p. 72–88.

67. Masten, C.L., et al., “Neural correlates of social exclusion during adolescence: understanding the distress of peer rejection.”

Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci

, 2009. 4(2): p. 143–57.

68. Eisenberger, N.I., M.D. Lieberman, and K.D. Williams, “Does rejection hurt? An FMRI study of social exclusion.”

Science

, 2003. 302(5643): p. 290–2.

69. Hamel, G., “Moon shots for management.”

Harv Bus Rev

, 2009. 87(2): p. 91–8.

70. Falk, E.B., et al., “The Neural Correlates of Persuasion: A Common Network across Cultures and Media.”

J Cogn Neurosci

, 2009.

71. Adams, D.M., “Ethics consultation and ‘facilitated’ consensus.”

J Clin Ethics

, 2009. 20(1): p. 44–55.

72. Klucharev, V., et al., “Reinforcement learning signal predicts social conformity.”

Neuron

, 2009. 61(1): p. 140–51.

73. Campbell, A., J. Whitehead, and S. Finkelstein, “Why good leaders make bad decisions.”

Harv Bus Rev

, 2009. 87(2): p. 60–6, 109.

74. Le Ber, M.J. and O. Branzei, “(Re)Forming Strategic Cross-Sector Partnerships: Relational Processes of Social Innovation.”

Business & Society

, 2010. 49(1): p. 140–172.

75. Belk, R., Sharing.

Journal of Consumer Research

, 2010. 36(5): p. 715–734.

76. Mallin, M.L., E. O’Donnell, and M.Y. Hu, “The role of uncertainty and sales control in the development of sales manager trust.”

Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing

, 2010. 25(1): p. 30–42.

77. Popper, M. and K. Amit, “Influence of attachment style on major psychological capacities to lead.”

J Genet Psychol

, 2009. 170(3): p. 244–67.

78. Davidovitz, R., et al., “Leaders as attachment figures: leaders’ attachment orientations predict leadership-related mental representations and followers’ performance and mental health.”

J Pers Soc Psychol

, 2007. 93(4): p. 632–50.

79. Bresnahan, C.G. and Mitroff, II, “Leadership and attachment theory.”

Am Psychol

, 2007. 62(6): p. 607–8.

80. Mayseless, O. and M. Popper, “Reliance on leaders and social institutions: an attachment perspective.”

Attach Hum Dev

, 2007. 9(1): p. 73–93.

81. Berson, Y., O. Dan, and F.J. Yammarino, “Attachment style and individual differences in leadership perceptions and emergence.”

J Soc Psychol

, 2006. 146(2): p. 165–82.

82. Quirin, M., J.C. Pruessner, and J. Kuhl, “HPA system regulation and adult attachment anxiety: individual differences in reactive and awakening cortisol.”

Psychoneuroendocrinology

, 2008. 33(5): p. 581–90.

83. Suslow, T., et al., “Attachment avoidance modulates neural response to masked facial emotion.”

Hum Brain Mapp

, 2009. 30(11): p. 3553–62.

84. Vrticka, P., et al., “Individual attachment style modulates human amygdala and striatum activation during social appraisal.”

PLoS One

, 2008. 3(8): p. e2868.

Chapter 4. Of Innovation, Intuition, and Impostors: Intangible Vulnerabilities in the Brains of Great Leaders

Certain characteristics always surround a great leader: innovation, persuasion, resilience, intuition, and inspiration being a few of these. However, not all leaders who become great leaders can stay there, and not all leaders who could become great leaders actually get there. What are the reasons that leaders may fall short of their visionary capacities, and how can we understand this through the neural lens?

Although the literature is full of information about variables we can operationalize, little is said about things that are more intangible. Furthermore, leaders often struggle with this themselves, especially when they have to think of what they have been doing automatically. It often throws them into a frenzy of anxiety. It is like asking them while they are driving on a major highway at 75 mph to stop because you need to find the money you just dropped.

For great leaders, then, the challenges are often different. They do not need more techniques telling them how to be analytical. They often do not need coaching processes that tell them that they need to benchmark their goals or that they need to listen more or develop a set of basic skills. Instead, these leaders need to understand things that feel somewhat mysterious to them.

For example, why, after a history of repeated successes, do they feel as though they are failing? Why has the thrill gone out of the job? Is intuition real or is it just a state of imagined knowledge? What constitutes expert performance? What does it mean to be an innovator? These and other questions are some of the ones that will be addressed in this chapter.

The Neuroscience of Innovation

The concept:

In a recent article titled “The Innovator’s DNA,” Jeffrey Dyer and colleagues

1

outlined five discovery skills that distinguish the most creative executives: associating, questioning, observing, experimenting, and networking. These characteristics help these executives form connections, break out of the status quo, gain insights, try out new experiences, and hear radical ideas from diverse individuals with different backgrounds. For example, having the “right” market vision prior to new product development in uncertain situations may increase competitive advantage

2

and may require more than simple analysis—it may require a creative vision.

In addition, “unleash[ing] creativity” in followers

3

is critical to effective leadership. In his article “Moon Shots for Management,” Gary Hamel describes four basic processes that stimulate management innovation: “a big problem that demands fresh thinking, creative principles or paradigms that can reveal new approaches, an evaluation of the conventions that constrain novel thinking, and examples and analogies that help redefine what can be done.”

3

In fact, management innovation is critical when it comes to leveraging competitive advantage as well.

4

Given that innovation is so important to companies then, how can we understand this in terms of the neuroscience?

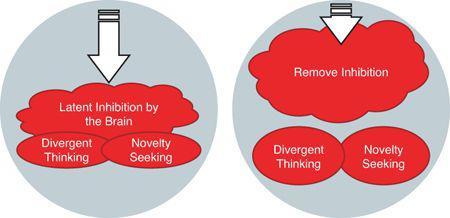

In the neuroscience literature, creativity is said to involve four processes: preparation, incubation, illumination, and verification—not unlike the intrauterine development of a fetus. Fostering these capacities requires an understanding of divergent thinking, novelty

seeking, and suppression of latent inhibition.

5

(We sometimes inhibit our most creative thoughts because we cannot immediately justify them.) This requires the frontal cortex to be less inhibited than it usually is (some may say even slightly dysfunctional) to allow for the flow of creative thoughts and problem solving. Apart from this frontal “release,” creative people also have a high degree of connectivity that joins even seemingly disparate brain regions in the thinking process, thereby creating new connections as well.

Figure 4.1

summarizes some of these processes.

Figure 4.1. The relationship between inhibition and creative processes

So why don’t we just continue being creative? If it is as easy as “disinhibition,” why not just do it? According to Ambar Chakravarty, one of the major implied threats is that the “payoff” occurs on an inverted U graph. Some disinhibition but not total disinhibition is helpful. Some divergent thinking but not the tangentiality of mania is needed. Thus, innovation and creativity require risk management—and it is fear of “madness” that often stands as a stalwart enemy of creativity because this attitude prevents creativity. Hence, the frontal cortex is engaged to prevent the crisis on the “downside” of the U. To help manage this curve, external resources (e.g., consultants) need to work with the innovation mentality of internal resources within the company to help execute new innovations.

6