Your Brain and Business: The Neuroscience of Great Leaders (19 page)

Read Your Brain and Business: The Neuroscience of Great Leaders Online

Authors: Srinivasan S. Pillay

The application:

For enhancing expert performance, the following brain-based principles may be used: (1) Keeping cool when it is needed

requires extensive practice to “train” the brain to focus attention. (2) Although emotions are necessary for making decisions, just before action, focus is critical. Experts have already filtered out all emotion while about to perform their tasks. (3) Experts rely on creative aspects of their brains to perform expertly—keeping thought processes or even interventions linear will not take advantage of developed expertise. (4) Gut-instinct centers are active in the expert brain during practice. Therefore, during the coaching session, keep yourself open to all the information your brain and body provide to you. (5) It is clear that a staged approach to problem solving may not be the only way to solve problems. Coaching may sometimes be at odds with this. Coaches working with leaders may find that a greater flexibility is needed on the part of the coach to stimulate intuitive problem solving. Asking an expert leader to use a staged approach is like asking an expert pianist to “think” about what he or she is playing. The feeling of the musicality is lost.

The Neuroscience of Advice-Giving

The concept:

Leaders are often in the position of developing other leaders. In the course of doing this, they are in the position to give advice. Advice, although it demonstrates the competency in the leader, may in fact restrict and not share that competency, according to a recent brain imaging study.

70

This is because brain imaging shows that when advice is given, it “offloads” the value of decision options from the listener’s brain (intraparietal sulcus, posterior cingulate cortex, cuneus, precuneus, inferior frontal gyrus, and middle temporal gyrus) so that there are no correlations between brain activation and attributed value when advice is given, as compared to when it is not given. Furthermore, “probability weighting” brain regions (anterior cingulate cortex, dorsolateral PFC, thalamus, medial occipital gyrus, and anterior insula) activated more flatly when advice was given compared to when it was not.

The application:

One of the reasons it may not be useful to give advice is that this turns off probability weighting and value attribution (essentially effective decision making) in the brain of the follower.

That is, advice turns the brain of the listener “off.” This can be very important to reflect on when leaders micromanage or are convinced of their own experience and thus want to give advice. Mentioning this brain imaging work may help put this advice into perspective.

Once again, we are still learning what these brain findings mean, and as our knowledge increases, even more subtle levels of application may become possible.

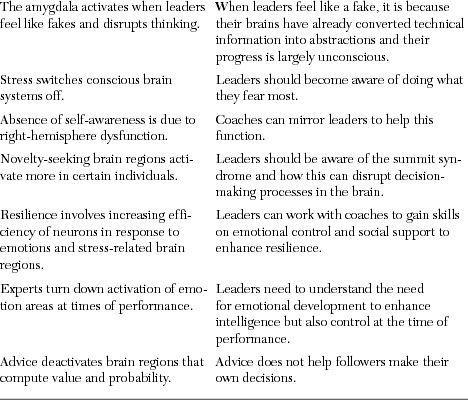

Table 4.2

illustrates how brain science can facilitate coaching intangible vulnerabilities of leaders.

Table 4.2. Coaching Interventions on Leadership Intangibles

Conclusion

Intangible vulnerabilities register in specific ways in the brain. By understanding this and using the brain findings as targets, leaders and managers can improve their performance.

References

1. Dyer, J.H., H.B. Gregersen, and C.M. Christensen, “The Innovator’s DNA.”

Harv Bus Rev

, 2009. 87(12): p. 60–7, 128.

2. Reid, S.E. and U. de Brentani, “Market Vision and Market Visioning Competence: Impact on Early Performance for Radically New, High-Tech Products.”

Journal of Product Innovation Management

, 2010. 27(4): p. 500–518.

3. Hamel, G., “Moon shots for management.”

Harv Bus Rev

, 2009. 87(2): p. 91–8.

4. Feigenbaum, A.V. and D.S. Feigenbaum, “What quality means today.”

Sloan Manage Rev

, 2005. 46(2): p. 96.

5. Chakravarty, A., “The creative brain—Revisiting concepts.”

Med Hypotheses

, 2009.

6. Mol, M.J. and J. Birkinshaw, “The sources of management: when firms introduce new management practices.”

Journal of Business Research

, Forthcoming.

7. Green, A.E., et al., “Connecting long distance: semantic distance in analogical reasoning modulates frontopolar cortex activity.”

Cereb Cortex

. 20(1): p. 70–6.

8. Bischof, M. and C.L. Bassetti, “Total dream loss: a distinct neuropsychological dysfunction after bilateral PCA stroke.”

Ann Neurol

, 2004. 56(4): p. 583–6.

9. Burke, K.A., et al., “Orbitofrontal inactivation impairs reversal of Pavlovian learning by interfering with ‘disinhibition’ of responding for previously unrewarded cues.”

Eur J Neurosci

, 2009.

10. Starkstein, S.E. and R.G. Robinson, “Mechanism of disinhibition after brain lesions.”

J Nerv Ment Dis

, 1997. 185(2): p. 108–14.

11. Hirono, N., et al., “Hypofunction in the posterior cingulate gyrus correlates with disorientation for time and place in Alzheimer’s disease.”

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry

, 1998. 64(4): p. 552–4.

12. Amorapanth, P.X., P. Widick, and A. Chatterjee, “The Neural Basis for Spatial Relations.”

J Cogn Neurosci

, 2009.

13. Jung, R.E., et al., “Neuroanatomy of creativity.”

Hum Brain Mapp

, 2009.

14. Oberman, L.M. and V.S. Ramachandran, “Preliminary evidence for deficits in multisensory integration in autism spectrum disorders: the mirror neuron hypothesis.”

Soc Neurosci

, 2008. 3(3–4): p. 348–55.

15. Moore, D.W., et al., “Hemispheric connectivity and the visual-spatial divergent-thinking component of creativity.”

Brain Cogn

, 2009. 70(3): p. 267–72.

16. Fink, A., B. Graif, and A.C. Neubauer, “Brain correlates underlying creative thinking: EEG alpha activity in professional vs. novice dancers.”

Neuroimage

, 2009. 46(3): p. 854–62.

17. Zakharchenko, D.V. and N.E. Sviderskaia, [EEG correlates for efficiency of the nonverbal creative performance (drawing)].

Zh Vyssh Nerv Deiat Im I P Pavlova

, 2008. 58(4): p. 432–42.

18. Gibson, C., B.S. Folley, and S. Park, “Enhanced divergent thinking and creativity in musicians: a behavioral and near-infrared spectroscopy study.”

Brain Cogn

, 2009. 69(1): p. 162–9.

19. Kowatari, Y., et al., “Neural networks involved in artistic creativity.”

Hum Brain Mapp

, 2009. 30(5): p. 1678–90.

20. Dietrich, A., “Neurocognitive mechanisms underlying the experience of flow.”

Conscious Cogn

, 2004. 13(4): p. 746–61.

21. Chavez-Eakle, R.A., et al., “Cerebral blood flow associated with creative performance: a comparative study.”

Neuroimage

, 2007. 38(3): p. 519–28.

22. Razumnikova, O.M., “Creativity related cortex activity in the remote associates task.”

Brain Res Bull

, 2007. 73(1–3): p. 96–102.

23. Gos, T., et al., “Suicide and depression in the quantitative analysis of glutamic acid decarboxylase—Immunoreactive neuropil.”

J Affect Disord

, 2009. 113(1–2): p. 45–55.

24. Stanfield, A.C., et al., “Structural abnormalities of ventrolateral and orbitofrontal cortex in patients with familial bipolar disorder.”

Bipolar Disord

, 2009. 11(2): p. 135–44.

25. Bodis-Wollner, I., “Pre-emptive perception.”

Perception

, 2008. 37(3): p. 462–78.

26. Gee, A.L., et al., “Neural enhancement and pre-emptive perception: the genesis of attention and the attentional maintenance of the cortical salience map.”

Perception

, 2008. 37(3): p. 389–400.

27. McKyton, A., Y. Pertzov, and E. Zohary, “Pattern matching is assessed in retinotopic coordinates.”

J Vis

, 2009. 9(13): p. 19 1–10.

28. Radin, D. and A. Borges, “Intuition through time: what does the seer see?”

Explore (NY)

, 2009. 5(4): p. 200–11.

29. Kuo, W.J., et al., “Intuition and deliberation: two systems for strategizing in the brain.”

Science

, 2009. 324(5926): p. 519–22.

30. Craig, A.D., “How do you feel—now? The anterior insula and human awareness.”

Nat Rev Neurosci

, 2009. 10(1): p. 59–70.

31. Volz, K.G., R. Rubsamen, and D.Y. von Cramon, “Cortical regions activated by the subjective sense of perceptual coherence of environmental sounds: a proposal for a neuroscience of intuition.”

Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci

, 2008. 8(3): p. 318–28.

32. Segalowitz, S.J., “Knowing before we know: conscious versus preconscious top-down processing and a neuroscience of intuition.”

Brain Cogn

, 2007. 65(2): p. 143–4.

33. Volz, K.G. and D.Y. von Cramon, “What neuroscience can tell about intuitive processes in the context of perceptual discovery.”

J Cogn Neurosci

, 2006. 18(12): p. 2077–87.

34. Ilg, R., et al., “Neural processes underlying intuitive coherence judgments as revealed by fMRI on a semantic judgment task.”

Neuroimage

, 2007. 38(1): p. 228–38.

35. Murray, G.K., et al., “Substantia nigra/ventral tegmental reward prediction error disruption in psychosis.”

Mol Psychiatry

, 2008. 13(3): p. 239, 267–76.

36. Simon, M., et al., [Mirror neurons—novel data on the neurobiology of intersubjectivity].

Psychiatr Hung

, 2007. 22(6): p. 418–29.

37. Vivona, J.M., “Leaping from brain to mind: a critique of mirror neuron explanations of countertransference.”

J Am Psychoanal Assoc

, 2009. 57(3): p. 525–50.

38. Thomas, L.E. and A. Lleras, “Swinging into thought: directed movement guides insight in problem solving.”

Psychon Bull Rev

, 2009. 16(4): p. 719–23.

39. Gallese, V., “Motor abstraction: a neuroscientific account of how action goals and intentions are mapped and understood.”

Psychol Res

, 2009. 73(4): p. 486–98.

40. Thomas, L.E. and A. Lleras, “Covert shifts of attention function as an implicit aid to insight.”

Cognition

, 2009. 111(2): p. 168–74.

41. de Vries, M.F., “The dangers of feeling like a fake.”

Harv Bus Rev

, 2005. 83(9): p. 108–16, 159.

42. Wegner, D.M., “How to think, say, or do precisely the worst thing for any occasion.”

Science

, 2009. 325(5936): p. 48–50.

43. Morin, C., [Sense of personal identity and focal brain lesions].

Psychol Neuropsychiatr Vieil

, 2009. 7(1): p. 21–9.

44. Breen, N., D. Caine, and M. Coltheart, “Mirrored-self misidentification: two cases of focal onset dementia.”

Neurocase

, 2001. 7(3): p. 239–54.

45. Parsons, G.D. and R.T. Pascale, “Crisis at the summit.”

Harv Bus Rev

, 2007. 85(3): p. 80–9, 142.

46. Jiang, Y., et al., “Brain responses to repeated visual experience among low and high sensation seekers: role of boredom susceptibility.”

Psychiatry Res

, 2009. 173(2): p. 100–6.

47. Aslanyan, E.V. and V.N. Kiroy, “Electroencephalographic evidence on the strategies of adaptation to the factors of monotony.”

Span J Psychol

, 2009. 12(1): p. 32–45.