Your Brain and Business: The Neuroscience of Great Leaders (21 page)

Read Your Brain and Business: The Neuroscience of Great Leaders Online

Authors: Srinivasan S. Pillay

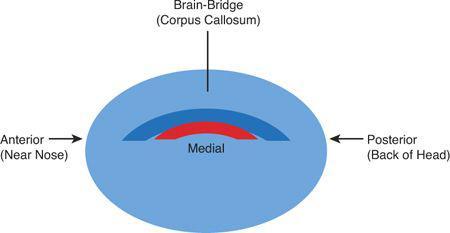

Figure 5.6. Position of the brain-bridge

Thus, when we’re thinking of action and the changes necessary for action to occur in the brain, we need to study the connections in the “change circuit,” which is shown in

Figure 5.7

.

Figure 5.7. Summary of functional inputs to the accountant

The application:

Most people recognize that for change to occur, they have to think about a situation. But many people also leave out the feeling or emotion when they are trying to change. If they do this, the brain’s accountant is missing vital information. When there is resistance to change, it is very rarely a missing thought process. Most often, it is a missing emotion. Coaches or managers can say to leaders, “When you are trying to make a change, your brain has to assess the pros and cons of your decision. Before you act, the accountant in your brain does a quick calculation, but it relies on more than just your rational thinking to do this. It also relies on your emotions. How would you feel if you were to make this change?” This will allow leaders to add the emotional component to their analysis more readily and will move them closer to change.

Biased Choice Value

The concept:

Another reason that change is difficult is that we tend to increase the value of our choices after we make them. A recent study has shown that this change in preference (that is, preferring our choices more after we make them than before) is registered

by the brain’s reward system (caudate nucleus, part of the basal ganglia). In other words, after a choice is made, the difference in activation in the reward system for selected versus rejected choices is much greater.

4

The application:

We often think that we have to first develop complete commitment to a choice before we make a decision, but research shows us that we develop increased commitment to our choices after we make a decision. We can apply this to coaching in the following ways:

• Use this information to handle a difficult conversation that involves overvaluing a choice that has been made in the past. For example, a team member may not want to change a way of doing things and rationalize previous methods. Instead of using judgmental language about overvaluing, you can talk about how the brain processes preference after choice and what the specific challenges are.

• Use this information to encourage a team member to make multiple small decisions on the way to a big decision, because each step of the way, the chosen path will increase the commitment to that decision. Oftentimes, making a big leap is very difficult for most people, and many people postpone change due to this. It takes a long time to develop commitment to a large change in your life. However, by making small decisions, you can help yourself because each decision increases commitment (and reward center activation).

• Use this information to help a team member understand why “imagining” being committed to a choice is not the reality of what will happen after a choice is made. It can be helpful to explain to someone who is avoiding commitment that the missing element may be a “real” decision. One way to allay fears of the unknown (e.g., pursuing an innovative strategy) is to recognize that when we make a choice without knowing, we increase our commitment to that choice.

Managers and coaches can tell team members the following: “We only move ourselves to action when the brain feels that the rewards of the action outweigh the losses. Before we make a decision about a

choice we desire, the reward system must activate enough to tell the action centers of our brains that we need to act. However, if we are stuck in old patterns of behavior, it is because the brain’s reward system activates more after we have made our choices. To move to a new choice requires overcoming this excessive reward signal in the brain.”

In addition, for the opposite situation the following is true: “The brain has difficulty handling loads of emotional information. When we have a challenging emotional task, the brain will shut down. We may start out in the new direction, but it is difficult to remain committed. One way to increase the chances of commitment to a new goal is to make small decisions along the way. These decisions could be a decision to move or a decision to rest. Every time you make such a decision, you reward the brain and its signal becomes even stronger, propelling you in the direction of the desired change.”

So, when we choose something, our brains tend to want us to remain committed to it, and even if we have an inkling that our new decision is not “right” in some way, to truly overcome this automatic bias, the brain has to deliberately examine what it is overlooking. This is also called the “honeymoon-hangover effect.” In this effect, low satisfaction would precede a voluntary job change, with an increase in job satisfaction immediately following a job change (the honeymoon effect), followed eventually by a decline in job satisfaction (the hangover effect).

5

When change is intended or real, it is easier to overcome the hangover effect.

Conditioning

The concept:

The third reason that change is difficult involves a phenomenon called “conditioning.” Conditioning refers to an automatic process that has been set up in the brain in response to a stimulus. In the business environment, a question such as “Why don’t I change my job?” or a statement such as “I need to think about increasing my profits” may lead to habitual ways of thinking with no real change. The fundamental idea is that the human brain sets itself

into patterns of behavior once that behavior has been learned. We can think of conditioned behaviors as “habit memory systems.” (Recall that short-term memory is subserved by the DLPFC and long-term memory by the hippocampus.)

On account of these habit memory systems, we repeat patterns of behavior in our lives. These responses are very ingrained, and even after an initial change, people often revert to the old way of doing things. As a coach, this is critical to understand as you may see that a client has started to change, but you cannot assume that this will continue because conditioned brain circuits are very powerful.

Examples of conditioning in personal situations include the following: If a woman had an alcoholic father who abused her, every time her boyfriend drinks a few beers, she might develop the automatic internal expectation that she would be abused. If a man had a terrible first marriage, he might automatically expect that every subsequent marriage will be terrible. The human brain appears to remember “first” experiences and then recalls these experiences whenever there is a trigger. The brain goes back to old ways of acting when old triggers are present. Coaches can help their clients by aiding them to identify what their triggers are. The fact that these triggers are so powerful and sometimes transmitted in families makes people sometimes mistake them for genetic influences. People often think that they are “hardwired.” However, when we examine the concept of neuroplasticity (the brain’s ability to change) later on, we will see that this is in fact not the case.

Elise D. was an administrative assistant who had had a long history of working for doctors. However, she kept getting fired from her job when there were cutbacks. For the longest time, when I coached her, she believed that there were ethnic slants against her and that her Jewish bosses did not like her. So, whenever she applied for her next job, because there were many Jewish doctors in the town in which she was applying, she would find herself being overly cautious, making mistakes because of her nervousness, and eventually getting fired again. It was only when she confronted this “habit memory” that

she was able to change the mental framework to “I must make myself indispensable in a short period of time so that when there are cutbacks, I will be valued enough to stay on.”

What Is Happening in the Brain When Conditioning Occurs?

Long-term potentiation (LTP):

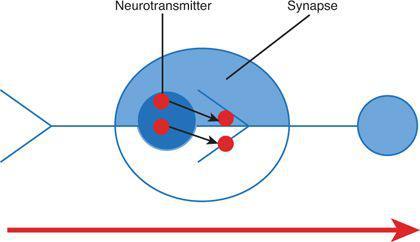

Nerve cells in the brain are called “neurons.” Between two neurons there are synapses. Neurotransmitters such as dopamine and serotonin are released from one nerve cell to attach to receptors on the other.

Figure 5.8

illustrates this.

Figure 5.8. Diagrammatic representation of a synapse

Long-term potentiation occurs when habits cause neurons to improve their connection by firing simultaneously. When the learning is productive, this is helpful. When the learning is destructive, this is harmful. When leaders are subjected to conditioned learning, they can become conditioned by associating a harmless stimulus with a harmful memory (like Elise) or they may become passive in response to the harm. The learning that occurs, occurs in the hippocampus. The hippocampus is the long-term memory store in the brain (see

Figure 5.9

).

Figure 5.9. Spatial relationship of amygdala and hippocampus

The application:

Managers, leaders, and coaches may encounter clients who have automatic responses to common situations. They may be in the habit of checking email every five minutes, or they may be in the habit of removing their emotions from equations that the brain’s accountant is figuring out. These habits of memory are stored in the hippocampus. If the manager or coach identifies that these habits are harmful, they may explain that habits come from brain circuits forming tight connections that have to be undone. The first step of identifying a need to change a habit is a great indication that that habit could change, but to truly change habits, we have to form new strong brain connections through new, powerful associations. Managers and coaches can communicate this by saying the following: “The patterns you are trying to change have been ingrained in you for a long time. That is because nerve cells in the brain form stronger and stronger connections as habits exist for longer. To break these patterns, we have to do more than just think of what we want. We have to do whatever we can to form new brain circuits that are stronger than the old ones. To do this, we must be motivated and also have an emotional connection with our new choices.”