Your Brain and Business: The Neuroscience of Great Leaders (25 page)

Read Your Brain and Business: The Neuroscience of Great Leaders Online

Authors: Srinivasan S. Pillay

Conclusion

It is not enough to have an idea; you have to bring yourself to action. The first step is to increase commitment to action, which requires activating the left frontal cortex through the mechanisms discussed in this chapter. Once this is done, the brain is ready to move from action orientation to action.

References

1. Gatenby, A. and M. Lees, “Leadership Coaching Tip: There is a mind-shift evolving.”

Integral Leadership Review

, 2010. 10(2): p. 1–2.

2. Hurwitz, M. and S. Hurwitz, “The romance of the follower: part 3.”

Industrial & Commercial Training

, 2009. 41(6): p. 326-333.

3. Hemp, P., “Death by information overload.”

Harv Bus Rev

, 2009. 87(9): p. 82–9, 121.

4. Sharot, T., B. De Martino, and R.J. Dolan, “How choice reveals and shapes expected hedonic outcome.”

J Neurosci

, 2009. 29(12): p. 3760–5.

5. Boswell, W.R., J.W. Boudreau, and J. Tichy, “The relationship between employee job change and job satisfaction: the honeymoon-hangover effect.”

J Appl Psychol

, 2005. 90(5): p. 882–92.

6. Abel, S., et al., “The separation of processing stages in a lexical interference fMRI-paradigm.”

Neuroimage

, 2009. 44(3): p. 1113–24.

7. Herry, C., et al., “Switching on and off fear by distinct neuronal circuits.”

Nature

, 2008. 454(7204): p. 600–6.

8. Alvarez, R.P., et al., “Contextual fear conditioning in humans: cortical-hippocampal and amygdala contributions.”

J Neurosci

, 2008. 28(24): p. 6211–9.

9. Izumi, T., et al., “Changes in amygdala neural activity that occur with the extinction of context-dependent conditioned fear stress.”

Pharmacol Biochem Behav

, 2008. 90(3): p. 297–304.

10. Zimmerman, J.M., et al., “The central nucleus of the amygdala is essential for acquiring and expressing conditional fear after overtraining.”

Learn Mem

, 2007. 14(9): p. 634–44.

11. Ponnusamy, R., A.M. Poulos, and M.S. Fanselow, “Amygdala-dependent and amygdala-independent pathways for contextual fear conditioning.”

Neuroscience

, 2007. 147(4): p. 919–27.

12. Westen, D., et al., “Neural bases of motivated reasoning: an FMRI study of emotional constraints on partisan political judgment in the 2004 U.S. Presidential election.”

J Cogn Neurosci

, 2006. 18(11): p. 1947–58.

13. Iverson, R.D. and P. Roy, “A Causal Model of Behavioral Commitment: Evidence From a Study of Australian Blue-collar Employees.”

Journal of Management

, 1994. 20(1): p. 15.

14. Pfeffer, J. and J. Lawler, “Effects of Job Alternatives, Extrinsic Rewards, and Behavioral Commitment on Attitude toward the Organization: A Field Test of the Insufficient Justification Paradigm.”

Administrative Science Quarterly

, 1980. 25(1): p. 38–56.

15. Benkhoff, B., “Catching up on competitors: how organizations can motivate employees to work harder.”

International Journal of Human Resource Management

, 1996. 7(3): p. 736–752.

16. Kim, S., “Behavioral Commitment Among the Automobile Workers in South Korea[sup1].”

Human Resource Management Review

, 1999. 9(4): p. 419.

17. Harmon-Jones, E., et al., “Left frontal cortical activation and spreading of alternatives: tests of the action-based model of dissonance.”

J Pers Soc Psychol

, 2008. 94(1): p. 1–15.

18. Resulaj, A., et al., “Changes of mind in decision-making.”

Nature

, 2009. 461(7261): p. 263–6.

19. Munzert, J., et al., “Neural activation in cognitive motor processes: comparing motor imagery and observation of gymnastic movements.”

Exp Brain Res

, 2008. 188(3): p. 437–44.

20. Schienle, A., et al., “Worry tendencies predict brain activation during aversive imagery.”

Neurosci Lett

, 2009. 461(3): p. 289–92.

21. Damasio, A.R.,

Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason and the Human Brain

. 1994, New York: Putman.

22. Clark, L., et al., “Differential effects of insular and ventromedial prefrontal cortex lesions on risky decision-making.”

Brain

, 2008. 131(Pt 5): p. 1311–22.

23. Lorey, B., et al., “The embodied nature of motor imagery: the influence of posture and perspective.”

Exp Brain Res

, 2009. 194(2): p. 233–43.

24. Holmes, E.A., A.E. Coughtrey, and A. Connor, “Looking at or through rose-tinted glasses? Imagery perspective and positive mood.”

Emotion

, 2008. 8(6): p. 875–9.

25. Hagni, K., et al., “Observing virtual arms that you imagine are yours increases the galvanic skin response to an unexpected threat.”

PLoS One

, 2008. 3(8): p. e3082.

26. Vasquez, N.A. and R. Buehler, “Seeing future success: does imagery perspective influence achievement motivation?”

Pers Soc Psychol Bull

, 2007. 33(10): p. 1392–405.

27. Jeannerod, M., “Neural simulation of action: a unifying mechanism for motor cognition.”

Neuroimage

, 2001. 14(1 Pt 2): p. S103–9.

28. Cappelletti, M., et al., “Processing nouns and verbs in the left frontal cortex: a transcranial magnetic stimulation study.”

J Cogn Neurosci

, 2008. 20(4): p. 707–20.

29. Berlingeri, M., et al., “Nouns and verbs in the brain: grammatical class and task specific effects as revealed by fMRI.”

Cogn Neuropsychol

, 2008. 25(4): p. 528–58.

30. Heiser, M., et al., “The essential role of Broca’s area in imitation.”

Eur J Neurosci

, 2003. 17(5): p. 1123-8.

31. Sarampalis, A., et al., “Objective measures of listening effort: Effects of background noise and noise reduction.”

J Speech Lang Hear Res

, 2009.

32. Knoch, D., P. Brugger, and M. Regard, “Suppressing versus releasing a habit: frequency-dependent effects of prefrontal transcranial magnetic stimulation.”

Cereb Cortex

, 2005. 15(7): p. 885–7.

33. Eisenstat, R.A., et al., “The uncompromising leader.”

Harv Bus Rev

, 2008. 86(7–8): p. 50–7, 157.

34. Spronk, D., et al., “Long-term effects of left frontal rTMS on EEG and ERPs in patients with depression.”

Clin EEG Neurosci

, 2008. 39(3): p. 118–24.

Chapter 6. From Action Orientation to Change: How Brain Science Can Bring Managers and Leaders from Action Orientation to Action

In the previous chapter, we looked at the neuroscience behind the challenges to action and how to get leaders to be oriented to action. In this chapter, we will take a look at how neuroscience can help you, as an organizational development consultant, manager, leader, or coach, to bring leaders to action. Much of measuring effectiveness hinges on this one element—action—and maintaining that action.

Our experience of our own action depends on the brain making connections between intentions, plans, and eventual action.

1

If there were no connection, we would be unable to associate planning with actions. As managers, leaders, or coaches, we are faced with the challenge of coaching change and transformation. This chapter presents a discussion of important elements of change.

Anyone who has been involved in addressing a stated need for change knows all too well that the intent to change and the reality of changing are very different things. For most people, familiarity is safe and change signifies danger. As a result, the process of inspiring, intending, promoting, and maintaining change can be a very difficult and time-consuming one.

Organizational Context for Change

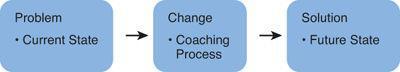

Change in organizations or individuals within that organization is usually introduced in the context of problem solving, as shown in

Figure 6.1

.

Figure 6.1. The place of change in decision-making

Thus, most people involved in executive development are called upon to facilitate change that will solve a problem. Change in an organization involves an alteration in the way we think in a manner that optimally benefits the individual, group, and organization. Change can occur at many levels, but to be truly effective, leaders wanting to institute fundamental change must often reflect change at all associated levels. If, for example, a company needs to change the way it thinks about increasing the market potential for a product, a change in the market segment must necessarily reflect a change in thinking at all levels, including but not limited to product marketing, distribution, and sales.

In business, change may involve mergers and acquisitions, privatization, or crises that require reorganization, such as downsizing or taking on different roles.

2

Also, with recent trends toward globalization and stiff competition, flexible, reconfigurable, and demand-driven production systems are vital, especially when the product life cycle is shorter and the market demand changes.

3

Managers are often left in the position to communicate with labor forces and are faced with the oftentimes difficult challenge of being change enablers.

4

Although superficial change is easiest (many unsuccessful efforts at strategic planning, for example, change the way things look without addressing more fundamental changes that need to occur), true, lasting, and impactful change has to occur at a much deeper level.

Model of the Relevance of Brain Science to Understanding Change

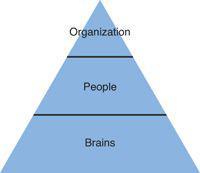

To understand the importance of neuroscience in organizational problem solving, we have only to reflect on the reality that organizations are made up of people who make decisions, and an important mediator of this decision making is the brain (see

Figure 6.2

). Although it is important to keep an open mind at all times, it is equally important to realize that change with regard to certain elements of organizations may be limited. Similarly, not all people are open to change, and not all parts of the brain or human psychology are susceptible to change.

Figure 6.2. Model of where brain science lies in organizations

Individual change precedes organizational change. Human capital is always at the basis of organizational change. And within human beings, the brain is at the crux of mediating change. Understanding how the brain mediates change could be tremendously helpful to us in understanding how we can institute the changes we want within an organization.

The premise in associating organizational change with neuroscience is that an organization is a living, breathing organism that is made up of living, breathing people and their machines. Recent research has therefore applied a cognitive neuroscience approach to reveal a deeper understanding of organizational processes.

5

,

6

Although

this knowledge is exciting and transformational itself, it is important to remember that this knowledge is also actively growing and subject to revision.

Relationship of the Neuron to Brain Change