Your Brain and Business: The Neuroscience of Great Leaders (23 page)

Read Your Brain and Business: The Neuroscience of Great Leaders Online

Authors: Srinivasan S. Pillay

As a coach, the type of change you are aiming for is one that is lasting, but also one that preserves the integrity of the client. And herein lies the challenge: How do you promote and coach change while preserving the integrity of the client? In other words, how do you not stretch the coil to complete flaccidity?

This brings us to the other important dimension of change, apart from the temporal one: namely, depth. In reworking this model, then, we can conceptualize change as shown in

Figure 5.12

.

Figure 5.12. The different dimensions of change

Coach mastery requires that the coach be fluent not just in superficial change, but change that occurs at a much deeper level. This type of change we refer to as

transformation.

Transformation is the hallmark of successful, measurable change and is a proven method that works in creating behavioral change. The beacon of transformation is

enrollment.

That is, in order to preserve the integrity of the client, the client has to enrolled in the agreed-upon agenda. The commitment has to be real.

Behavioral commitment in organizations relies on a number of factors, including attitudinal commitment.

13

In fact, when managers and leaders increase behavioral commitment in their team members, salary becomes less important with regard to job satisfaction,

14

and motivation to work harder increases.

15

Behavioral commitment involves positive and negative affectivity, role conflict and ambiguity, and autonomy and involvement. Each of these processes relates to how the brain manages commitment to a decision or organization.

16

The Neuroscience of Commitment

The concept:

Commitment is defined as “the act of binding yourself (intellectually or emotionally) to a course of action.” The necessity of commitment to change is based on the action-based model of dissonance, which predicts that following commitment to a decision involves a series of motivational factors that must arise to encourage approaching a desired goal in an effective and unconflicted way.

17

These approach-oriented processes as a state of mind are referred to as “action orientation.” For change to be successful, action orientation is essential. I call this the “get-set” position.

Imagine the beginning of a 100-meter sprint. All the runners are lined up. The starter cocks the gun and the runners look ahead: “On your mark, get set, go.” As a manager or coach, it is ideal to be able to engage the team members in their mission at this level of intensity.

Due to procrastination, many people will stay in the “on your mark” position and substitute this for action.

Two recent experiments have shown us what goes on in the brain when a person is committed to a decision. In Experiment 1, using neurofeedback, the application of an electrode to decrease left frontal cortical activation resulted in a decrease in commitment to a decision (see

Figure 5.13

).

Figure 5.13. Different views of the left frontal cortex

In Experiment 2, an increase in action orientation resulted in an increase in left frontal cortical activation and an increase in commitment to a decision. Thus, the left frontal cortex is critical in the commitment to a decision. It takes an action-oriented mindset to activate this region.

Thus, for change, you need commitment to the new action, which requires left frontal cortex activation.

The application:

There is a subtle difference between a plan and decision. Many people think that they can move from having a plan to action, but a decision is a commitment to a plan of action

18

and without this commitment lasting change is impossible. Effectively, a decision involves approach-oriented processes that have already been instituted.

When team members state that they have a plan, managers, leaders, and coaches can then inquire as to what approach behaviors they have instituted. One of the challenges of decision-making is that it takes the romance out of the plan or inspiration. Managers and coaches may want to think about each step of the action plan as one that generates the same mystique to keep team members faithful to the plan. Although theoretically, it also makes sense to just explain the explosion of this mystique, and accept it, my experience has been that it requires too much energy to move away from the inspiration and that each action-oriented step should generate the next level of mystique. For example, if you are a CEO, you might decide that the company needs a greater level of transparency to encourage a greater sense of trust. This idea is sound, but the notion of generating information for the company to look at can be daunting and discouraging. To maintain your commitment to this goal, you might decide to delegate this task to someone else. In this way, you do not have to deal with his or her own inertia. Managers and coaches can tell team members the following: “Your plan sounds great, and we have to decide how to get it in action. What are the first steps you would want to take to see your plan in action?” Then, you listen to the energy behind the articulated steps to discern whether this is in fact an action plan that has the momentum to reach completion. If it’s not, you can say, “We know from studies on brain biology that the left part of your frontal lobe has to be activated for action orientation to occur. It is like being in the ‘get set’ position before you can run a race. It adds momentum.”

Behavioral coaching has its precedent in sports coaching. It has long been known that part of the training for runners involves imagining the race. Champion runners are able to imagine running a race in the exact amount of time that they eventually run it. Imagination sets up the brain to perform an action. Coaching, therefore, ideally stimulates this focused imagination. Target goals stimulate the imagination, and benchmarking constitutes the racetrack—the start and end points of the race. When a runner reaches his or her destination, he or she knows it. The ideal result in coaching involves this quality of knowing.

Imagery vs. Observation

The concept:

The idea of imagery (i.e., creating mental images) is more complex than it might initially seem. If I asked a room full of people to imagine running a 100-meter race and then asked them what they were imagining, I would likely get a variety of responses. Some people would say that they saw themselves running; others would say that they saw themselves at the start line; still others would say that they imagined reaching their goal. There would also be those who say that they did not actually see a picture of themselves but instead put themselves on the track and felt others running around them. Each of these is an imagination, but each is different.

It turns out that imagining an action (motor imagery) and observing the action stimulate overlapping areas in the brain, but they are not identical.

19

An fMRI conjunction analysis (an analysis that looks at commonly overlapping areas for both conditions) revealed overlapping activation for imagery and observation in the primary motor cortex, premotor cortex, and supplementary motor area (all movement-related regions) as well as in the intraparietal sulcus, cerebellar hemispheres, and parts of the basal ganglia (the reward and movement-related regions). The hippocampus (long-term memory), the superior parietal lobe, and the cerebellar areas were differentially activated in the observation condition. It is unclear what each of these activations represents, but the point is that there is significant overlap.

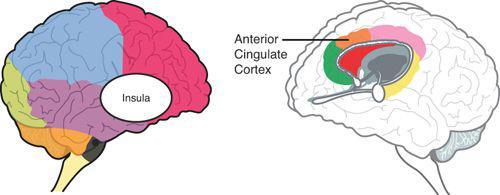

Note that motor imagery revealed stronger activation for imagery than observation in the posterior insula and the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC). (Recall that these brain regions—the gut feeling register and the conflict detector—are often activated together. These regions are shown in

Figure 5.14

.) It is also notable that when worry tendencies are high, ACC and insula activation are low,

20

probably because worry replaces internal gut-level conflict. It is no wonder, then, that worry disrupts image formation and that stress can inhibit your path to action. We also know that stress perpetuates habit. Thus,

asking team members to imagine what they want will be less than optimal if they are worried about the outcome.

Figure 5.14. Location of the insula and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC)

It is important to make sure that both of these brain regions are activated. Thus, asking a team member to imagine a desired behavior is critical if you want the posterior insula and ACC to activate. The insula has been implicated in mapping visceral states (gut feelings) associated with emotional states, giving rise to conscious emotions.

21

Thus, in imagery, we give the client a chance to convert unconscious feelings into more known conscious feelings that he or she will have more access to. The insula has also been implicated in the prediction of aversive or negative outcomes.

22

Therefore, it is essential that we involve this brain region in the action plan because it can signal real threats. Mounting an internal image with emotion calls the insula to action.

Note that imagining the spatial position of one’s own hand from the first-person perspective activates the left hemisphere motor and motor-related structures more than imagining in the third person. This occurs especially in the inferior parietal lobe. Also, imagining compatible actions from the first-person perspective activates the parietal lobe and insula much more than incompatible positions. That is, people have to be able to imagine the possibility of something as being real for this to stimulate the corresponding action.

23

Another study also showed that imagining positive descriptions of one’s self from the first-person perspective results in more positive

emotions than imagining one’s self through an observer’s eyes.

24

The same has been shown for negative emotions (which increase skin conductance, especially with first-person imagery).

25

However, a contrasting earlier study on imagery raises the question of whether this is always true. This study examined whether imagining future success can sometimes enhance people’s motivation to achieve it and found that students experience a greater increase in achievement motivation when they imagine their successful task completion from a third-person rather than a first-person perspective, in part because they conceive of this achievement abstractly.

26

It also reduces the pressure. Thus, both first- and third-person perspectives may be helpful, and using third-person perspectives initially may help people overcome the anxiety necessary to imagine in the first person.