Yours for Eternity: A Love Story on Death Row (32 page)

Read Yours for Eternity: A Love Story on Death Row Online

Authors: Damien Echols,Lorri Davis

Our core case support came from some of the most amazingly talented people living, and we have been honored to have their help and friendship. Eddie Vedder (Pearl Jam), Johnny Depp, Henry Rollins, Fran Walsh and Peter Jackson, Phillipa Boyens and Seth Miller, Margaret Cho, Natalie Maines, and Patti Smith. Then there were the hundreds of bands, artists, and writers who all contributed in countless ways.

And our legal team: amazing, amazing, amazing. Ed Mallett, thank you for your pro-bono efforts. Dennis Riordan, Don Horgan, Theresa Gibbons, and Deborah Sallings for taking on the case when it was code red and for bringing us back to life. Your briefs stunned the Arkansas Supreme Court into granting us the evidentiary hearing in 2010. The new guard who brought about the deal with the State of Arkansas that gained Damien’s release: Steve Braga and Patrick Benca, with the help of Lonnie Soury and Jay Salpeter. Our investigators, Ron Lax, and Rachael Geiser, thank you for everything. John Douglas and Steve Mark for thinking outside the box. I always consider Fran Walsh a part of the legal team. A big part.

The other investigation, our documentarians and their team: Amy Berg and your tireless crew, Holly Tunkel, you were all fearless.

Post-release brought about a whole new guard who were there to hold us up, keep us safe and dry, and enabled us to charter a new life together: Jill Vedder, Danny Forster, Susie Arons, Tahra Grant, Emily Lowe Mailaender, Kevin Wilson and Liz Henderson, Sherry and Sam Chico, Lucia Coale and Ed Schutte, Brian and Lauren Consolazio, Dr. Dan and his amazing staff—Alan Russo, Julie Marsibilio, and Judith Star. Our friend and mentor Ken Kamins.

Our dear friend Michele Anthony, thank you for feeding us, housing us, and your help in healing us. A very special thanks to Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky for making

Paradise Lost

.

To our amazing, amazing team at Blue Rider Press: Sarah Hochman, the best editor in the universe; Brian Ulicky, Aileen Boyle, and David Rosenthal—thank you for believing in our story. To our literary agent, Henry Dunow, and to our lawyer, Elliot Groffman, for your enormous generosity and big heart.

This book would not exist without Geoff Gray, who brought the idea of a story about letters to us in 2010, and Lindsey Stanberry, who transcribed thousands of our letters and gave us the loveliest of book titles. Thank you!

We suppose we’ve have left far too many people out, but we are so very grateful to everyone who was there for us. A shout-out to my sister Bunkey, and I want to send a special thank-you to my parents, Harry and Lynn Davis, for taking care of me, and for providing stability. Without that and God’s grace, we would not have endured.

Lorri and Damien

about the authors

Damien Echols and Lorri Davis met in 1996 and were married in a Buddhist ceremony at Tucker Maximum Security Unit in Tucker, Arkansas, in 1999. Born in 1974, Echols grew up in Mississippi, Tennessee, Maryland, Oregon, Texas, Louisiana, and Arkansas. At the age of eighteen, he was wrongfully convicted of murder, along with Jason Baldwin and Jessie Misskelley, Jr., thereafter known as the West Memphis Three. Echols received a death sentence and spent almost eighteen years on death row until he, Baldwin, and Misskelley were released in 2011. The WM3 have been the subject of

Paradise Lost

, a three-part documentary series produced by HBO, and

West of Memphis

, a documentary produced by Peter Jackson and Fran Walsh. Echols is the author of the

New York Times

best-selling memoir

Life After Death

(2012) and a self-published memoir,

Almost Home

(2005).

Lorri Davis was born and raised in West Virginia. A landscape architect by training, she worked in England and New York City until relocating to Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1998. For more than a decade, Davis spearheaded a full-time effort toward Echols’s release from prison, which encompassed all aspects of the legal case and forensic investigation. She was instrumental in raising funds for the defense and served as producer (with Echols) of

West of Memphis

. Echols and Davis live in New York City.

*

As Damien has explained elsewhere, he and I made “moonwater,” out of water we set out on the full moon and then drank at the same time every month. It was another way of being together while apart, knowing what the other was doing and that we were connecting.—LD

*

This was a Rule 37 hearing for Damien to be appointed a new counsel, ordered by a judge, as part of his appeal process; the Rule 37 is the procedure to prove that the original trial attorneys were ineffective, and that effective representation would have resulted in a different outcome. It was Damien’s first time outside of prison in three years—he was painful to look at, dressed in prison whites, hair unkempt, and shackles around his wrists, ankles, and waist. He was terribly thin.—LD

*

I set up a virtual phone at one point—there was a company that figured out that a local call from the prison had a surcharge and then a horrific minute-by-minute charge; there was no “local call.” So this company set up a local phone number for a customer to be forwarded from the prison—a middleman, essentially. I cut out the middleman, setting up a virtual local phone number in Tucker, Arkansas, so Damien would call, and the call would be forwarded to me, then my cell phone. Eventually the prison found out—I told a few other people about it, who had set up their own local numbers, too—and threatened to take my phone number off the list completely so Damien wouldn’t be able to call. At that point I had multiple numbers, so that if one was shut off, we’d try another—it was a miracle when call forwarding to my cell phone came along—I was no longer stranded, and Damien could reach me anywhere.—LD

*

Melissa was a colleague of Damien’s lead counsel, Ed Mallett, at the time. Cally is a dear friend and, officially speaking, Damien’s adoptive mother, who had been writing letters to Damien from nearly the beginning of his incarceration. She and her husband, Douglas, funded Damien’s entire Rule 37 appeal.—LD

*

The father of one of the victims rushed the bench during Damien’s Rule 37 hearing. He was restrained and quickly escorted out of the courtroom.—LD

*

We were only permitted to have six people, some of them witnesses, attend our wedding in the prison. It was terribly hard to decide who to invite, although the reception afterward at a friend’s house was attended by everyone we knew and had become a part of our circle. I was excluded from the celebration, of course; while our friends and family toasted our union—and the love of my life—I sat alone in a prison cell.—DE

*

Paradise Lost 2: Revelations

*

It turned out we did see. We saw a lot from Eddie, Nicole Vandenberg, his publicist, and the entire Pearl Jam family. They played huge arena concerts, donating their incomes to the defense fund. Eddie played a private birthday party for a guy from Microsoft who in turn donated $300K. They were constantly looking for ways to help, and were always there when we needed them. When, in 2009, it made sense to put on a concert in Little Rock to raise awareness before the Supreme Court hearing, Pearl Jam donated all their time and energy and manpower to put on the show. Nicole and Ed came down to help Lorri the week before our release, and Ed’s home was the first place we went afterward.—DE

*

This was in reference to my Jukai ordination ceremony in the Rinzai Zen tradition of Japanese Buddhism, the first step toward priesthood. I had been practicing Zen Buddhism for probably two years at that point, and this was the point at which my teacher presented me with a Koan—a puzzle that cannot be solved with a rational mind—in a ceremony conducted by two priests.—DE

*

This was a screening at the Hot Springs Documentary Film Festival of

Paradise Lost 2

, and there was a discussion panel at the end of it. I don’t recall who the specific people were on this panel, though it was entirely different from any other screenings of the film I’d been to, because they invited people from both sides of the case to weigh in. The room was packed and emotions were running very high; it was the first time the film had been shown in Arkansas.—LD

*

Damien was offered $2,500 for his appearance in

Paradise Lost 2

, which for various reasons he couldn’t accept at the time of filming, so it was funny that Joe’s donation was so very similar . . .—LD

*

Frank King was the deacon from the nearby Catholic church who used to visit the prison. Freddie Nixon was on the board of the Arkansas Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty, but also a friend and support to the guys on death row.—LD

*

Dr. Phil was trying to get us to do a show, or a series of shows, about the case. Thank heavens we decided against it. It wouldn’t be until 2007 that we started doing media in earnest with some guidance.—LD

*

I’m talking about Submission, a bondage shop online at the time, not sandwiches.—DE

*

This was the draft of my first self-published book,

Almost Home

.—DE

*

Anna Phelan, screenwriter for

Gorillas in the Mist

and many other movies, wrote an early script for

Devil’s Knot

by Mara Leveritt. It was, to my mind, a great and truthful depiction of the case and our situation, although sadly it was ultimately shelved.—DE

*

I was only allowed to have three phone numbers on a list of people allowed to call the prison, and it often took months to change those numbers.—DE

*

It wasn’t long before we were talking on the phone, although as everything with the prison system tends to be, it was convoluted and expensive. The prison phone system is something most people don’t know anything about. Most state prisons have contracts with large phone companies and the calls are always collect, and the costs are hefty. There is always a connection charge—usually several dollars, and a per-minute fee after that. A call usually lasts 15 minutes before it’s cut off, then you must pay the surcharge again for another call. An out-of-state call can cost up to $25 for 15 minutes. Looking back, it’s shocking to realize that we ended up paying around $200K on phone calls alone.—LD

*

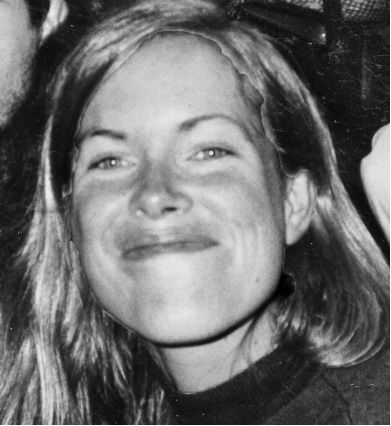

Here’s a photograph of me, taken at a Yankees game the day after Damien first called me. He’d promised to call the following day, although I’d forgotten to tell him I wouldn’t be home—my upstairs neighbor listened for the phone and ran downstairs to answer and explain my absence. In this photo, with my friends Luis and Julie, I’m keeping the happiest secret inside. When I read this letter, I am astounded by how accurate it was, in some ways. Looking back over the years, and what happened to both of us, the paths our lives would take—it was as if I were looking into a crystal ball. Even now, as our lives are unfolding in the free world, I am experiencing a sense of what my words forecasted. I’m increasingly grateful for all our patience.—LD

*

How I remember this time. I’m not a fainter, yet I keep reading these references to passing out. I do remember that when I flew to Arkansas, I wasn’t taking care of myself. I was doing this very emotional thing—going into a prison, seeing someone I loved who was on death row. I went about it in a very demanding way. I flew down and arrived late at night, got up very early after tossing back and forth in bed, went to a very early morning visit with Damien, then flew back to NY that very afternoon. I ate nothing, it seems, in the whole time I was traveling—too nervous. Just going into a prison is taxing. Later, when I lived in Arkansas and visitors would come, I would tell them they should spend the night before flying home. Going into the prison, seeing Damien—all of it is too exhausting, both mentally and physically. Yet I went about it this first time as if I were superhuman, and I wasn’t. Far from it. I suppose I really was out of my body for much of this, but then again, I was in the most surreal time of my life. When I read of this time, I actually don’t recognize myself. That’s how far I had pushed past my “acceptable” boundaries. My psyche was telling me that I was completely out of control, and my body was telling me that this was something only crazy people do. I wasn’t listening to either.—LD