1491 (48 page)

Adena influence in customs and artifacts can be spotted in archaeological sites from Indiana to Kentucky and all the way north to Vermont and even New Brunswick. For a long time researchers believed this indicated that the Adena had conquered other groups throughout this area, but many now believe that the influence was cultural: like European teenagers donning baggy pants and listening to hip-hop, Adena’s neighbors adopted its customs. Archaeologists sometimes call the area in which such cultural flows occur an “interaction sphere.” Both less and more than a nation, an interaction sphere is a region in which one society disseminates its symbols, values, and inventions to others; an example is medieval Europe, much of which fell under the sway of Gothic aesthetics and ideas. The Adena interaction sphere lasted from about 800

B.C.

to about 100

B.C.

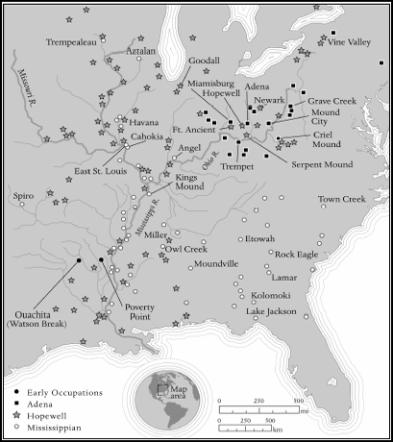

MOUNDBUILDERS, 3400 B.C.–1400 A.D.

Textbooks sometimes say that the Adena were succeeded by the Hopewell, but the relation is unclear; the Hopewell may simply have been a later stage of the same culture. The Hopewell, too, built mounds, and like the Adena seem to have spoken an Algonquian language. (“Hopewell” refers to the farmer on whose property an early site was discovered.) Based in southern Ohio, the Hopewell interaction sphere lasted until about 400

A.D.

and extended across two-thirds of what is now the United States. Into the Midwest came seashells from the Gulf of Mexico, silver from Ontario, fossil shark’s teeth from Chesapeake Bay, and obsidian from Yellowstone. In return the Hopewell exported ideas: the bow and arrow, monumental earthworks, fired pottery (Adena pots were not put into kilns), and, probably most important, the Hopewell religion.

The Hopewell apparently sought spiritual ecstasy by putting themselves into trances, perhaps aided by tobacco. In this enraptured state, the soul journeys to other worlds. As is usually the case, people with special abilities emerged to assist travelers through the portal to the numinous. Over time these shamans became gatekeepers, controlling access to the supernatural realm. They passed on their control and privileges to their children, creating a hereditary priesthood: counselors to kings, if not kings themselves. They acquired healing lore, mastered and invented ceremonies, learned the numerous divinities in the Hopewell pantheon. We know little of these gods today, because few of their images have endured to the present. Presumably shamans recounted their stories to attentive crowds; almost certainly, they explained when and where the gods wanted to build mounds.

In the context of the village, the mound, visible everywhere, was as much a beacon as a medieval cathedral. As with Gothic churches, which had plazas for the outdoor performance of sacred mystery plays, the mounds had greens before them: ritual spaces for public use. Details of the performances are lost, but there is every indication that they were exuberant affairs. “There is a stunning vigor about the Ohio Hopewell…,” Silverberg wrote,

a flamboyance and fondness for excess that manifests itself not only in the intricate geometrical enclosures and the massive mounds, but in these gaudy displays of conspicuous consumption [in the tombs]. To envelop a corpse from head to feet in pearls, to weigh it down in many pounds of copper, to surround it with masterpieces of sculpture and pottery, and then to bury everything under tons of earth—this betokens a kind of cultural energy that numbs and awes those who follow after.

Vibrant and elaborate, perhaps a little vulgar in its passion for display, Hopewell religion spread through most of the eastern United States in the first four centuries

A.D.

As with the expansion of Christianity, the new converts are unlikely to have understood the religion in the same way as its founders. Nonetheless, its impact was profound. In a mutated form, it may well have given impetus to the rise of Cahokia.

THE RISE AND FALL OF THE AMERICAN BOTTOM

Cahokia was one big piece in the mosaic of chiefdoms that covered the lower half of the Mississippi and the Southeast at the end of the first millennium

A.D.

Known collectively as “Mississippian” cultures, these societies arose several centuries after the decline of the Hopewell culture, and probably were its distant descendants. At any one time a few larger polities dominated the dozens or scores of small chiefdoms. Cahokia, biggest of all, was preeminent from about 950 to about 1250

A.D.

It was an anomaly: the greatest city north of the Río Grande, it was also the

only

city north of the Río Grande. Five times or more bigger than any other Mississippian chiefdom, Cahokia’s population of at least fifteen thousand made it comparable in size to London, but on a landmass without Paris, Córdoba, or Rome.

I call Cahokia a city so as to have a stick to beat it with, but it was not a city in any modern sense. A city provides goods and services for its surrounding area, exchanging food from the countryside for the products of its sophisticated craftspeople. By definition, its inhabitants are urban—they aren’t farmers. Cahokia, however, was a huge collection of farmers packed cheek by jowl. It had few specialized craftworkers and no middle-class merchants. On reflection, Cahokia’s dissimilarity to other cities is not surprising; having never seen a city, its citizens had to invent every aspect of urban life for themselves.

Despite the nineteenth-century fascination with the mounds, archaeologists did not begin to examine Cahokia thoroughly until the 1960s. Since then studies have gushed from the presses. By and large, they have only confirmed Cahokia’s status as a statistical outlier. Cahokia sat on the eastern side of the American Bottom. Most of the area has clayey soil that is hard to till and prone to floods. Cahokia was located next to the largest stretch of good farmland in the entire American Bottom. At its far edge, a forest of oak and hickory topped a line of bluffs. The area was little settled until as late as 600

A.D.,

when people trickled in and formed small villages, groups of a few hundred who planted gardens and boated up and down the Mississippi to other villages. As the millennium approached, the American Bottom had a resident population of several thousand. Then, without much apparent warning, there was, according to the archaeologist Timothy R. Pauketat of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, what has been called a “Big Bang”—a few decades of tumultuous change.

Cahokia’s mounds emerged from the Big Bang, along with the East St. Louis mound complex a mile away (the second biggest, after Cahokia, though now mostly destroyed) and the St. Louis mounds just across the Mississippi (the fourth biggest). Monks Mound was the first and most grandiose of the construction projects. Its core is a slab of clay about 900 feet long, 650 feet wide, and more than 20 feet tall. From an engineering standpoint, clay should never be selected as the bearing material for a big earthen monument. Clay readily absorbs water, expanding as it does. The American Bottom clay, known as smectite clay, is especially prone to swelling: its volume can increase by a factor of eight. Drying, it shrinks back to its original dimensions. Over time the heaving will destroy whatever is built on top of it. The Cahokians’ solution to this problem was discovered mainly by Woods, the University of Kansas archaeologist and geographer, who has spent two decades excavating Monks Mound.

To minimize instability, he told me, the Cahokians kept the slab at a constant moisture level: wet but not too wet. Moistening the clay was easy—capillary action will draw up water from the floodplain, which has a high water table. The trick is to stop evaporation from drying out the top. In an impressive display of engineering savvy, the Cahokians encapsulated the slab, sealing it off from the air by wrapping it in thin, alternating layers of sand and clay. The sand acts as a shield for the slab. Water rises through the clay to meet it, but cannot proceed further because the sand is too loose for further capillary action. Nor can the water evaporate; the clay layers atop the sand press down and prevent air from coming in. In addition, the sand lets rainfall drain away from the mound, preventing it from swelling too much. The final result covered almost fifteen acres and was the largest earthen structure in the Western Hemisphere; though built out of unsuitable material in a floodplain, it has stood for a thousand years.

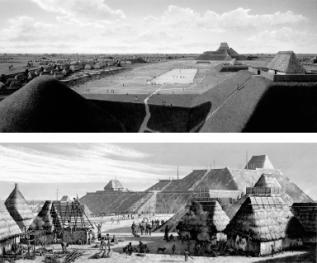

Reconstructions of Cahokia, the greatest city north of the Río Grande, ca. 1250

A.D.

Because the slab had to stay moist, it must have been built and covered quickly, a task requiring a big workforce. Evidence suggests that people moved from miles around to the American Bottom to be part of the project. If the ideas of Pauketat, the University of Illinois archaeologist, are correct, the immigrants probably came to regret their decision to move. To his way of thinking, the Big Bang occurred after a single ambitious person seized power, perhaps in a coup. Although his reign may have begun idealistically, Cahokia quickly became an autocracy; in an Ozymandiac extension of his ego, the supreme leader set in motion the construction projects. Loyalists forced immigrants to join the labor squads, maintaining control with the occasional massacre. Burials show the growing power of the elite: in a small mound half a mile south of Monks Mound, archaeologists in the late 1960s uncovered six high-status people interred with shell beads, copper ornaments, mica artworks—and the sacrificed bodies of more than a hundred retainers. Among them were fifty young women who had been buried alive.

Woods disagrees with what he calls the “proto-Stalinist work camp” scenario. Nobody was

forced

to erect Monks Mound, he says. Despite the intermittent displays of coercion, he says, Cahokians put it up “because they wanted to.” They “were proud to be part of these symbols of community identity.” Monks Mound and its fellows were, in part, a shout-out to the world—Look at us! We’re doing something different! It was also the construction of a landscape of sacred power, built in an atmosphere of ecstatic religious celebration. The American Bottom, in this scenario, was the site of one of the world’s most spectacular tent revivals. Equally important, Woods says, the mound city was in large part an outgrowth of the community’s previous adoption of maize.

Before Cahokia’s rise, people were slowly hunting the local deer and bison populations to extinction. The crops in the Eastern Agricultural Complex could not readily make up the difference. Among other problems, most had small seeds—imagine trying to feed a family on sesame seeds, and you have some idea of what it would have been like to subsist on maygrass. Maize had been available since the first century

B.C.

(It would have arrived sooner, but Indians had to breed landraces that could tolerate the cooler weather, shorter growing seasons, and longer summer days of the north.) The Hopewell, however, almost ignored it. Somewhere around 800

A.D.

their hungry successors took another look at the crop and liked what they saw. The American Bottom, with its plenitude of easily cleared, maize-suitable land, was one of the best places to grow it for a considerable distance. The newcomers needed to store their harvests for the winter, a task most efficiently accomplished with a communal granary. The granary needed to be supervised—an invitation to develop centralized power. Growth happened fast and may well have been hurried along by a charismatic leader, Woods said, but something like Cahokia probably would have happened anyway.