1491 (51 page)

THE HUNDRED YEARS’ WAR

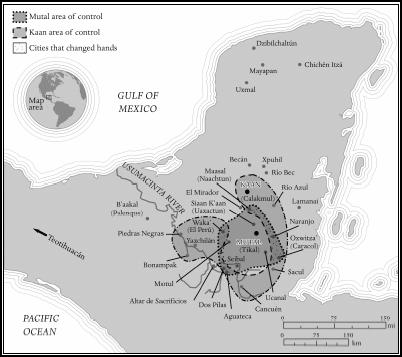

Kaan and Mutal Battle to Control the Maya Heartland, 526–682

A.D.

The war between Kaan and Mutal lasted more than a century and consumed much of the Maya heartland. Kaan’s strategy was to surround Mutal and its subordinate city-states with a ring of enemies. By conquest, negotiation, and marriage alliance, Kaan succeeded in encircling its enemy—but not in winning the war.

Kaan did not directly occupy Mutal; victorious Maya cities rarely had the manpower to rule their rivals directly. Instead, in the by-now familiar hegemonic pattern, they tried to force the rulers of the vanquished state to become their vassals. If an enemy sovereign was slain, as apparently happened in Mutal, the conquerors often didn’t emplace a new one; kings were divine, and thus by definition irreplaceable. Instead the victorious force simply quit the scene, hoping that any remaining problems would disappear in the ensuing chaos. This strategy was partly successful in Mutal—not a single dated monument was erected in the city for a century. Because the city’s postattack rulers had (at best) distant connections to the slain legitimate king, they struggled for decades to get on their feet. Unhappily for Kaan, they eventually did it.

The agent for Mutal’s return was its king, Nuun Ujol Chaak. Taking the helm of the city in 620

A.D.,

he was as determined to reestablish his city’s former glory as Kaan’s rulers were to prevent it. He suborned Kaan’s eastern neighbor, Naranjo, which attacked Mutal’s former ally, Oxwitza’. The ensuing conflict spiraled out to involve the entire center of the Maya realm. Decades of conflict, including a long civil war in Mutal, led to the formation of two large blocs, one dominated by Mutal, the other by Kaan. As cities within the blocs traded attacks with each other, half a dozen cities ended up in ruins, including Naranjo, Oxwitza’, Mutal, and Kaan. The story was not revealed in full until 2001, when a storm uprooted a tree in the ruin of Dos Pilas, a Mutal outpost. In the hole from its root ball archaeologists discovered a set of steps carved with the biography of B’alaj Chan K’awiil, a younger brother or half brother to Mutal’s dynasty-restoring king, Nuun Ujol Chaak. As deciphered by the epigrapher Stanley Guenter, the staircase and associated monuments reveal the turbulent life of a great scalawag who spent his life alternately running from the armies of Kaan and Mutal and trying to set them against each other.

Eventually an army under Nuun Ujol Chaak met the forces of Kaan on April 30, 679. Maya battles rarely involved massive direct engagements. This was an exception. In an unusual excursion into the high-flown, the inscriptions on the stairway apostrophized the gore: “the blood was pooled and the skulls of the Mutal people were piled into mountains.” B’alaj Chan K’awiil was carried into battle in the guise of the god Ik’ Sip, a deity with a black-painted face. In this way he acquired its supernatural power. The technique worked, according to the stairway: “B’alaj Chan K’awiil brought down the spears and shields of Nuun Ujol Chaak.” Having killed his brother, the vindicated B’alaj Chan K’awiil took the throne of Mutal.

In a celebration, B’alaj Chan K’awiil joined the rulers of Kaan in a joyous ceremonial dance on May 10, 682. But even as he danced with his master, a counterrevolutionary coup in Mutal placed Nuun Ujol Chaak’s son onto the throne, from where he quickly became a problem. On August 5, 695, Kaan soldiers once again went into battle against Mutal. Bright with banners, obsidian blades gleaming in the sun, the army advanced on the long-term enemy it had routed so many times before—and was utterly defeated. In a psychological blow, Mutal captured the effigy of a Kaan patron deity—an enormous supernatural jaguar—that its army carried into battle. A month later, in a mocking ceremonial pageant, the king of Mutal paraded around with the effigy strapped to the back of his palanquin.

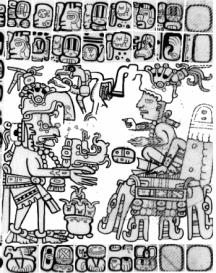

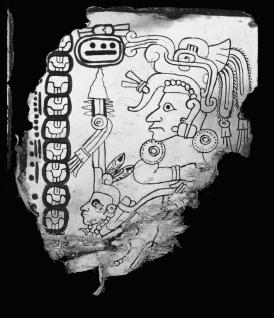

Maya “books” consisted of painted bark folded accordion-style into sheaves known as codexes. Time and the Spanish destroyed all but four codexes, and even those are fragmentary (above, a detail from the Paris codex, somewhat reconstructed; right, a piece of the Grolier codex).

Kaan’s loss marks the onset of the Maya collapse. Kaan never recovered from its defeat; Mutal lasted another century before it, too, sank into oblivion. Between 800 and 830

A.D.,

most of the main dynasties fell; cities winked out throughout the Maya heartland. Mutal’s last carved inscription dates to 869; soon after, its great public spaces were filled with squatters. In the next hundred years, the population of most southern areas declined by at least three-quarters.

The disaster was as much cultural as demographic; the Maya continued to exist by the million, but their central cities did not. Morley, the Harvard archaeologist, documented the cultural disintegration when he discovered that Maya inscriptions with Long Count dates rise steadily in number from the first known example, at Mutal in 292

A.D.;

peak in about 790; and cease altogether in 909. The decline tracks the Maya priesthood’s steady loss of the scientific expertise necessary to maintain its complex calendars.

The fall has been laid at the door of overpopulation, overuse of natural resources, and drought. It is true that the Maya were numerous; archaeologists agree that more people lived in the heartland in 800

A.D.

than today. And the Maya indeed had stretched the meager productive capacity of their homeland. The evidence for drought is compelling, too. Four independent lines of evidence—ethnohistoric data; correlations between Yucatán rainfall and measured temperatures in western Europe; measurements of oxygen variants in lake sediments associated with drought; and studies of titanium levels in the Caribbean floor, which are linked to rainfall—indicate that the Maya heartland was hit by a severe drought at about the time of its collapse. Water levels receded so deeply, the archaeologist Richardson Gill argued in 2000, that “starvation and thirst” killed millions of Maya. “There was nothing they could do. There was nowhere they could go. Their whole world, as they knew it, was in the throes of a burning, searing, brutal drought…. There was nothing to eat. Their water reservoirs were depleted, and there was nothing to drink.”

The image is searing: a profligate human swarm unable to overcome the anger of Nature. Yet Gill’s critics dismissed it. Turner, the Clark geographer, was skeptical about the evidence for the killer drought. But even if it happened, he told me, “The entire Maya florescence took place during a prolonged dry period.” Because they had spent centuries managing scarce water supplies, he thought it unlikely that they would have fallen quick victim to drought.

Moreover, the collapse did not occur in the pattern one would expect if drought were the cause: in general, the wetter southern cities fell first and hardest. Meanwhile, northern cities like Chichén Itzá, Uxmal, and Coba not only survived the dearth of rain, they prospered. In the north, in fact, the areas with the poorest natural endowments and the greatest susceptibility to drought were the most populous and successful. “How and why, then,” asked Bruce H. Dahlin, an archaeologist at Howard University, “did the onset of prolonged drought conditions simultaneously produce a disaster in the southern and central lowlands—where one would least expect it—and continued growth and development in the north, again where one would least expect it?”

Dahlin argued in 2002 that Chichén Itzá had adapted to the drought by instituting “sweeping economic, military, political, and religious changes.” Previous Maya states had been run by all-powerful monarchs who embodied the religion and monopolized trade. Almost all public announcements and ceremonies centered on the figure of the paramount ruler; in the stelae that recount royal deeds, the only other characters are, almost always, the king’s family, other kings, and supernatural figures. Beginning in the late ninth or early tenth century

A.D.,

public monuments in Chichén Itzá deemphasized the king, changing from official narratives of regal actions to generalized, nontextual images of religion, commerce, and war.

In the new regime, economic power passed to a new class of people: merchants who exchanged salt, chocolate, and cotton from Chichén Itzá for a host of goods from elsewhere in Mesoamerica. In previous centuries trade focused on symbolic goods that directly engaged the king, such as jewelry for the royal family. During the drought, something like markets emerged. Dahlins calculated that the evaporation pans outside a coastal satellite of Chichén Itzá would have produced at least three thousand tons of salt for export every year; in return, the Maya acquired tons of obsidian for blades, semiprecious stones for jewelry, volcanic ash for tempering pottery, and, most important, maize. Like Japan, which exports consumer electronics and imports beef from the United States and wheat from Australia, Chichén Itzá apparently traded its way through the drought.

The contrast between north and south is striking—and instructive. The obvious difference between them was the century and a half of large-scale warfare in the south. Both portions of the Maya realm depended on artificial landscapes that required constant attention. But only in the south did the Maya elite, entranced by visions of its own glory, take its hands off the switch. Drought indeed stressed the system, but the societal disintegration in the south was due not to surpassing inherent ecological limits but the political failure to find solutions. In our day the Soviet Union disintegrated after drought caused a series of bad harvests in the 1970s and 1980s, but nobody argues that climate ended Communist rule. Similarly, one should grant the Maya the dignity of assigning them responsibility for their failures as well as their successes.

Cahokia and the Maya, fire and maize: all exemplify the new view of indigenous impacts on the environment. When scholars first increased their estimates of Indians’ ecological management they met with considerable resistance, especially from ecologists and environmentalists. The disagreement, which has ramifying political implications, is encapsulated by Amazonia, the subject to which I will now turn. In recent years a growing number of researchers has argued that Indian societies there had enormous environmental impacts. Like the landscapes of Cahokia and the Maya heartland, some anthropologists say, the great Amazon forest is also a cultural artifact—that is, an artificial object.