1491 (49 page)

THE AMERICAN BOTTOM, 1300 A.D.

Maize also played a role in the city’s disintegration. Cahokia represented the first time Indians north of the Río Grande had tried to feed and shelter fifteen thousand people in one place, and they made beginner’s mistakes. To obtain fuel and construction material and to grow food, they cleared trees and vegetation from the bluffs to the east and planted every inch of arable land. Because the city’s numbers kept increasing, the forest could not return. Instead people kept moving further out to get timber, which then had to be carried considerable distances. Having no beasts of burden, the Cahokians themselves had to do all the carrying. Meanwhile, Woods told me, the city began outstripping its water supply, a “somewhat wimpy” tributary called Canteen Creek. To solve both of these problems at once, the Cahokians apparently changed its course, which had consequences that they cannot have anticipated.

Nowadays Cahokia Creek, which flows from the north, and Canteen Creek, which flows from the east, join together at a point about a quarter mile northeast of Monks Mound. On its way to the Mississippi, the combined river then wanders, quite conveniently, within two hundred yards of the central plaza. Originally, though, the smaller Canteen Creek alone occupied that channel. Cahokia Creek drained into a lake to the northwest, then went straight to the Mississippi, bypassing Cahokia altogether. Sometime between 1100 and 1200

A.D.,

according to Woods’s as-yet unpublished research, Cahokia Creek split in two. One fork continued as before, but the second, larger fork dumped into Canteen Creek. The combined river provided much more water to the city—it was about seventy feet wide. And it also let woodcutters upstream send logs almost to Monks Mound. A natural inference, to Woods’s way of thinking, is that the city, in a major public works project, “intentionally diverted” Cahokia Creek.

In summer, heavy rains lash the Mississippi Valley. With the tree cover stripped from the uplands, rainfall would have sluiced faster and heavier into the creeks, increasing the chance of floods and mudslides. Because the now-combined Cahokia and Canteen Creeks carried much more water than had Canteen Creek alone, washouts would have spread more widely across the American Bottom than would have been the case if the rivers had been left alone. Beginning in about 1200

A.D.,

according to Woods, Cahokia’s maize fields repeatedly flooded, destroying the harvests.

The city’s problems were not unique. Cahokia’s rise coincided with the spread of maize throughout the eastern half of the United States. The Indians who adopted it were setting aside millennia of tradition in favor of a new technology. In the past, they had shaped the landscape mainly with fire; the ax came out only for garden plots of marshelder and little barley. As maize swept in, Indians burned and cleared thousands of acres of land, mainly in river valleys. As in Cahokia, floods and mudslides rewarded them. (How do archaeologists know this? They know it from sudden increases in river sedimentation coupled with the near disappearance of pollen from bottomland trees in those sediments.) Between about 1100 and 1300

A.D.,

cataclysms afflicted Indian settlements from the Hudson Valley to Florida.

Apparently the majority learned from mistakes; after this time, archaeologists don’t see this kind of widespread erosion, though they do see lots and lots of maize. A traveler in 1669 reported that six square miles of maize typically encircled Haudenosaunee villages. This estimate was very roughly corroborated two decades later by the Marquis de Denonville, governor of New France, who destroyed the annual harvest of four adjacent Haudenosaunee villages to deter future attacks. Denonville reported that he had burned 1.2 million bushels of maize—42,000 tons. Today, as I mentioned in Chapter 6, Oaxacan farmers typically plant roughly 1.25–2.5 acres to harvest a ton of landrace maize. If that relation held true in upstate New York—a big, but not ridiculous assumption—arithmetic suggests that the four villages, closely packed together, were surrounded by between eight and sixteen square miles of maize fields.

Between these fields was the forest, which Indians were subjecting to parallel changes. Sometime in the first millennium

A.D.,

the Indians who had burned undergrowth to facilitate grazing began systematically replanting large belts of woodland, transforming them into orchards for fruit and mast (the general name for hickory nuts, beechnuts, acorns, butternuts, hazelnuts, pecans, walnuts, and chestnuts). Chestnut was especially popular—not the imported European chestnut roasted on Manhattan street corners in the fall, but the smaller, soft-shelled, deeply sweet native American chestnut, now almost extinguished by chestnut blight. In colonial times, as many as one out of every four trees in between southeastern Canada and Georgia was a chestnut—partly the result, it would seem, of Indian burning and planting.

Hickory was another favorite. Rambling through the Southeast in the 1770s, the naturalist William Bartram observed Creek families storing a hundred bushels of hickory nuts at a time. “They pound them to pieces, and then cast them into boiling water, which, after passing through fine strainers, preserves the most oily part of the liquid” to make a thick milk, “as sweet and rich as fresh cream, an ingredient in most of their cookery, especially hominy and corncakes.” Years ago a friend and I were served hickory milk in rural Georgia by an eccentric backwoods artist named St. EOM who claimed Creek descent. Despite the unsanitary presentation, the milk was ambrosial—fragrantly nutty, delightfully heavy on the tongue, unlike anything I had encountered before.

Within a few centuries, the Indians of the eastern forest reconfigured much of their landscape from a patchwork game park to a mix of farmland and orchards. Enough forest was left to allow for hunting, but agriculture was an increasing presence. The result was a new “balance of nature.”

From today’s perspective, the

success

of the transition is striking. It was so sweeping and ubiquitous that early European visitors marveled at the number of nut and fruit trees and the big clearings with only a dim apprehension that the two might be due to the same human source. One reason that Bartram failed to understand the artificiality of what he saw was that the surgery was almost without scars; the new landscape functioned smoothly, with few of the overreaches that plagued English land management. Few of the overreaches, but not none: Cahokia was a glaring exception.

A friend and I visited Cahokia in 2002. Woods, who lived nearby, kindly agreed to show us around. The site is now a state park with a small museum. From Monks Mound we walked halfway across the southern plaza and then stopped to look back. From the plaza, Woods pointed out, the priests at the summit could not be seen. “There was smoke and noise and sacred activity constantly going on up there, but the peasants didn’t know what they were doing.” Nonetheless, average Cahokians understood the intent: to assure the city’s continued support by celestial forces. “And

that

justification fell apart with the floods,” Woods said.

There is little indication that the Cahokia floods killed anyone, or even led to widespread hunger. Nonetheless, the string of woes provoked a crisis of legitimacy. Unable to muster the commanding vitality of their predecessors, the priestly leadership responded ineffectively, even counterproductively. Even as the flooding increased, it directed the construction of a massive, two-mile-long palisade around the central monuments, complete with bastions, shielded entryways, and (maybe) a catwalk up top. The wall was built in such a brain-frenzied hurry that it cut right through some commoners’ houses.

Cahokia being the biggest city around, it seems unlikely that the palisade was needed to deter enemy attack (in the event, none materialized). Instead it was probably created to separate elite from hoi polloi, with the goal of emphasizing the priestly rulers’ separate, superior, socially critical connection to the divine. At the same time the palisade was also intended to welcome the citizenry—anyone could freely pass through its dozen or so wide gates. Constructed at enormous cost, this porous architectural folly consumed twenty thousand trees.

More consequential, the elite revamped Monks Mound. By extending a low platform from one side, they created a stage for priests to perform ceremonies in full view of the public. According to Woods’s acoustic simulations, every word should have been audible below, lifting the veil of secrecy. It was the Cahokian equivalent of the Reformation, except that the Church imposed it on itself. At the same time, the nobles hedged their bets. Cahokia’s rulers tried to bolster their position by building even bigger houses and flaunting even more luxury goods like fancy pottery and jewelry made from exotic semiprecious stones.

It did no good. A catastrophic earthquake razed Cahokia in the beginning of the thirteenth century, knocking down the entire western side of Monks Mound. In 1811 and 1812 the largest earthquakes in U.S. history abruptly lifted or lowered much of the central Mississippi Valley by as much as twelve feet. The Cahokia earthquake, caused by the same fault, was of similar magnitude. It must have splintered many of the city’s wood-and-plaster buildings; fallen torches and scattered cooking fires would have ignited the debris, burning down most surviving structures. Water from the rivers, shaken by the quake, would have sloshed onto the land in a mini-tsunami.

Already reeling from the floods, Cahokia never recovered from the earthquake. Its rulers rebuilt Monks Mound, but the poorly engineered patch promptly sagged. Meanwhile the social unrest turned violent; many houses went up in flames. “There was a civil war,” Woods said. “Fighting in the streets. The whole polity turned in on itself and tore itself apart.”

For all their energy, Cahokia’s rulers made a terrible mistake: they did not attempt to fix the problem directly. True, the task would not have been easy. Trees cannot be replaced with a snap of the fingers. Nor could Cahokia Creek readily be reinstalled in its original location. “Once the water starts flowing in the new channel,” Woods said, “it is almost impossible to put it back in the old as the new channel rapidly downcuts and establishes itself.”

Given Cahokia’s engineering expertise, though, solutions were within reach: terracing hillsides, diking rivers, even moving Cahokia. Like all too many dictators, Cahokia’s rulers focused on maintaining their hold over the people, paying little attention to external reality. By 1350

A.D.

the city was almost empty. Never again would such a large Indian community exist north of Mexico.

HUNDRED YEARS’ WAR

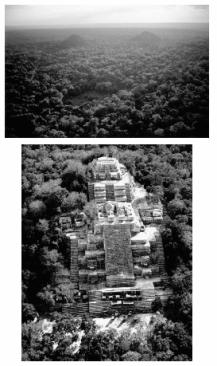

In the early 1980s I visited Chetumal, a coastal city on the Mexico-Belize border. A magazine had asked me to cover the intellectual ferment caused by the decipherment of Maya hieroglyphics. In researching the article, the photographer Peter Menzel and I became intrigued by the then little-known site of Calakmul, whose existence had been first reported five decades before. Although it was the biggest of all Maya ruins, it had never felt an archaeologist’s trowel. Its temples and villas, enveloped in thick tropical forest, were as close to a lost city as we would ever be likely to see. Before visiting Calakmul, though, Peter wanted to photograph it from the air. Chetumal had the nearest airport, which was why we went there.

A

BOVE

: As late as the 1980s, the Maya city of Kaan (now Calakmul) was encased in vegetation (top). Excavations have now revealed the pyramids beneath the trees (the right-hand mound in the top photo is the pyramid at bottom), exemplifying the recent explosion of knowledge about the Maya.