1812: The Navy's War (25 page)

Early in his tenure Warren recognized, as Admiral Lord Richard Howe did during the Revolutionary War, that it was impossible to establish even the semblance of an effective blockade without a much larger fleet. But when Warren requested more ships, the Admiralty told him to make do with what he had—the same advice given to Admiral Howe. The United States, after all, was a secondary theater. The Admiralty was already stretched thin blockading Napoleonic Europe, convoying merchant vessels, and servicing a sprawling overseas empire.

The American navy became so annoying, however, that the Admiralty grudgingly dispatched additional ships, increasing Warren’s sail of the line from six to ten, adding a 50-gun ship, bringing his frigate total up to thirty-four, and increasing the number of sloops of war to thirty-eight. With the various other smaller vessels at his command, Warren now had a total of ninety-seven warships. In addition, the Admiralty was cutting down four seventy-fours and converting them to razees (a sail of the line cut down and converted to a heavy frigate), and sending six to eight more war brigs.

The four additional sail of the line, along with a few frigates, came from the Cadiz station at the end of 1812, under the command of Rear Admiral George Cockburn, a fighter whom the Admiralty hoped would inject a more aggressive spirit into Warren’s operation. And Captain Henry Hotham, a notably harsh disciplinarian, was sent to be Warren’s captain of the fleet.

With the addition of all these warships, the Admiralty expected quick results, particularly when, as they never tired of telling Warren, the Americans had so few men-of-war. London continued to emphasize that the best way to deal with the American navy and privateers was to blockade them.

Even with an expanded fleet, however, blockading the vast American coast was exceptionally difficult. The Admiralty conceded that during the winter months of November through March weather conditions made northern ports tough to blockade. Contrary winds regularly blew ships off their stations, while the same winds were fair for swift-sailing privateers or warships to sortie. Recurring fog in all ports, north and south, blinded blockaders and allowed courageous American skippers to sneak past them.

Thus, no matter what Warren did, privateers were sure to roam in great numbers, as they did during the Revolutionary War, endangering, among other things, the shipment of vital supplies to the Duke of Wellington. It was all well and good to keep the duke supplied with American food through the issuing of licenses, but this could be negated by privateers capturing everything else coming from the British Isles, including even essential shoes for Wellington’s army.

WHILE LONDON WAS trying to get its blockade up and running, Commodore Rodgers and his colleagues were preparing for extended cruises against Britain’s navy and commerce. During the first week of October—long before Admiral Warren was settled in his new post—Rodgers had the

President

repaired, provisioned, and set to sail from Boston. The

Congress

was ready at the same time, but Jacob Jones and the

Wasp

were in Philadelphia. Jones would have to rendezvous with the

President

at sea. Rodgers ordered him to patrol in specific latitudes north of Bermuda, where they could meet later.

President

repaired, provisioned, and set to sail from Boston. The

Congress

was ready at the same time, but Jacob Jones and the

Wasp

were in Philadelphia. Jones would have to rendezvous with the

President

at sea. Rodgers ordered him to patrol in specific latitudes north of Bermuda, where they could meet later.

Rodgers and Decatur left Boston together on October 8 with the

President

, the

Congress

, the

United States

, and the

Argus

. They had no trouble getting to sea. Two days later, in the afternoon, Rodgers caught a fleeting glimpse of the British frigate

Nymphe

, but lack of wind and the approach of night prevented him from chasing her. The next day, October 11, Rodgers split off from Decatur, steering the

President

and the

Congress

in an easterly direction, while Decatur stood to the southeast with the

United States

and the

Argus

. The following day, the

Argus

separated from Decatur and shaped a course that would take her to the northeast coast of South America—a high-traffic area.

President

, the

Congress

, the

United States

, and the

Argus

. They had no trouble getting to sea. Two days later, in the afternoon, Rodgers caught a fleeting glimpse of the British frigate

Nymphe

, but lack of wind and the approach of night prevented him from chasing her. The next day, October 11, Rodgers split off from Decatur, steering the

President

and the

Congress

in an easterly direction, while Decatur stood to the southeast with the

United States

and the

Argus

. The following day, the

Argus

separated from Decatur and shaped a course that would take her to the northeast coast of South America—a high-traffic area.

On October 15 lookouts aboard the

President

spied a strange ship, and Rodgers put on all sail in chase. Not long afterward, the

President

’s main topgallant carried away, but Rodgers persevered and caught his prey. She turned out to be the 10-gun British packet

Swallow

, traveling from Kingston, Jamaica, to Falmouth, England, and she was carrying an astounding eighty-one boxes of gold and silver specie (coins), weighing ten tons—nearly $200,000 dollars, a king’s ransom. A few hours later, after Rodgers had taken all the money aboard the

President

, he happened on a pathetic-looking American schooner, the

Eleanor

. A storm had carried away both her masts. Only the captain’s ingenuity and luck kept her afloat, but his chances of reaching port were next to nothing. To the captain’s great surprise and joy, Rodgers gave him the

Swallow

.

President

spied a strange ship, and Rodgers put on all sail in chase. Not long afterward, the

President

’s main topgallant carried away, but Rodgers persevered and caught his prey. She turned out to be the 10-gun British packet

Swallow

, traveling from Kingston, Jamaica, to Falmouth, England, and she was carrying an astounding eighty-one boxes of gold and silver specie (coins), weighing ten tons—nearly $200,000 dollars, a king’s ransom. A few hours later, after Rodgers had taken all the money aboard the

President

, he happened on a pathetic-looking American schooner, the

Eleanor

. A storm had carried away both her masts. Only the captain’s ingenuity and luck kept her afloat, but his chances of reaching port were next to nothing. To the captain’s great surprise and joy, Rodgers gave him the

Swallow

.

The

President

then headed toward the Canary Islands, and on November 1, when she was four hundred miles southwest of the Azores, lookouts spied three sails to the southward. Rodgers, accompanied by the

Congress

, gave chase, and caught one, but the other two escaped. (One of the escapees was the 36-gun British frigate

Galatea

, a ship Rodgers would have given his right arm to fight.) The prize was the 10-gun

Argo

, a whaler stuffed with spermaceti oil, whalebone, and ebony, returning to England after a successful cruise in the Eastern Pacific. On the way home she had stopped at St. Helena, as many British ships did coming from the Pacific. When her captain reached St. Helena, he must have felt fortunate to have the

Galatea

to protect him on the way to England. Being captured by two American men-of-war must have astonished him.

President

then headed toward the Canary Islands, and on November 1, when she was four hundred miles southwest of the Azores, lookouts spied three sails to the southward. Rodgers, accompanied by the

Congress

, gave chase, and caught one, but the other two escaped. (One of the escapees was the 36-gun British frigate

Galatea

, a ship Rodgers would have given his right arm to fight.) The prize was the 10-gun

Argo

, a whaler stuffed with spermaceti oil, whalebone, and ebony, returning to England after a successful cruise in the Eastern Pacific. On the way home she had stopped at St. Helena, as many British ships did coming from the Pacific. When her captain reached St. Helena, he must have felt fortunate to have the

Galatea

to protect him on the way to England. Being captured by two American men-of-war must have astonished him.

Rodgers now shaped a course that took him down the trades west of the Cape Verde Islands, a Portuguese colony four hundred miles off the coast of Africa. When he reached the fiftieth meridian, he steered west toward the Bermudas, where he hoped to rendezvous with Jacob Jones and the

Wasp

. He cruised for four weeks north and west of the Bermudas but never saw Jones. With water and supplies running low, he reluctantly stood for Boston, putting in on the last day of 1812.

Wasp

. He cruised for four weeks north and west of the Bermudas but never saw Jones. With water and supplies running low, he reluctantly stood for Boston, putting in on the last day of 1812.

Rodgers had been cruising for eighty-five days, and he had covered 11,000 miles, but his accomplishments had been slight. “We chased everything we saw,” he told Secretary Hamilton. Unfortunately, he saw very little. He did have the $200,000 taken from the

Swallow

, and that was considerable consolation. It not only meant prize money but was a serious blow to Britain’s war effort. Gold and silver were of great importance to Wellington in the Iberian Peninsula. In order to win the support of the Spanish people, he paid for all the supplies he took in gold and silver. It was a practice that served him well but strained the British treasury—and made losses like that of the

Swallow

all the more devastating.

Swallow

, and that was considerable consolation. It not only meant prize money but was a serious blow to Britain’s war effort. Gold and silver were of great importance to Wellington in the Iberian Peninsula. In order to win the support of the Spanish people, he paid for all the supplies he took in gold and silver. It was a practice that served him well but strained the British treasury—and made losses like that of the

Swallow

all the more devastating.

WHILE RODGERS WAS stalking British vessels in the mid-Atlantic, Jacob Jones, in obedience to his orders, had sailed the

Wasp

beyond the Delaware Capes on October 13 and set a course that would take him north of the Bermudas to rendezvous with the

President

. On the sixteenth a heavy gale struck, and Jones lost his jib boom and two men. Organizing a jury rig, he carried on, the sea running high after the storm. The following night at 11:30, in latitude 37° north and longitude 65° west, lookouts discovered several sails in the distance, two of them large. They looked to be part of a British convoy accompanied by an escort. Jones stood from them for a time and then, for the remainder of the night, steered a parallel course. At daylight on Sunday the eighteenth, he saw them ahead. They were six large, armed merchantmen, mounting sixteen to eighteen guns with a powerful British gun brig for an escort. Without hesitating, he went after them.

Wasp

beyond the Delaware Capes on October 13 and set a course that would take him north of the Bermudas to rendezvous with the

President

. On the sixteenth a heavy gale struck, and Jones lost his jib boom and two men. Organizing a jury rig, he carried on, the sea running high after the storm. The following night at 11:30, in latitude 37° north and longitude 65° west, lookouts discovered several sails in the distance, two of them large. They looked to be part of a British convoy accompanied by an escort. Jones stood from them for a time and then, for the remainder of the night, steered a parallel course. At daylight on Sunday the eighteenth, he saw them ahead. They were six large, armed merchantmen, mounting sixteen to eighteen guns with a powerful British gun brig for an escort. Without hesitating, he went after them.

When he did, the 22-gun

Frolic

, under Captain Thomas Whinyates, dropped astern of the merchantmen and hoisted Spanish colors to decoy the

Wasp

and allow the convoy to escape. As Whinyates watched the

Wasp

bearing down, he must have been apprehensive. His brig was not in good shape. The same violent gale that had struck

Wasp

the night before had carried away the

Frolic

’s main yard, ripped up her topsails, and sprang the main topmast. Whinyates was repairing damages when he saw the

Wasp

.

Frolic

, under Captain Thomas Whinyates, dropped astern of the merchantmen and hoisted Spanish colors to decoy the

Wasp

and allow the convoy to escape. As Whinyates watched the

Wasp

bearing down, he must have been apprehensive. His brig was not in good shape. The same violent gale that had struck

Wasp

the night before had carried away the

Frolic

’s main yard, ripped up her topsails, and sprang the main topmast. Whinyates was repairing damages when he saw the

Wasp

.

Jones closed with the enemy quickly, and at 11:30, when he was within sixty yards, Whinyates fired a broadside, which did little damage but initiated a fierce exchange. The

Frolic

’s guns hit the

Wasp

hard, and it looked at first as if Whinyates would prevail. But Jones continued to close, and the two ships ran alongside each other, firing as they went. After several minutes, Jones shot away the

Frolic

’s gaff and the head braces, and since there was no sail on the mainmast, the brig was unmanageable. Jones was now able to rake her fore and aft. Within minutes, Jones could see that every brace and most of Whinyates’s rigging had been shot away.

Frolic

’s guns hit the

Wasp

hard, and it looked at first as if Whinyates would prevail. But Jones continued to close, and the two ships ran alongside each other, firing as they went. After several minutes, Jones shot away the

Frolic

’s gaff and the head braces, and since there was no sail on the mainmast, the brig was unmanageable. Jones was now able to rake her fore and aft. Within minutes, Jones could see that every brace and most of Whinyates’s rigging had been shot away.

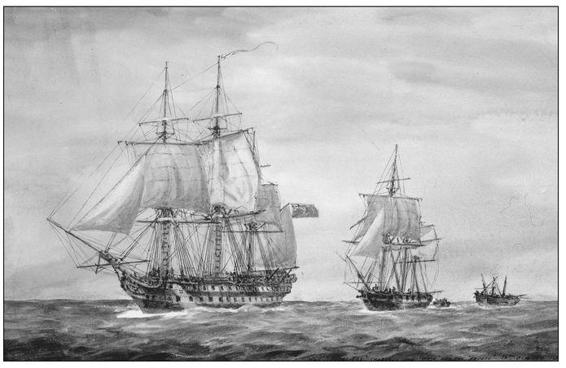

Figure 10.1: Irwin Bevan, Poictiers

Takes

Wasp

, 19 October 1812

(courtesy of Mariner’s Museum, Newport News, Virginia).

Takes

Wasp

, 19 October 1812

(courtesy of Mariner’s Museum, Newport News, Virginia).

Jones continued to lessen the distance between the ships until they were almost touching. The unmanageable

Frolic

’s bowsprit fell between the

Wasp

’s main and mizzen rigging, at which point First Lieutenant James Biddle led a boarding party onto Whinyates’s deck. He found every British officer injured and a sickening number of men killed or wounded. No more than twenty were left to fight. There was nothing Whinyates could do but surrender. In his report to the Admiralty he insisted that had the

Frolic

not been so beaten up in the gale he would have taken the

Wasp

. Jones, of course, would have disputed that. In the end, at least thirty of the

Frolic

’s crew were killed and about fifty wounded, among them Captain Whinyates. The

Wasp

had five killed and five wounded.

Frolic

’s bowsprit fell between the

Wasp

’s main and mizzen rigging, at which point First Lieutenant James Biddle led a boarding party onto Whinyates’s deck. He found every British officer injured and a sickening number of men killed or wounded. No more than twenty were left to fight. There was nothing Whinyates could do but surrender. In his report to the Admiralty he insisted that had the

Frolic

not been so beaten up in the gale he would have taken the

Wasp

. Jones, of course, would have disputed that. In the end, at least thirty of the

Frolic

’s crew were killed and about fifty wounded, among them Captain Whinyates. The

Wasp

had five killed and five wounded.

Jones’s triumph was short-lived, however. A few hours later, H.M.S.

Poictiers

, a 74-gun ship-of-the-line, under Captain John Beresford, spotted him and made all sail in pursuit, clearing for action as she went. At four o’clock Beresford fired a few warning shots, and Jones struck his colors. The

Wasp

was too beat up from the fight to get away. Beresford took the

Frolic

in tow, and with the

Wasp

and one of the merchantmen in company, he steered for Bermuda.

Poictiers

, a 74-gun ship-of-the-line, under Captain John Beresford, spotted him and made all sail in pursuit, clearing for action as she went. At four o’clock Beresford fired a few warning shots, and Jones struck his colors. The

Wasp

was too beat up from the fight to get away. Beresford took the

Frolic

in tow, and with the

Wasp

and one of the merchantmen in company, he steered for Bermuda.

ON DECEMBER 11, shortly after separating from Rodgers, Commodore Decatur encountered a merchantman who turned out to be an American, the

Mandarin

. She was bound for Philadelphia with a hold full of British goods and a packet of British licenses for use by American traders bringing Pennsylvania grain to Wellington’s army. Decatur put a prize master on board and sent her into Norfolk with instructions to deliver the licenses to Secretary Hamilton. Like all American captains, Decatur found the licensing trade offensive and wished the government would put a stop to it, but for political reasons Madison and the Congress chose not to. By the end of 1812 American farmers were shipping an astonishing 900,000 barrels of grain per year to Wellington.

Mandarin

. She was bound for Philadelphia with a hold full of British goods and a packet of British licenses for use by American traders bringing Pennsylvania grain to Wellington’s army. Decatur put a prize master on board and sent her into Norfolk with instructions to deliver the licenses to Secretary Hamilton. Like all American captains, Decatur found the licensing trade offensive and wished the government would put a stop to it, but for political reasons Madison and the Congress chose not to. By the end of 1812 American farmers were shipping an astonishing 900,000 barrels of grain per year to Wellington.

Two days later, after separating from Arthur Sinclair and the

Argus

, Decatur shaped a course that would take him to a watery highway midway between the Azores and the Cape Verde Islands. Northeast trade winds and ocean currents made this area ideal for stalking British ships traveling to the West Indies, South America, the Cape of Good Hope, the Indian Ocean, the Far East and around Cape Horn to the rich fishing grounds of the Eastern Pacific.

Argus

, Decatur shaped a course that would take him to a watery highway midway between the Azores and the Cape Verde Islands. Northeast trade winds and ocean currents made this area ideal for stalking British ships traveling to the West Indies, South America, the Cape of Good Hope, the Indian Ocean, the Far East and around Cape Horn to the rich fishing grounds of the Eastern Pacific.

Decatur could not have been more pleased. He was right where he had hoped to be when the war started—in command of the

United States

, operating alone, hunting for British warships and for glory. He was the navy’s premier officer, widely known and admired by the public and his peers for his heroic exploits during the war with Tripoli. He was following in the footsteps of his father, Stephen Decatur Sr., who was a naval hero during both the War of Independence and the Quasi-War with France. By coincidence, the

United States

was the first ship young Decatur had served on, coming aboard in 1798 as a nineteen-year-old midshipman during the Quasi-War with France. The Revolutionary War hero John Barry was her captain. Decatur would learn the arts of war and seamanship from Barry and from Lieutenant James Barron, who took a particular liking to him. Even back then, Decatur was a risk taker with an aggressive streak, yearning for adventure and combat. Six years later he would become a national hero when he led the

Intrepid

in her successful mission to destroy the captured American frigate

Philadelphia

in Tripoli harbor. For this amazing exploit President Jefferson promoted him to captain, the highest rank in the service. Decatur was only twenty-five at the time—the youngest man ever to hold the rank of captain in the history of the navy.

United States

, operating alone, hunting for British warships and for glory. He was the navy’s premier officer, widely known and admired by the public and his peers for his heroic exploits during the war with Tripoli. He was following in the footsteps of his father, Stephen Decatur Sr., who was a naval hero during both the War of Independence and the Quasi-War with France. By coincidence, the

United States

was the first ship young Decatur had served on, coming aboard in 1798 as a nineteen-year-old midshipman during the Quasi-War with France. The Revolutionary War hero John Barry was her captain. Decatur would learn the arts of war and seamanship from Barry and from Lieutenant James Barron, who took a particular liking to him. Even back then, Decatur was a risk taker with an aggressive streak, yearning for adventure and combat. Six years later he would become a national hero when he led the

Intrepid

in her successful mission to destroy the captured American frigate

Philadelphia

in Tripoli harbor. For this amazing exploit President Jefferson promoted him to captain, the highest rank in the service. Decatur was only twenty-five at the time—the youngest man ever to hold the rank of captain in the history of the navy.

Other books

In Your Arms by Becky Andrews

The Mystery of a Hansom Cab by Fergus Hume

Ask Me Why I Hurt by Randy Christensen, M.D.

Darke Academy 4: Lost Spirits by Poole, Gabriella

Strange Highways by Dean Koontz

Chloe by Freya North

The Warren Omissions by Jack Patterson

A Promise in Midwinter by Stark, Alyssa

A Plunder of Souls (The Thieftaker Chronicles) by D. B. Jackson

The Evening News by Arthur Hailey