1938 (20 page)

Authors: Giles MacDonogh

Max Schmeling, German prizefighter who failed to clinch the world heavyweight title that year.

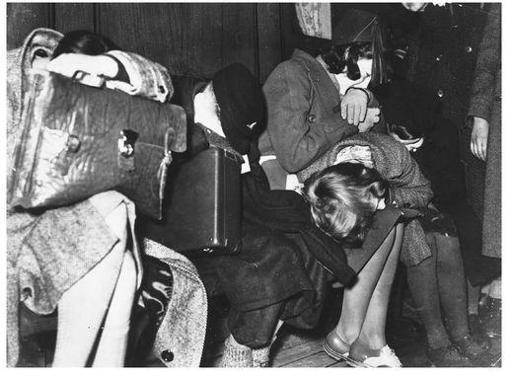

KINDERTRANSPORTE

Members of

Jugendaliya

(Jewish teenagers) leaving the Anhalt Station in Berlin.

Jewish children prepare for a new life, leaving their parents behind.

The half-Jewish dramatist Carl Zuckmayer escaped by the skin of his teeth in March.

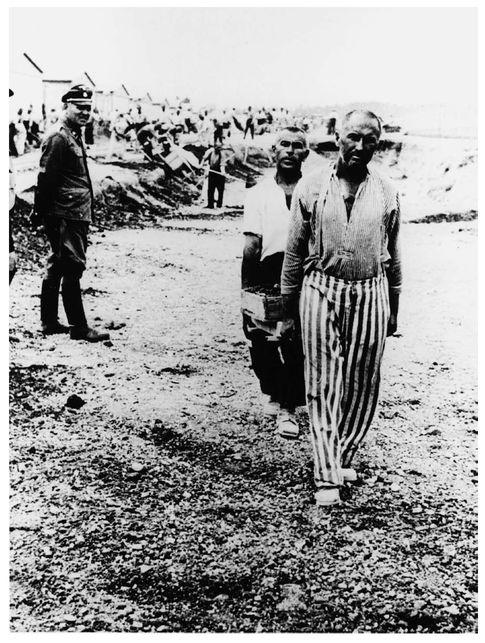

CONCENTRATION CAMPS

Goethe’s oak at Buchenwald—a photograph taken by a French inmate in 1944. The tree was a source of solace for the prisoners.

Political prisoners in Dachau. In 1938 Austria’s governing elite were despatched to the camp.

As the authorities removed the Jews from the food chain, the Viennese began to feel the loss. The central market in the Naschmarkt emptied out. The corn trade was 80 percent Jewish, as well as 31 percent of the leading wine companies. At the time of the harvest that year, a cooperative had to be created to take the place of the old trade. The Hungarians complained that their firms were being closed down too and made a diplomatic protest. When foreign trade began to suffer, Göring started to worry. On October 29, he told the Viennese authorities to slow down.

Hitler turned forty-nine on Wednesday, April 20. His birthday was marked by the usual military parades and a laudation from Göring as well as a special gift from Goebbels—a collection of recordings of his speeches on Austria. Two weeks before, Hitler Youth leader Baldur von Schirach had decreed the Führer’s birthplace, Braunau, to be a place of pilgrimage for young Germans.

Since the death of Paul Ludwig Troost, Albert Speer had become the Führer’s favorite architect. As a present for Hitler’s birthday he was able to bring the plans for the first part of Berlin’s intended great axis, four miles long and flanked by four hundred street lamps. It was to house the principal ministries and part of a crossing of streets that would stretch thirty miles to the east and west and twenty-five to the north and south. Some of the designs—the great dome and the triumphal arch—had been sycophantically worked out from drawings supplied by the Führer himself. For technical reasons, Hitler was of two minds about Berlin as a capital. The city was built on sand, and there was a high water table, requiring the new Chancellery to be constructed on a concrete raft. Hitler had previously wanted to shift the capital to Lake Muritz. On the 24th his ministers had the chance to look over Speer’s building, which was already impressively grandiose.

On the evening of Hitler’s birthday there was a command performance of

Die Meistersinger

conducted by Wilhelm Furtwängler. The Third Reich also celebrated by issuing a warrant for the arrest of Archduke Otto von Habsburg for high treason, while

Der Stürmer

revealed that the first Habsburg had actually been a Jew.

After the festivities, Hitler asked Keitel to adapt the plans for Operation Green, a preemptive strike against Czechoslovakia. Keitel was given the brief to study the Czech system of fortifications. The original blueprint had been drawn up to deal with the eventuality of a Soviet attack on Germany, using their Czech ally as a springboard. Hitler told Keitel there was to be a big opening in the east. The attack had to succeed in four days—the time the French needed to mobilize and come to their ally’s aid.

The German foreign office had been sponsoring ethnic German resistance within Czechoslovakia for the past four years. Now with Ribbentrop in power in the Wilhelmstrasse, there was an even greater desire to see the Czechs embarrassed by the complaints of the Sudetenländer. On this subject, Göring was not the prime mover; he was one of the last to be won round to a Czech adventure. After all, he had given the ambassador, Mastny, his word that Germany would not attack. He pointed out that the defensive West Wall was not ready. It would be the answer to the French Maginot Line, designed to keep the French out if they chose that moment to honor their commitments to the Little Entente. Nevertheless, Hitler convinced him. On April 23 Göring was secretly named Hitler’s successor.

In Karlsbad on April 24, the Sudeten leader Henlein outlined his new eight-point program. The Karlsbad Program called for autonomy for the German regions and German-speaking regiments in the Czech Army. On April 28 Goebbels noted with interest that Prague was looking for security from London and Paris, and that Chamberlain did not appear keen. The British put pressure on Czech President Beneš to accommodate the Sudetenländer, even as it became clear that by honoring Henlein’s requests, he would have destroyed his own state.

In the days leading up to Passover, on April 23 to 26, the spotlight fell on Berlin’s Jews. Their movement was to be curtailed: They were to have one swimming pool and a few restaurants and cinemas but otherwise, Goebbels wrote, “access forbidden. We are going to take away Berlin’s character as a Jewish paradise. . . . The Führer wants to drive them out gradually. He is going to negotiate with the Poles and the Romanians. The best place for them would be Madagascar.” Göring too was turning on the heat in his fight against Jewish capital. “It won’t be long before we floor them,” he wrote.

On the weekend of April 25 and 26, prominent Jews were subjected to unspeakable acts of public degradation in the Prater, a park in Vienna. Kaltenbrunner had made attempts to rein in the SA but with little success. Near the Reichsbrücke over the Danube, Jews were forced to spit in one another’s faces. One who refused died in a concentration camp soon after. In the Taborstrasse in the heavily Jewish Second District, orthodox Jewesses were obliged to remove their wigs and form a parade for the amusement of the Nazi thugs. Jews were strapped into the giant Ferris wheel and spun around at top speed. Jews were forced to run around with their hands up. Others were stripped and beaten by SA men. They had their beards shaved off and were obliged to lick human excrement. The sixty-six-year-old chief rabbi of Vienna was beaten up. On the 26th and 27th twenty-eight Jews committed suicide, including five members of the same family. The Jewish General Sommer appeared on the street in uniform and was made to wash the pavement. In the Aryan Johann-Strauss Café, opposite Gestapo HQ on the Morzinplatz, Jewish regulars were protected by the owner. When the SA came to make the customers clean the streets, the proprietor replied “over my dead body.” The café acted as a welfare center.

The violence was followed by a new edict from the Ministry of the Interior: Jews and Jewish women married to Aryans had to reveal their fortunes of 5,000 RM or above by June 30, whether in the Reich or abroad. In Austria the fortunes of a quarter of the Jews accounted for a sum of 2 billion marks. At the same time, the ministry decreed that its approval was required for all transfers of businesses from Jews to Aryans. The British consul-general Gainer noted bitterly, “It would almost seem as if the manner of their going, whether by the process of emigration to other countries, or by starvation in their own, was of little consequence to those in authority.”

The Zionist Leo Lauterbach wrote to the British Central Bureau for the Settlement of German Jews on April 27. Since the closing of the IKG, the process of emigration had come to a standstill. He had observed in Vienna that the authorities were “bent upon an early evacuation of Austria by the Jews,” but this couldn’t happen without the reopening of Jewish emigration organizations. According to Lauterbach the message had gone home and was voiced in the lines outside the British consulate. He was concerned that the maximum number should reach Palestine and that there were funds to help them.