5000 Year Leap (2 page)

Right now, right this very moment, I want you to make me a promise.

Promise me you will read this book cover to cover in the next 30 days—sooner if you can. Promise me you will pass this book along to somebody else when you’re done. Commit them to read it in 30 days.

Promise me you will write down the 28 ideas and teach them to your children, your neighbors, your friends—Now is the time to get out of our comfort zone.

You, me, all of us were born for this day, to stand responsible before God and future generations to keep this torch of freedom lit, and bear it away from ruin. Twenty failed empires of the past give ample proof that no generation having tasted freedom and then lost it has ever tasted it again.

Do you remember our resolve on September 12, our promise to each other to link arms and face the coming storms together? Those storms are now boiling overhead—our Republic is at stake. You don’t have to be like Washington’s troops and track bloody footprints through the snow at Valley Forge, let’s pray to God we never have to go there again. To fight this battle you need to read, to understand. Learn these 28 ideas, make them your own, put them on the fridge, the bathroom mirror, on your forehead, I don’t care—just know them by heart, that’s all I ask. And yes—there will be a quiz, there’s always a quiz.

Remember those minutemen in the days of our Revolutionary War? Do you remember their job, to be ready to defend the encroachment of the Redcoats with a minute’s notice? If you were called upon to preserve our freedom, to save our Constitution, could you be ready—could you answer in a minute?

I want you to think of this—

One of my favorite Bible stories is Joshua and the battle of Jericho. Remember how they marched around the city and all at once blew their horns and the walls went tumbling down? That’s us all over the place. We are the troops. The truth is our trumpet. And the walls are those same old tired ideas forced on us today—ideas that didn’t work at Jamestown, and certainly won’t work now.

The power is ours to blast our horns and shake those rotted scales off our freedoms, shake them to rubble and get our country back.

Read this book and discover we’re a lot like Joshua—They don’t surround us, we surround Them!

But you’ve got to have your horn ready—now is the time.

Promise me.

—Glenn Beck, March 2009

The Founders' Monumental Task:

Structuring a Government with All Power in the People

What Is Left? What Is Right?

The American Founding Fathers Used a More Accurate Yardstick

Ruler's Law

The Founders' Attraction to People's Law

Characteristics of Anglo-Saxon Common Law or People's Law

The Founders Note the Similarities Between Anglo-Saxon Common Law and the People's Law of Ancient Israel

Memorializing These Two Examples of People's Law on the U.S. Seal

The Founders' Struggle to Establish People's Law in the Balanced Center

The Founders' First Constitution Ends Up Too Close to Anarchy

The Genius of the Constitutional Convention in 1787

A Special Device Employed to Encourage Open Discussion

The Balanced Center

America's Three-Headed Eagle

The Two Wings of the Eagle

Thomas Jefferson Describes the Need for Balance

The Problem of Political Extremists

Jefferson's Conversation with Washington

Jefferson's Concern About the Radical Fringe Element in His Own Party

The Founders Warn Against the Drift Toward the Collectivist Left

The Need for an "Enlightened Electorate"

The Founders' Common Denominator of Basic Beliefs

Fundamental Principles

The Constitutional Convention of 1787

The Constitutional Convention of 1787

Part of the genius of the Founding Fathers was their political spectrum or political frame of reference. It was a yardstick for the measuring of the political power in any particular system of government. They had a much better political yardstick than the one which is generally used today. If the Founders had used the modern yardstick of "Communism on the left" and "Fascism on the right," they never would have found the

balanced center

which they were seeking.

It is extremely unfortunate that the writers on political philosophy today have undertaken to measure various issues in terms of political

parties

instead of political

power

. No doubt the American Founding Fathers would have considered this modern measuring stick most objectionable, even meaningless.

Today, as we mentioned, it is popular in the classroom as well as the press to refer to "Communism on the left," and "Fascism on the right." People and parties are often called "Leftist," or "Rightist." The public do not really understand what they are talking about.

These terms actually refer to the manner in which the various parties are seated in the parliaments of Europe. The radical revolutionaries (usually the Communists) occupy the far left and the military dictatorships (such as the Fascists) are on the far right. Other parties are located in between.

Measuring people and issues in terms of political parties has turned out to be philosophically fallacious if not totally misleading. This is because the platforms or positions of political parties are often superficial and structured on shifting sand. The platform of a political party of one generation can hardly be recognized by the next. Furthermore, Communism and Fascism turned out to be different names for approximately the same thing -- the police state. They are not opposite extremes but, for all practical purposes, are virtually identical.

Government is defined in the dictionary as "a system of ruling or controlling," and therefore the American Founders measured political systems in terms of the amount of coercive power or systematic control which a particular system of government exercises over its people. In other words, the yardstick is not political

parties

, but political

power

.

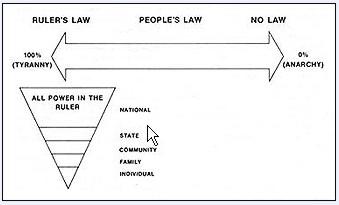

Using this type of yardstick, the American Founders considered the two extremes to be

anarchy

on the one hand, and

tyranny

on the other. At the one extreme of anarchy there is no government, no law, no systematic control and no governmental power, while at the other extreme there is too much control, too much political oppression, too much government. Or, as the Founders called it, "tyranny."

The object of the Founders was to discover the "balanced center" between these two extremes. They recognized that under the chaotic confusion of anarchy there is "no law," whereas at the other extreme the law is totally dominated by the ruling power and is therefore "Ruler's Law." What they wanted to establish was a system of "People's Law," where the government is kept under the control of the people and political power is maintained at the balanced center with enough government to maintain security, justice, and good order, but not enough government to abuse the people.

The Founders' political spectrum might be graphically illustrated as follows:

The Founders seemed anxious that modern man recognize the subversive characteristics of oppressive Ruler's Law which they identified primarily with a tyrannical monarchy. Here are its basic characteristics:

1. Authority under Ruler's Law is nearly always established by force, violence, and conquest.

2. Therefore, all sovereign power is considered to be in the conqueror or his descendants.

3. The people are not equal, but are divided into classes and are all looked upon as "subjects" of the king.

4. The entire country is considered to be the property of the ruler. He speaks of it as his "realm."

5. The thrust of governmental power is from the top down, not from the people upward.

6. The people have no unalienable rights. The "king giveth and the king taketh away."

7. Government is by the whims of men, not by the fixed rule of law which the people need in order to govern their affairs with confidence.

8. The ruler issues edicts which are called "the law." He then interprets the law and enforces it, thus maintaining tyrannical control over the people.

9. Under Ruler's Law, problems are always solved by issuing more edicts or laws, setting up more bureaus, harassing the people with more regulators, and charging the people for these "services" by continually adding to their burden of taxes.

10. Freedom is never looked upon as a viable solution to anything.

11. The long history of Ruler's Law is one of blood and terror, both anciently and in modern times. Under it the people are stratified into an aristocracy of the ruler's retinue while the lot of the common people is one of perpetual poverty, excessive taxation, stringent regulations, and a continuous existence of misery.

In direct contrast to the harsh oppression of Ruler's Law, the Founders, particularly Jefferson, admired the institutes of freedom under People's Law as originally practiced among the Anglo-Saxons. As one authority on Jefferson points out:

"Jefferson's great ambition at that time [1776] was to promote a renaissance of Anglo-Saxon primitive institutions on the new continent. Thus presented, the American Revolution was nothing but the reclamation of the Anglo-Saxon birthright of which the colonists had been deprived by a "long trend of abuses." Nor does it appear that there was anything in this theory which surprised or shocked his contemporaries; Adams apparently did not disapprove of it, and it would be easy to bring in many similar expressions of the same idea in documents of the time."

3

Here are the principal points of People's Law as practiced by the Anglo-Saxons:

4

1. They considered themselves a commonwealth of freemen.

2. All decisions and the selection of leaders had to be with the consent of the people, preferably by full consensus, not just a majority.

3. The laws by which they were governed were considered natural laws given by divine dispensation, and were so well known by the people they did not have to be written down.

4. Power was dispersed among the people and never allowed to concentrate in any one person or group. Even in time of war, the authority granted to the leaders was temporary and the power of the people to remove them was direct and simple.

5. Primary responsibility for resolving problems rested first of all with the individual, then the family, then the tribe or community, then the region, and finally, the nation.

6. They were organized into small, manageable groups where every adult had a voice and a vote. They divided the people into units of ten families who elected a leader; then fifty families who elected a leader; then a hundred families who elected a leader; and then a thousand families who elected a leader.

7. They believed the rights of the individual were considered unalienable and could not be violated without risking the wrath of divine justice as well as civil retribution by the people's judges.

8. The system of justice was structured on the basis of severe punishment unless there was complete reparation to the person who had been wronged. There were only four "crimes" or offenses against the whole people. These were treason, by betraying their own people; cowardice, by refusing to fight or failing to fight courageously; desertion; and homosexuality. These were considered capital offenses. All other offenses required reparation to the person who had been wronged.

9. They always attempted to solve problems on the level where the problem originated. If this was impossible they went no higher than was absolutely necessary to get a remedy. Usually only the most complex problems involving the welfare of the whole people, or a large segment of the people, ever went to the leaders for solution.