5000 Year Leap (5 page)

The Founders also warned that the only way for the nation to prosper was to have equal protection of "rights," and not allow the government to get involved in trying to provide equal distribution of "things." They also warned against the pooling of property as advocated by the proponents of communism. Samuel Adams said they had done everything possible to make the ideas of socialism and communism

unconstitutional

. Said he:

"The Utopian schemes of leveling [re-distribution of the wealth and a community of goods [central ownership of the means of production and distribution], are as visionary and impractical as those which vest all property in the Crown. [These ideas] are arbitrary, despotic, and, in our government, unconstitutional."

17

To prevent the American eagle from tipping toward anarchy on the right, or tyranny on the left, and to see that the American system remained in a firm, fixed position in the balanced center of the political spectrum, the Founders campaigned for a strong program of widespread education. Channels were needed through which the Founders and other leaders could develop and maintain an intelligent, informed electorate.

Jefferson hammered home the necessity for an educated electorate on numerous occasions. Here are some samples:

"If a nation expects to be ignorant and free, in a state of civilization, it expects what never was and never will be."

18

"No other sure foundation can be devised for the preservation of freedom and happiness.... Preach ... a crusade against ignorance; establish and improve the law for educating the common people. Let our countrymen know that the people alone can protect us against these evils [of misgovernment]."

19

What the Founders really wanted was a system of educational communication through which they could transfer their great body of fundamental beliefs based on self evident truths. They knew they had made a great discovery, and they wanted their posterity to maintain it. As Madison said, it is something which "it is incumbent on their successors to improve and perpetuate."

20

One of the most amazing aspects of the American story is that while the nation's founders came from widely divergent backgrounds, their fundamental beliefs were virtually identical. They quarreled bitterly over the most practical plan of implementing those beliefs, but rarely, if ever, disputed about their final objectives or basic convictions.

These men came from several different churches, and some from no churches at all. They ranged in occupation from farmers to presidents of universities. Their social background included everything from wilderness pioneering to the aristocracy of landed estates. Their dialects included everything from the loquacious drawl of South Carolina to the clipped staccato of Yankee New England. Their economic origins included everything from frontier poverty to opulent wealth.

Then how do we explain their remarkable unanimity in fundamental beliefs?

Perhaps the explanation will be found in the fact that they were all remarkably well read, and mostly from the same books. Although the level of their formal training varied from spasmodic doses of home tutoring to the rigorous regimen of Harvard's classical studies, the debates in the Constitutional Convention and the writings of the Founders reflect a far broader knowledge of religious, political, historical, economic, and philosophical studies than would be found in any cross-section of American leaders today.

The thinking of Polybius, Cicero, Thomas Hooker, Coke, Montesquieu, Blackstone, John Locke, and Adam Smith salt-and-peppered their writings and their conversations. They were also careful students of the Bible, especially the Old Testament, and even though some did not belong to any Christian denomination, the teachings of Jesus were held in universal respect and admiration.

Their historical readings included a broad perspective of Greek, Roman, Anglo-Saxon, European, and English history. To this writer, nothing is more remarkable about the early American leaders than their breadth of reading and depth of knowledge concerning the essential elements of sound nation building.

The relative uniformity of fundamental thought shared by these men included strong and unusually well-defined convictions concerning religious principles, political precepts, economic fundamentals, and long-range social goals. On particulars, of course, they quarreled, but when discussing fundamental precepts and ultimate objectives they seemed practically unanimous.

They even had strong criticism of one another as individual personalities, yet admired each other as laborers in the common cause. John Adams, for example, felt a strong personality conflict between himself and Benjamin Franklin and even Thomas Jefferson. Yet Adams' writings are steeped in accolades for both of them, and their writings carried the same for him. One of George Washington's most vehement critics was Dr. Benjamin Rush, and yet that Pennsylvania physician boldly supported everything for which Washington worked and fought.

We will now proceed to carefully examine the 28 major principles on which the American Founders established the first free people in modern times. These are great ideas which provided the intellectual, political, and economic climate for the 5,000-year leap.

The Founder's Basic Principles

Second Principle: A free people cannot survive under a republican constitution unless they remain virtuous and morally strong.

Third Principle: The most promising method of securing a virtuous and morally stable people is to elect virtuous leaders.

Fourth Principle: Without religion the government of a free people cannot be maintained.

Fifth Principle: All things were created by God, therefore upon Him all mankind are equally dependent, and to Him they are equally responsible.

Sixth Principle: All men are created equal.

Seventh Principle: The proper role of government is to protect equal rights, not provide equal things.

Eighth Principle: Men are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights.

Ninth Principle: To protect man's rights, God has revealed certain principles of divine law.

Tenth Principle: The God-given right to govern is vested in the sovereign authority of the whole people.

Eleventh Principle: The majority of the people may alter or abolish a government which has become tyrannical.

Twelfth Principle: The United States of America shall be a republic.

Thirteenth Principle: A constitution should be structured to permanently protect the people from the human frailties of their rulers.

Fourteenth Principle: Life and liberty are secure only so long as the right to property is secure.

Fifteenth Principle: The highest level of prosperity occurs when there is a free-market economy and a minimum of government regulations.

Sixteenth Principle: The government should be separated into three branches -- legislative, executive, and judicial.

Seventeenth Principle: A system of checks and balances should be adopted to prevent the abuse of power.

Eighteenth Principle: The unalienable rights of the people are most likely to be preserved if the principles of government are set forth in a written constitution.

Nineteenth Principle: Only limited and carefully defined powers should be delegated to government, all others being retained in the people.

Twentieth Principle: Efficiency and dispatch require government to operate according to the will of the majority, but constitutional provisions must be made to protect the rights of the minority.

Twenty-First Principle: Strong local self-government is the keystone to preserving human freedom.

Twenty-Second Principle: A free people should be governed by law and not by the whims of men.

Twenty-Third Principle: A free society cannot survive as a republic without a broad program of general education.

Twenty-Fourth Principle: A free people will not survive unless they stay strong.

Twenty-Fifth Principle: "Peace, commerce, and honest friendship with all nations -- entangling alliances with none."

Twenty-Sixth Principle: The core unit which determines the strength of any society is the family; therefore, the government should foster and protect its integrity.

Twenty-Seventh Principle: The burden of debt is as destructive to freedom as subjugation by conquest.

Twenty-Eighth Principle: The United States has a manifest destiny to be an example and a blessing to the entire human race.

and just human relations is Natural Law.

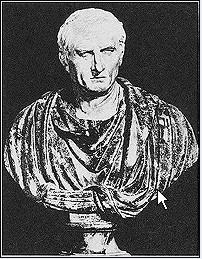

Most modern Americans have never studied Natural Law. They are therefore mystified by the constant reference to Natural Law by the Founding Fathers. Blackstone confirmed the wisdom of the Founders by stating that it is the only reliable basis for a stable society and a system of justice. Then what is Natural Law? A good place to seek out the answer is in the writings of one of the American Founders' favorite authors, Marcus Tullius Cicero.

Cicero's Fundamental Principles

Natural Law Is Eternal and Universal

The Divine Gift of Reason

The First Great Commandment

The Second Great Commandment

All Mankind Can Be Taught God's Law or Virtue

Legislation in Violation of God's Natural Law Is a Scourge To Humanity

All Law Should Be Measured Against God's Law

Cicero's Conclusion

Examples of Natural Law

It was Cicero who cut sharply through the political astigmatism and philosophical errors of both Plato and Aristotle to discover the touchstone for good laws, sound government, and the long-range formula for happy human relations. In the Founders' roster of great political thinkers, Cicero was high on the list.

Dr. William Ebenstein of Princeton says:

"The only Roman political writer who has exercised enduring influence throughout the ages is Cicero (106-43 B.C.).... Cicero studied law in Rome, and philosophy in Athens.... He became the leading lawyer of his time and also rose to the highest office of state [Roman Consul].

"... Yet his life was not free of sadness; only five years after he had held the highest office in Rome, the consulate, he found himself in exile for a year.... Cicero nevertheless showed considerable personal courage in opposing the drift toward dictatorship based on popular support. Caesar was assassinated in 44 B.C., and a year later, in 43 B.C., Cicero was murdered by the henchmen of Antony, a member of the triumvirate set up after Caesar's death."

21

So out of Cicero's maelstrom of turbulent experience with power politics, plus his intense study of all forms of political systems, he wrote his landmark books on the

Republic

and the

Laws

. In these writings Cicero projected the grandeur and promise of some future society based on Natural Law.

The American Founding Fathers obviously shared a profound appreciation of Cicero's dream because they envisioned just such a commonwealth of prosperity and justice for themselves and their posterity. They saw in Cicero's writings the necessary ingredients for their model society which they eventually hoped to build.

To Cicero, the building of a society on principles of Natural Law was nothing more nor less than recognizing and identifying the rules of "right conduct" with the laws of the Supreme Creator of the universe. History demonstrates that even in those nations sometimes described as "pagan" there were sharp, penetrating minds like Cicero's who reasoned their way through the labyrinths of natural phenomena to see behind the cosmic universe, as well as the unfolding of their own lives, the brilliant intelligence of a supreme Designer with an ongoing interest in both human and cosmic affairs.

Cicero's compelling honesty led him to conclude that once the reality of the Creator is clearly identified in the mind, the only intelligent approach to government, justice, and human relations is in terms of the laws which the Supreme Creator has already established. The Creator's order of things is called Natural Law.

A fundamental presupposition of Natural Law is that man's reasoning power is a special dispensation of the Creator and is closely akin to the rational or reasoning power of the Creator himself. In other words, man shares with his Creator this quality of utilizing a rational approach to solving problems, and the reasoning of the mind will generally lead to common-sense conclusions based on what Jefferson called "the laws of Nature and of Nature's God" (The Declaration of Independence).