5000 Year Leap (3 page)

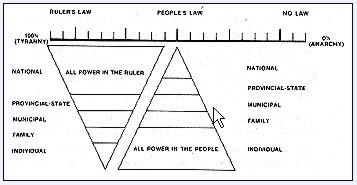

The contrast between Ruler's Law (all power in the ruler) and People's Law (all power in the people) is graphically illustrated below. Note where the power base is located under each of these systems. Also compare the relationship between the individual and the rest of society under these two systems.

and the People's Law of Ancient Israel

As the Founders studied the record of the ancient Israelites they were intrigued by the fact that they also operated under a system of laws remarkably similar to those of the Anglo-Saxons. The two systems were similar both in precept and operational structure. In fact, the Reverend Thomas Hooker wrote the "Fundamental Orders of Connecticut" based on the principles recorded by Moses in the first chapter of Deuteronomy. These "Fundamental Orders" were adopted in 1639 and constituted the first written constitution in modern times. This constitutional charter operated so successfully that it was adopted by Rhode Island. When the English colonies were converted over to independent states, these were the only two states which had constitutional documents which readily adapted themselves to the new order of self-government. All of the other states had to write new constitutions.

Here are the principal characteristics of the People's Law in ancient Israel which were almost identical with those of the Anglo-Saxons:

1. They were set up as a commonwealth of freemen. A basic tenet was: "Proclaim liberty throughout all the land unto all the inhabitants thereof." (Leviticus 25:10)

This inscription appears on the American Liberty Bell.

Whenever the Israelites fell into the temptation to have slaves or bond-servants, they were reprimanded. Around 600 B.C., a divine reprimand was given through Jeremiah: "Ye have not hearkened unto me, in proclaiming liberty every one to his brother, and every man to his neighbor: behold, I proclaim a liberty for you, saith the Lord." (Jeremiah 34:17)

2. All the people were organized into small manageable units where the representative of each family had a voice and a vote. This organizing process was launched after Jethro, the father-in-law of Moses, saw him trying to govern the people under Ruler's Law. (See Exodus 18:13-26.)

When the structure was completed the Israelites were organized as follows:

Moses

V.P. (Aaron) And V.P. (Joshua)

A Senate or Council of 70

A Congress of Elected Representatives

1000 Families

100 Families

50 Families

10 Families

Single family

3. There was specific emphasis on strong, local self-government.

Problems were solved to the greatest possible extent on the level where they originated.

The record says: "The hard causes they brought unto Moses, but every small matter they judged themselves." (Exodus 18:26)

4. The entire code of justice was based primarily on reparation to the victim rather than fines and punishment by the commonwealth. (Reference to this procedure will be found in Exodus, chapters 21 and 22.) The one crime for which no "satisfaction" could be given was first-degree murder. The penalty was death. (See Numbers 35:31.)

5. Leaders were elected and new laws were approved by the common consent of the people. (See 2 Samuel 2:4; 1 Chronicles 29:22; for the rejection of a leader, see 2 Chronicles 10:16; for the approval of new laws, see Exodus 19:8.)

6. Accused persons were presumed to be innocent until proven guilty. Evidence had to be strong enough to remove any question of doubt as to guilt. Borderline cases were decided in favor of the accused and he was released. It was felt that if he were actually guilty, his punishment could be left to the judgment of God in the future life.

It was the original intent of the Founders to have both the ancient Israelites and the Anglo-Saxons represented on the official seal of the United States. The members of the committee were Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and Benjamin Franklin.

They recommended that one side of the seal show the profiles of two Anglo-Saxons representing Hengist and Horsa. These brothers were the first Anglo-Saxons to bring their people to England around 450 A.D. and introduce the institutes of People's Law into the British Isles. On the other side of the seal this committee recommended that there be a portrayal of ancient Israel going through the wilderness led by God's pillar of fire. In this way the Founders hoped to memorialize the two ancient peoples who had practiced People's Law and from whom the Founders had acquired many of their basic ideas for their new commonwealth of freedom.

5

As it turned out, all of this was a little complicated for a small seal, and therefore a more simple design was utilized.

However, here is a modern artist's rendition of the original seal as proposed by Jefferson, Adams, and Franklin.

Artist's version of the original proposal for the American seal

Artist's version of the original proposal for the American seal

Obviously, this is a segment of America's rich heritage of the past which has disappeared from most history books.

In the Federalist Papers, No. 9, Hamilton refers to the "sensations of horror and disgust" which arise when a person studies the histories of those nations that are always "in a state of perpetual vibration between the extremes of tyranny and anarchy."

6

Washington also refers to the human struggle wherein "there is a natural and necessary progression, from the extreme of anarchy to the extreme of tyranny."

7

Franklin noted that "there is a natural inclination in mankind to kingly government." He said it gives people the illusion that somehow a king will establish "equality among citizens; and that they like." Franklin's great fear was that the states would succumb to this gravitational pull toward a strong central government symbolized by a royal establishment. He said: "I am apprehensive, therefore -- perhaps too apprehensive -- that the Government of these States may in future times end in a monarchy. But this catastrophe, I think, may be long delayed, if in our proposed system we do not sow the seeds of contention, faction, and tumult, by making our posts of honor places of profit."

8

The Founders' task was to somehow solve the enigma of the human tendency to rush headlong from anarchy to tyranny -- the very thing which later happened in the French Revolution. How could the American people be constitutionally structured so that they would take a fixed position at the balanced center of the political spectrum and forever maintain a government "of the people, by the people, and for the people," which would not perish from the earth?

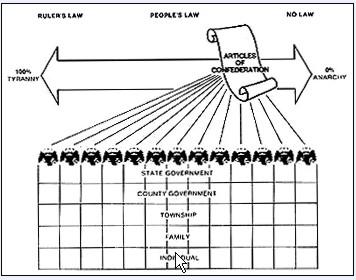

It took the Founding Fathers 180 years (1607 to 1787) to come up with their American formula. In fact, just eleven years before the famous Constitutional Convention at Philadelphia, the Founders wrote a constitution which almost caused them to lose the Revolutionary War. Their first attempt at constitutional writing was called "The Articles of Confederation."

The American Revolutionary War did not commence as a war for independence but was originally designed merely to protect the rights of the people from the arrogant oppression of a tyrannical king. Nevertheless, by the spring of 1776 it was becoming apparent that a complete separation was the only solution.

It is interesting that even before the Declaration of Independence, the Continental Congress appointed a committee on June 11, 1776, to write a constitution. John Dickinson served as chairman of the committee and wrote a draft based on a proposal made by Benjamin Franklin in 1775. However, the states felt that Dickinson's so-called "Articles of Confederation" gave too much power to the central government. They therefore hacked away at the draft until November 15, 1777, when they proclaimed that the new central government would have no powers whatever except those "expressly" authorized by the states. And the states did not expressly authorize much of anything.

Under the Articles of Confederation as finally adopted, there was no executive, no judiciary, no taxing power, and no enforcement power. The national government ended up being little more than a general "Committee of the States." It made recommendations to the states and then prayed they would respond favorably. Very often they did not.

On the Founders' political spectrum the Articles of Confederation would appear as follows:

The suffering and death at Valley Forge and Morristown were an unforgettable demonstration of the abject weakness of the central government and its inability to provide food, clothes, equipment, and manpower for the war. At Valley Forge the common fare for six weeks was flour, water, and salt, mixed together and baked in a skillet -- fire cakes, they were called. Out of approximately 8,000 soldiers, around 3,000 abandoned General Washington and went home. Approximately 200 officers resigned their commissions. Over 2,000 soldiers died of starvation and disease. Washington attributed this near-disaster at Valley Forge to the constitutional weakness of the central government under the Articles of Confederation.

Not one of the Founding Fathers could have come up with the much-needed Constitutional formula by himself, and the delegates who attended the Convention knew it. At that very moment the states were bitterly divided. The Continental dollar was inflated almost out of existence. The economy was deeply depressed, and rioting had broken out. New England had threatened to secede, and both England and Spain were standing close by, ready to snatch up the disUnited States at the first propitious opportunity.

Writing a Constitution under these circumstances was a frightening experience. None of the delegates had expected the Convention to require four tedious months. In fact, within a few weeks many of the delegates, including James Madison, were living on borrowed funds.

From the opening day of the Convention it was known that the brain-storming discussions would require frequent shifting of positions and changing of minds. For this reason the Convention debates were held in secret to avoid public embarrassment as the delegates made concessions, reversed earlier positions, and moved gradually toward some kind of agreement.

To encourage the delegates to freely express themselves without the usual formalities of a convention, the majority of the discussions were conducted in what they called "the Committee of the Whole." This committee consisted of all the members of the Convention, but, as a committee, decisions were always tentative and never binding in the same way they would have been if voted upon by the Convention. Only after a thorough ventilating of the issues would the Committee of the Whole turn themselves back into a sitting of the Convention and formally approve what they had just discussed in the Committee.