A Companion to the History of the Book (87 page)

Read A Companion to the History of the Book Online

Authors: Simon Eliot,Jonathan Rose

The conceit of false spines was to have a glorious future, the titles displaying the owner’s wit and, when they concealed a door, providing a disguised means of escape. By the end of the eighteenth century, the door or pilaster disguised by false spines was common, the false spines having titles that could be satirical

(The Honest Lawyer, The Present State of Morocco)

or puzzling

(Block’s Thoughts

was one at Belton). When the library at Belton was re-sited on the first floor in the 1870s, false spines disguising a door were given titles such as

Canzonetti degli asini, Arte of Deception,

and

Paradise Improved;

more serious titles were

Palanteonis Historia Ocrearum, Leatherhead’s Shakespeare,

and

Epitome of the Trial of Arthur Orton,

this last being a reference to the Tichbourne case of 1874, one of the longest trials in English legal history. An original example dating from the 1770s comes from Antwerp: Francis Adrien van den Bogaert bought the house known as Den Wolsack and had the lavatory decorated entirely with false spines, doubtless to the frustration of occupants accustomed to perusing books when about their easements. In the nineteenth century, the idea was taken up on wallpaper; one of 1889 by the French manufacturer Isidore Leroy provided a variation on the theme, showing a scatter of open and closed volumes by Cervantes, Jules Verne, and Walter Scott. More conventional was a design of 1905–10, recorded at 35 Commonwealth Avenue, Boston, Massachusetts, which shows how an alcove could be converted into a fictive library.

Libraries were a discrete part of well-furbished houses in the eighteenth century, a necessary feature of the stately home in the nineteenth. At what point did contact with books become inescapable? In the early nineteenth century, the designer Humphrey Repton referred to the recent habit of using the library as “the general living room,” the parlor or drawing room being reserved “to give the visitors a formal cold reception.” By 1820, the novelist Maria Edgworth could describe such an environment where books were displayed next to sofas, small tables, and “other means of agreeable occupation” (Edwards 2004: 98). However, Charles Eastlake’s influential work

Hints on Household Taste

(1868) still talks in terms of a separate library, the bookcases proposed (cabinets with shelves above cupboards) following medieval models.

The invasion of books into living spaces was to come later in the century. Houses had to be built in increasingly compact spaces. Collections of books were thrust into living rooms and suitable corners. The

Cabinet Maker

of 1893 proposed a “Library cosy corner” in which books could be stored and presented as part of the arrangement of a larger room. Though the encyclopedic

Book of the Home

(1900) insisted that every home “of moderate size ought to have one room set aside for literary recreation,” it described how books could be stored to decorative advantage in flats. Here, a recess in the dining room, rather than the drawing room, was deemed best to house an escritoire and bookcase. Walsh’s

Manual of Domestic Economy

(1879 edition) assumed that a house run on £1,500 a year had a library, evidently a social space since six chairs were recommended, one on £750 a year a “library or breakfast room,” while on £350 or less books were kept in a chiffonier in a living room. Here was displayed the household’s literary capital.

Just as dust-jackets with attractive colors and designs were used to sell books, so other ways were devised to encourage book buying. The great inventor of the profession of public relations manager, Edward L. Bernays (1891–1995), was commissioned in the 1920s by American publishers to get shelving spaces included in house designs used by speculative builders, so that the rooms would look incomplete unless the eventual owners dashed out to buy books to fill them (Tye 1998: 52). The 1977 play by Mike Leigh,

Abigail’s Party,

shows this in action: as an antidote to his wife’s vulgarity, Laurence draws attention to his set of Shakespeare, “the complete works, a lovely set, embossed in gold, really nice”; it was “part of our heritage, [but of] course not something you can actually read.” A fourteenth-century equivalent is suggested by a group of nearly twenty-five illuminated manuscripts of the

Roman de la rose

decorated by a single team of illuminators in Paris: all have such monumental errors in the placement of initials and rubrics in the text as to suggest that they were never actually read – they were for display. Owners of books like this might have benefited from the service proposed by Myles na Gopaleen (Flann O’Brien) in the 1950s: for a modest sum, works in such libraries would be thumbed, dog-eared, and have inserted bits of theater tickets, tram tickets, and pamphlets as forgotten bookmarks; a “deluxe handling service” wa to include underlining and annotation as evidence of actual use.

The ultimate non-textual use of books is destruction. Today, people find it difficul to get rid of their books. Each represents a memory or act which may have little to d( with the text. In the past, when books went out of fashion, they tended to be destroyed In the first century of printing, university libraries throughout Europe jettisoned manu script books as better printed editions became available. Binders used leaves from dis carded manuscript and printed books to strengthen bindings for some centuries. Theri are records of leaves from manuscript books being used to wrap up groceries and in the Jakes in the sixteenth century (Brownrigg and Smith 2000: 22). Memory of this evi dently lived on. In 1765, Thomas Gray, in his poem “William Shakespeare to Mrs Anne,” suggests that Mrs. Anne steal to a critic’s closet to purloin his notes and usi them as paper for baking and roasting.

Books have traditionally been burnt publicly as a gesture. Reformation Europe sas> much of this as Protestants and Catholics sought to extinguish the memory of eacl other. The Index of the Catholic Church, first instituted in 1559, drove many zealot to pitch forbidden books on the fire. This was the fate of the copy of Eric Cross’s

Th Tailor and Ansty

(1942) owned by the heroes of the story in rural Ireland. Once bannec as obscene by the de Valera government on publication, three priests arrived at thei house to throw their copy on the fire, even though, as Ansty remarked, it was wort! eight shillings and sixpence. Some cities remind us of the consequences of burning books. From 1996, Bebelplatz in Berlin has had a memorial to Nazi burnings of books The Judenplatz in Vienna from 1997 has had a work by Rachel Whiteread as a Holo caust Memorial, a cast of spaces around books on bookshelves, to signify books no written, not read, and not loved by citizens who were Jewish. Whether the symbolii role attributed to books will change as future generations rely on electronic means t( store texts remains to be seen.

References and Further Reading

Brown, T. J. (ed.) (1969)

The Stonyhurst Gospel.

Oxford: Oxford University Press for the Roxburghe Club.

Brownrigg, L. L. and Smith, M. S. (eds.) (2000)

Interpreting and Collecting Fragments of Medieval

Books.

Los Altos Hills: Anderson Lovelace.

Day, V. (2002) “Portrait of a Provincial Artist: Jehan Gillemer, Poitevin Illuminator,”

Gesta,

41 (1): 39–49.

Edwards, C. (2004)

Turning Houses into Homes.

Aldershot: Ashgate.

Kenyon, F. G. (1951)

Books and Readers in Ancient Greece and Rome,

2nd edn. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Leclercq, H. (1951) “Sortes Sanctorum.” In

Dictionnaire d’archéologie chrétienne et de liturgie,

vol. 15, pt. 2, cols. 1590–2. Pans: Letouzey & Ané, 1907–53.

Lewis, B. (ed.) (1965)

Encyclopedia of Islam,

new edn., vol. II. Leiden: E. J. Brill.

Lucas, A. T. (1986) “The Social Role of Relics and Reliquaries in Ancient Ireland,”

Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland,

116: 5–37.

Mayr-Harting, H. (1991)

Ottoman Book Illumination,

2

vols. London: Harvey Miller.

Petrucci, A. (1988) “Biblioteca di Corte e Cultura Libraria nella Napoli Aragonese.” In G. Cavallo (ed.),

Le biblioteche nel mondo antico e médiévale.

Bari: Editori Laterza.

Spurr, J. (2001) “A Profane History of Early Modern Oaths,”

Transactions of the Royal Historical Society,

6th series, 11: 37–63.

Stringer, F. A. (1910)

Oaths and Affirmations,

3rd edn. London: Stevens & Sons.

Thomas, K. (1971)

Religion and the Decline of Magic

London: Wiedenfeld and Nicolson.

Tye, L. (1998)

The Father of Spin: Edward L. Bernays and the Birth of Public Relations.

New York: Crown.

36

The Book as Art

Megan L. Benton

It has covers that open and pages that turn. It appears to be made mostly of paper, and there are words, if not exactly sentences, on many of the pages. But other pages are collaged with bits of old photographs, candy wrappers, and snippets of dried flowers; tendrils of cords and ribbons tumble from the spine; fanciful projectiles bounce from folded springs when a page is turned; and the whole thing fits snugly into an embroidered velvet pouch. Is it a book? Is it art? Is a book still a book when it conveys an artist’s messages more than, or instead of, an author’s?

In today’s art galleries, museums, and libraries, it is not uncommon to come across these intriguing objects, known as

artists’ books,

and to overhear those eagerly whispered, or sadly muttered, questions. Over the past century, and particularly since the 1960s, visual artists have embraced the book as a new medium, treating the page, the object, and the very concept of the book as a vehicle for artistic expression. Many book enthusiasts welcome this lively, often inventive, and provocative activity, believing that it has helped to re-energize interest in the physical book, especially in light of dire predictions of its eclipse by electronic successors. Others scoff, dismissing artists’ books as merely art in the semblance of books’ clothing, not “real” books at all.

Conflicting definitions of both

book

and

art

lurk at the heart of the debate. Some insist that a book is first and foremost a functional object, intended to convey an author’s written text. They welcome books that do so in attractive or appealing ways, but only if such features do not disrupt or compete with that essential textual function. Others believe that a book can bloom into art when it is released from this traditional subservience, when its surfaces and structures reveal an artist’s energies as much as or more than an author’s. “Service to a text” is the sticking point: book purists rarely consider anything a book without it, while art purists tend to scorn anything that attends to it.

The difficulty stems from an old tension between two fundamental aspects of the nature of the book. The word

book

commonly refers both to the linguistic text that an author writes and to the physical object (or electronic presentation) that renders that text visible and so enables us to read it. To distinguish between these two related but neither interchangeable nor inextricable meanings, in this discussion the word

book

refers to the physical package – what we see, touch, and smell as we engage with it as a material object. The word

text

refers to the linguistic messages represented on its surfaces.

This distinction between

text

and

book

is generally clarified as one of content and form. But this is misleading because the material features of books have always been an essential part of their appeal and meaning, and in many instances they have awed, inspired, and moved readers as much as or more than their texts. Often the physical book is not merely a peripheral vehicle for textual content but is an essential element of what we perceive and interpret. Thus the book itself can be a meaningful work of art when its beauty, originality, or other striking or provocative qualities independently engage and affect readers.

This chapter is a selective historical overview (focusing on the Western world) of those books whose impact, significance, or meaning derives from their visual and physical features as much as or more than from their texts. In general, the less a book must accommodate focused, attentive reading, the more freely it may strive instead to engage us as art. Such books-as-art may even forgo conventional text altogether. Modern artists’ books are clearly part of the story. But they are merely the latest development in a long tradition of books notable for the artistry of their visual elements or material form.

From the earliest forms of what we now call books, art has often been an integral part of their making. Before the fifteenth century, the power and significance of books commonly rested as much in their tactile and visual qualities as in their texts. They often held great iconic significance, in part because they were rare and costly objects, and because the ability to read their texts was even rarer. Particularly when the texts were sacred or religious in nature, as most were, those fortunate enough to see books at all often simply viewed them, perceiving them as precious objects imbued with the mysterious, sacred qualities of their texts. At times, the scribes and artists who created the pages lavished them with an extravagance of color, gilt, design, and imagery that awed and humbled those who beheld them. Such books were primarily visual objects, crafted into virtual icons of the abstract texts they bore.

By the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, books began to serve more secular purposes. While still largely sacred objects, they increasingly became the prized property of fortunate individuals, not just of religious communities, signaling the wealth, power, and piety of their owner as well as the exalted status of their texts. Among the best examples of this late medieval infusion of visual beauty and power into bookmaking are the personal devotional aids known as Books of Hours. Because they were usually made to order, Books of Hours sometimes incorporated remarkably revealing visual information about the person for whom the book was commissioned. The owner might be discreetly depicted worshiping a patron saint, for example, or witnessing a familiar biblical scene. In this way, medieval Books of Hours are early ancestors of contemporary one-of-a-kind artists’ books that also embed uniquely personal content within the more public.

The fifteenth century marked a major turning point in the history of books as art, involving three related factors. First, the visual and aesthetic character of the page changed, slowly at first and then dramatically, as the new printing process pioneered by Johann Gutenberg replaced unique, hand-produced pages with more or less identical, mechanically rendered multiples. Secondly, growing humanist interests in science, philosophy, law, literature, and other secular knowledge, coupled with the increasing accessibility of books spurred by printing, stimulated the spread of literacy, though it was still limited to a small portion of the population. Thirdly, Renaissance societies came to view art as the expressive achievement of a creative individual, breaking from the medieval belief that the artist was merely an anonymous craftsman. Together, these developments shifted the predominant nature of books from visual to textual.

In the following centuries, the primacy of the text grew so pronounced that images, decoration, and other aesthetic enhancements were often scorned, for a variety of reasons that remain potent to this day. Some considered them simply superfluous, “visual aids” no longer needed and even somewhat demeaning when readers could actually read the texts. Bolstered by the new Protestant emphasis on personal Bible reading, others regarded images warily as rivals for readers’ attention, distracting them or (worse) contradicting, distorting, or oversimplifying the text’s message. Still others appreciated the value of occasionally illustrating or adorning a book, but balked at considering that work as art, since such embellishments were clearly subordinate to the book’s text.

Despite this new resistance to art in books, there continued to be books made with exquisite artistry, although their numbers were dwarfed by the great majority of books produced with an emphasis on economy, efficiency, and utility. Books-as-art can be divided into two categories: those that feature notable artistry in their making, and those with exemplary artwork on their pages.

As the first printed books began to make their way into readers’ hands, many were skeptical that they could match the beauty of manuscript books. What was gained in economy and quantity was lost, they lamented, in visual quality. Many of these fears were reasonable: the need to produce books quickly and relatively cheaply (pressures stemming from the printers’ precarious finances as well as from growing market demands) quickly forced several compromises in the printers’ original aims to recreate the look of manuscript books as closely as possible.

Most immediately striking was the loss of color. Because each color had to be printed separately, to replicate the traditional red and blue initials and other colorful features of manuscript pages would have dramatically multiplied production costs. The earliest printers simply printed the text and left blank spaces where the color initials would go, intending to subcontract a scribe or artist to complete the pages, just as he would have completed a manuscript page. Very shortly, however, printers dispensed with this cumbersome (and often never completed) practice, instead hiring engravers to cut relief wood blocks of the decorative initials, which could be inked and printed in black ink like type. Yet much was gained as well as lost with this shift. While manuscripts had usually been decorated on only a small number of pages, printers could use woodcuts to print intricate borders, initials, and illustrations on virtually any page – or all pages – because, like type, woodcuts could be used repeatedly. In fact, many early modern editions seem profligate in their use of woodcut images, even reusing the same cut to illustrate different subjects. One German printer, Conrad Dinckmut of Ulm, repeated a full-page depiction of “torments of the damned” more than thirty times in a profusely illustrated edition of the

Seelenwurzgarten.

As it quickly became apparent that printing could only approximate, not truly replicate, the centuries-old bookmaking handcrafts of calligraphy and illumination, a new aesthetic of bookmaking emerged, based on the new skills required for printing: type design, typography, and woodcut or engraved imagery and decoration. At the same time, Renaissance sensibilities drove bookmaking aesthetic values in new directions. Printing had originated in Germany, where the medieval letterforms known generically as blackletter prevailed. By the 1460s, printers in Italy, eager to publish new classical and humanist texts but loath to present them in these Gothic forms tainted with “barbaric” medieval associations, pioneered new types based on the letterforms of classical Rome and the eighth-century reign of Charlemagne, and hence called

roman.

A Frenchman living in Venice, Nicholas Jenson, is usually credited with producing the first enduringly fine roman types, which he premiered in 1470 to wide acclaim. Accompanied from about 1500 by a cursive Renaissance letterform called

italic,

roman type soon became the new foundation for typographic beauty in Italy and much of Europe.

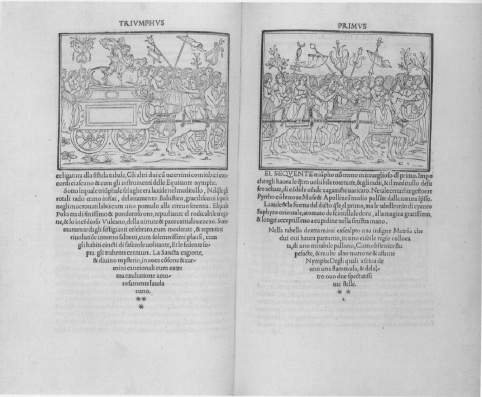

The foremost typographic master of the Renaissance was the Venetian printer Aldus Manutius. The elegance, clarity, and refinement of his roman and italic types and his typographic layout demonstrate that, within the first half-century after Gutenberg, the book had already achieved a new, essentially modern look, deemed particularly appropriate for humanist and classical texts. Although Aldus is primarily remembered for the intelligent dignity and beauty of serious works of scholarship, his most famous work is anomalous, an illustrated work of fiction: his 1499 edition of

Hypnerotomachia Poliphili

(the love-dream of Poliphilus), often touted as the most beautiful book ever printed (

figure 36.1

). It features the stately roman types of Francesco Griffo, sculptural arrangements of type columns, sometimes tapering to a V-shape, and liberal yet judicious use of type ornaments or fleurons (printers’ flowers). The book is also generously illustrated by an unnamed artist with 170 woodcuts rich with both narrative content and classical ornament.

In the sixteenth century, the greatest achievements in bookmaking artistry came from France, where Geoffrey Tory and Claude Garamond designed graceful new Renaissance types. Premier publishers Simon de Colines and the Estienne family similarly continued and refined Aldus’ pursuit of a typographic ideal grounded in the pure beauty of type and careful symmetry, proportion, and balance in the arrangement of the printed page. As in other matters of culture and the arts, the French, and to a lesser degree the Dutch, dominated European book artistry in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. Baroque books, however, featured opulent title pages engraved in copperplate and were dense with exquisitely detailed ornamental imagery and ornate calligraphic lettering. They were followed by a lighter, more delicate rococo style in both type design and ornamentation. In the 1760s, Pierre-Simon Fournier’s elegant types, fleurons, and decorative borders epitomized the highly cultivated aesthetic values of the era (

figure 36.2

). Between 1745 and 1772 the French book reached what many regard as its zenith with the appearance of

L’Encyclopédie,

the crowning achievement of Enlightenment scholarship and thought. It was equally impressive as a visual masterpiece: eleven of its twenty-eight folio volumes were devoted to nearly three thousand scrupulously detailed engraved illustrations, comprising an unsurpassed portrait of eighteenth-century life, especially its technology.

Figure 36.1

Francesco Colorína,

Hypnerotomachia Poliphili

(Venice: Aldus Manutius, 1499).