A Companion to the History of the Book (89 page)

Read A Companion to the History of the Book Online

Authors: Simon Eliot,Jonathan Rose

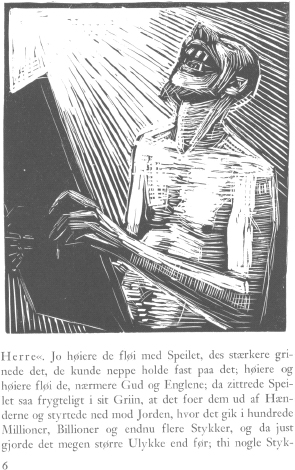

Although initially more focused on type and typography, the Anglo-American fine-printing movement soon showcased masterful illustration as well. In keeping with its revivalist spirit, most artists returned to woodcuts and wood engravings, the earliest techniques of printing images. Artists such as Rockwell Kent in the United States and Eric Gill, Blair Hughes-Stanton, and Claire Leighton in Britain produced exquisite illustrations for finely printed, deluxe limited editions. Less well-known artists in other countries offered equally fine but more accessible examples of the wood-engraving renaissance: Denmark’s Jane Muus and Povl Christensen, for instance, illustrated several moderately priced editions of Danish literary works throughout the 1940s and 1950s (

figure 36.4

).

The practice of producing handsome editions that pair important literary texts and original artwork by leading contemporary artists has continued, albeit usually for well-heeled collectors. Andrew Hoyem’s Arion Press in San Francisco has published such major works as the King James’s Version of

The Apocalypse,

with woodcuts by Jim Dine (1982), and James Joyce’s

Ulysses,

illustrated by Robert Motherwell (1988).

These examples all feature art that is explicitly paired with, while not strictly subordinated to, a literary text by a printer or publisher. Beginning with the extraordinary work of William Blake in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, artists themselves have turned to the book as a medium in which they could fuse visual, linguistic, and formal elements into their own coherent artistic vision. Blake’s achievement was so original and all-encompassing that it nearly defies description. A skillful engraver by trade, Blake modified the process to produce copies of his own poems and illustrations. He developed a mysterious, hybrid printmaking process which he called relief etching, rendering plates from which he could print an entire page, both drawn images and handwritten text. After printing each plate in a small edition, Blake and his wife water-colored and assembled the sheets into books, one at a time by hand, as prospects of a buyer occurred. Because he controlled every aspect of the book’s creation, from concept to execution, each unique book fairly bursts with artistic “aura.”

Few subsequent artists have replicated Blake’s feat of personally producing every element of the book, from text to images to completed final pages, but he has inspired many to undertake a much broader role than illustrators have traditionally played. In the early decades of the twentieth century, for example, François-Louis Schmied designed, illustrated, and supervised the elaborate production of several deluxe editions. The stunning decorative detail, rich colors, and sensual subject matter of his

pochoir

(stencil) illustrations, integrated through the books with Schmied’s own ornaments and borders and deft typography, make his works landmark examples of the lavish art deco book in France. Even more pervasive was Henri Matisse’s hand in the production

oí Jazz

in 1947. Matisse wrote the text to “interrupt” his colorful paper-cut images, reproduced with stencils, and the text is printed from Matisse’s own calligraphy. American wood engraver Barry Moser offers a notable contemporary example: under his Pennyroyal Press imprint, Moser has published editions of such literary classics as

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

’(1982) and

Frankenstein

(1984), accompanied by his haunting and powerful illustrations. To the delight of thousands of book lovers, several of Moser’s productions have been reproduced in affordable trade facsimile editions.

Figure 36.4

H. C. Andersen,

Sneedronningen [The Ice Queen]

(Copenhagen: Nordlundes Bogtrykkeri, 1959). Designed by C. Volmer Nordlunde, with illustrations by Jane Muus.

While much of the most prestigious art in books has been reserved for costly deluxe editions, modern trade publishing also offers notable examples of books whose power derives from art as much as or more than from text. In the 1920s and 1930s, Belgian Franz Masereel and American Lynd Ward produced the first so-called woodcut novels, which are entirely image-based. Through a series of 139 dramatic woodcuts without captions or narrative text, Ward’s most famous work,

God’s Man

(1929), tells the poignant tale of a young artist’s tragic encounters with modern urban corruption. More recent examples include graphic novels such as the 1986 trade book

Maus: A Survivor’s Tale,

in which Art Speigelman used the comic strip narrative model to express his father’s Holocaust experience. Similarly adapting image-narrative techniques associated with children’s books, Canadian writer–artist Nick Bantock created visually saturated pages and interactive reading for his novel about the mysterious relationship between

Griffin and Sabine

(1991): the texts are read through a series of exchanged postcards and letters, printed separately and inserted in envelopes on the book’s pages.

As these two contemporary examples suggest, modern children’s books have generally been much more visually imaginative and innovative than books for adults. Beatrix Potter and Kate Greenaway produced stories told as memorably through their illustrations as through their prose. In the twentieth century, several artists have sustained and deepened this mode of complete integration: Maurice Sendak, Chris Van Alsberg, and David Weisner immerse readers in compelling visual environments that adults often find as irresistible as children do.

The strongest evidence of an increasingly visual aesthetic in modern bookmaking is the burgeoning interest in artists’ books. Although definitions are slippery and inevitably contested, Johanna Drucker, a leading critic as well as a practitioner of the genre, distinguishes an artist’s book from its cousins the illustrated book and the

livre d’artiste

by its provocative challenge of our preconceptions, by the ways in which it “interrogates the conceptual or material form of the book as part of its intention, thematic interests, or production activities” (1995: 3). In

The Century of Artists’ Books,

Drucker usefully surveys a broad spectrum of works functioning as an “auratic object,” a “democratic multiple,” and an “agent of social change.”

As those categories suggest, an artist’s book may be a one-of-a-kind construction, perhaps featuring original drawings or paintings and commanding a lofty price, or it could be an inexpensive photocopied pamphlet reproduced by the hundreds and distributed for little or no charge. Both extremes testify to the range of artists’ attractions to the book form in the twentieth century. Some see it as an affordable means of extending art beyond the galleries and into everyday lives, often carrying powerful political and social messages. Others see the book as a supremely multilayered medium, combining opportunities for simultaneous literary, visual, sculptural, kinetic, and sequential expression. For all book artists, however, the book itself, as a whole, comprises its identity as art; each element – text (if any), imagery (if any), form, and structure – contributes to the work’s meaning.

Among the first artists heralded for adopting the book as a vehicle for art was American Ed Ruscha, whose 1962

Twenty-six Gasoline Stations

is often placed at the forefront of the new movement. The book consists of twenty-six black-and-white photographs of gasoline stations, in all their stark banality. Unlike a trade art book that features reproductions of works actually in galleries or private collections, Ruscha’s book itself – its selection, sequence, and presentation of images – is the work of art.

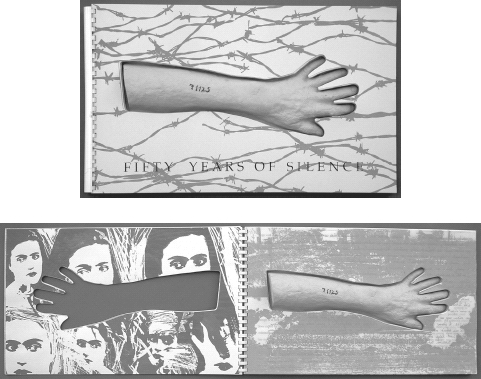

Figure 36.5

Tatana Kellner,

71125: Fifty Years of Silence

(Rosendale: Women’s Studio Workshop, 1992). Designed, illustrated, and produced by Tatana Kellner.

Also in the 1960s, British artist Tom Phillips began work on another ground-breaking, highly influential artist’s book,

A Humument.

By painting over large portions of the pages of the 1892 novel

A Human Document,

leaving legible only a few phrases, words, or parts of words, Phillips foregrounded a disruptive, partial, and hence “new” text embedded in fully visual fields rather than displayed in conventional blocks of print surrounded by white margins. This technique of creating “altered books” has opened up a popular and provocative new field of activity, blending at times with the interest in affixing images, texts, and objects to existing pages, scrapbook-style, in order to create a unique book expressing the subjective vision of the artist.

Artists’ books offer a particularly rich venue for highly personal content; many of the most moving works are in this vein. For example, Tatana Kellner’s

71125: Fifty Years of Silence

(1992) tells the story, through text printed over and wrapped around images, of her mother’s reluctance or inability to speak of her experiences in a German concentration camp (

figure 36.5

). Each wide page is die-cut to fit around a life-size cast of a woman’s forearm, stamped with a number, protruding from the book’s back through its front cover. As a reader moves through the book, the arm remains as a fixed, three-dimensional presence embedded within each recto page, while each verso page is dominated by the arm-shaped hole in its center. As with all successful artists’ books, one reads the material object as much as the text printed on its pages.

Other artists explore the book as a purely visual, kinetic, and sculptural medium. These books’ meanings reside fully in their materials, forms, and action. Among the most famous examples is Keith Smith’s

Book No. 91

(1982), commonly known as his String Book because it consists of series of strings woven through small holes in the thick paper pages of a traditional codex. The strings intersect, drape, and pull as the pages are turned, producing changing patterns of sliding sound and spokes of shadow, animating the work’s tension and slippage. Fascinated with books’ structural possibilities, Smith has explored dozens of historically and ethnically diverse binding styles and invented as many more. Through his prolific work, incorporating accordion folds, scrolls, containers, fans, codexes, and more, he has demonstrated the myriad ways in which form and material alone can invite thoughtful encounters.

The most important intent of this brief survey is to suggest the great scope of art in books. While only a small number of books might register as works of art

per se,

in a larger sense all books are intrinsically visual and sculptural objects, no matter how much those qualities are obscured by convention and familiarity. As we become more aware of the rich, aesthetic powers of the book itself, beyond those of its text, our experiences as readers can only grow more full and meaningful.

References and Further Reading

Benjamin, Walter (1969) “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” In

Illuminations,

ed. Hannah Arendt, trans. Harry Zohn, pp. 217-51. New York: Schocken.

Bettley, James (ed.) (2001)

The Art of the Book: From Medieval Manuscript to Graphic Novel

London: V&A.

Bland, David (1969)

A History of Book Illustration: The Illuminated Manuscript and the Printed Book,

2nd edn. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Camille, Michael (1992)

Image on the Edge: The Margins of Medieval Art.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Drucker, Johanna (1995)

The Century of Artists’ Books.

New York: Granary

de Hamel, Christopher (1994)

A History of Illuminated Manuscripts.

London: Phaidon.

Harthan, John P. (1981)

The History of the Illustrated

Book: The Western Tradition.

London: Thames & Hudson.

Hogben, Carol and Watson, Rowan (eds.) (1985)

From Manet to Hockney: Modern Artists’ Illustrated Books.

London: V&A.

Katz, Bill (ed.) (1994)

A History of Book Illustration: 29 Points of View.

Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow.

Levarie, Norma (1968)

The Art and History of Books.

New York: Heinemann.

Lewis, John (1984)

The Twentieth-century Book: Its Illustration and Design,

2nd edn. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.