A History of China (28 page)

Read A History of China Online

Authors: Morris Rossabi

An even greater indication of this conjunction was the development of landscape painting. Hardly any of these early paintings have survived, but several attributed to or in the style of Gu Kaizhi (344–406) have been transmitted. Gu Kaizhi’s depictions of mountains, trees, and rivers reveal the same concerns with serenity found in the Daoist poetry. Records about other landscape painters whose paintings have not lasted into modern times indicate that they shared a similar interest in landscapes.

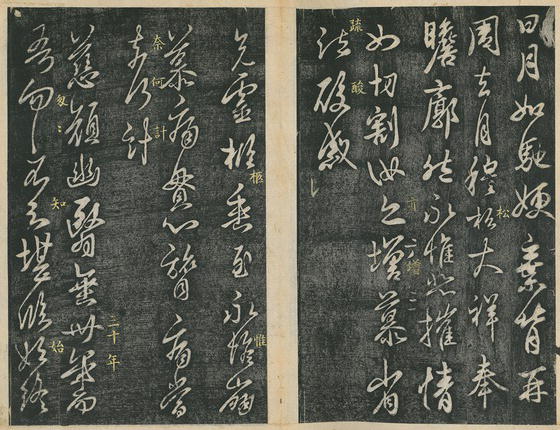

Calligraphy as an art form developed during this era, though precious few examples have survived. The works of the great calligrapher Wang Xizhi (303–361) reveal a relaxation from the more formal style of

lishu

(clerical script) to

caoshu

(grass script), which permitted greater experimentation, creativity, and individuality – all traits that conformed to the Daoist precepts that dominated the art world.

Figure 4.2

Leaves seven and eight from Wang Xizhi Book One, “Calligraphy of Ancient Masters of Various Periods,” Section V of the “Calligraphy Compendium of the Chunhua Era,” 1616, ink rubbing and yellow ink on paper, Chinese School, Ming dynasty (1368–1644). © FuZhai Archive / The Bridgeman Art Library

The greatest concentration of surviving artworks are of Buddhist origin. They were found particularly in the Yungang, Longmen, and Dunhuang caves but also in other Buddhist sites in Binglingsi (about fifty miles along the Yellow River from Lanzhou) and in Maijishan (in the modern province of Gansu). The early sculptures in these caves were massive, heavy, and austere and reflected Indian and central Asian influences, but the later sculptures were refined and lighter, with flowing robes and with more human faces. The Dunhuang paintings (in their 492 caves), which survived owing to the dry climate in the desert regions surrounding the Dunhuang oasis, often provide vignettes of the Buddha’s life; depict different emanations of the Buddha, bodhisattvas, and

apsaras

(flying figures, often of musicians); and illustrate tales concerning the Buddha’s earlier incarnations in the form of animals. These charming frescoes, which originally consisted principally of Indian subjects and motifs, became increasingly Chinese in themes and styles.

Loosening of strict aesthetic standards and greater opportunities for individuality and creativity characterized the culture of this politically unstable period. Daoist poets deviated from established patterns in order to express their individual reactions to nature and their desire for a mystical union with all phenomena. Painters produced images that displayed their own feelings toward the landscape rather than stereotyped societal attitudes, and even painters of Buddhist themes and motifs sought to deviate from central Asian and Indian models and to create their own individual styles. Like the painters of Buddhist subjects, the sculptors who created images derived originally from the Indian religions began to introduce innovations on the acceptable mode of depiction. Non-Buddhist sculpture, particularly figures of humans and animals adjacent or leading to the tombs of emperors or prominent nobles along a so-called spirit road leading to the main burial site, also revealed a less stereotyped and more individual portrayal of secular figures.

All sorts of discoveries and innovations in techniques and practices developed, partly as a result of the experiments and activities related to Buddhism and Daoism and partly from the exposure to the outside world afforded by Buddhism. The burning of incense for ceremonial and religious purposes and the chanting of mantras that evolved into music became popular practices that had Buddhist origins. The translations of Buddhist writings into Chinese led to the development of dictionaries and grammars. Daoist attempts to prolong life resulted in experiments with alchemy and chemistry, which often brought with them valuable discoveries. Knowledge of a variety of specific herbs, metals, other elements, and chemical reactions increased. These discoveries contributed not only to medicine but also to technology and perhaps to science, or at least to an inquisitive attitude and a desire for additional knowledge of the physical world.

With their concern with helping the afflicted and ailing, Buddhists also contributed to medical discoveries and insights. Indian medicinal recipes reached China; a Buddhist text that offered descriptions of hundreds of ailments was translated into Chinese. Another Buddhist text described diseases of the eyes, ears, and feet. Several monks reputedly performed miracle cures, which permitted a paralytic to regain use of his limbs and stemmed an unspecified epidemic. These remarkable occurrences did not, in themselves, produce medical breakthroughs; nonetheless, they indicated interest in and support for efforts to cater to the ills of mankind. Amelioration of the ailments of the body became part of the Buddhist mission, no doubt spurring experimentation and advances in medicine.

Despite the evident breakdown of the old society, scholarship and cultural developments proceeded apace, in part abetted by the arrival of influences and individuals from abroad. Indian and central Asian Buddhists introduced not only the tenets of the religion and the attendant art and architecture but also innovations in other cultural areas – music, for example. Complementing the music meant to accompany Buddhist rituals and ceremonies was the secular music of the nomadic and oasis peoples of central Asia and Mongolia, to which north China was exposed with the establishment of non-Chinese dynasties there. The scriptures and paintings in the Buddhist caves depict orchestras with both Chinese and foreign instruments. The

sheng

(a blown reed instrument) and the

pipa

(or lute) had been known in China before this time, but the

suona

(a kind of oboe) and the harp had been imported, probably via central Asia, from Persia.

The southern Kingdom of Wu, one of the successor states to the Han, contributed to Chinese scholarship through its foreign contacts. Because of its position in the south, Wu and its rulers became increasingly involved with areas in Southeast Asia. They exchanged envoys with the Kingdom of Funan (roughly modern Cambodia), and Wu ambassadors returned from these journeys with invaluable information, increasing China’s familiarity with the geography, customs, and accomplishments of some of the Southeast Asian peoples. Among the more important observations of one account concerns the scope of seaborne commerce conducted at this time, the sailors’ knowledge of optimal trade routes, and the information about the spread of Indian religions. The size of some of the vessels that plied these trade routes is surprising. One perhaps exaggerated account indicates that junks could transport as many as five or six hundred men.

The greater contact between China and its neighbors in the south and north compelled an interest in geography and, in particular, cartography. A government official named Pei Xiu (224–271) produced a now lost map of China that delineated the various provinces and located the mountains, seas, and towns. This map, based on a grid system, spurred interest in cartography and served as one of the models for future mapmaking. A side effect of this interest was the compilation of local histories or gazetteers, the first of which provided information on the products, customs, flora and fauna, and meritorious men from the region of modern southern Shaanxi and northern Sichuan. Many provinces, districts, counties, and other local regions adopted the practice of collecting information and writing about their Buddhist and Daoist temples and monasteries, flood-control projects, prominent buildings and monuments, taxes, academies and schools, and trade, as well as compiling biographical sketches of leading individuals. Local governments often commissioned these collections but sometimes local scholars, as a leisurely diversion, contributed and produced these works, which often served as handbooks for officials unfamiliar with the local areas to which they were assigned. Thousands of these gazetteers have survived into modern times and offer a mine of information about Chinese history.

These advances in knowledge exemplify the remarkable innovations of this seemingly chaotic period in Chinese political history. Paradoxically, this era of turbulence witnessed the introduction of invaluable cultural contributions to China. Yet this period was not unique, for previously chaotic ages (e.g. the Warring States era of the Zhou dynasty) saw remarkable achievements in Chinese philosophy. Unstable political and economic conditions appear, on occasion, to have stimulated experiments and attempts to find underlying shared views that might facilitate unity and defuse the unsettled and violent environment. A centralized government was not essential for cultural developments and innovations. Vital changes could and did take place in times of unrest.

Thus, despite the turbulence, individual Chinese invented important devices and discovered new techniques or objects. The wheelbarrow, invented at this time, facilitated the peasants’ work by permitting the transport of humans and animals more readily and with less labor and effort. The watermill also lightened the peasants’ burdens by offering a simpler method of irrigating the land and grinding grain. Sedan chairs, which may have been used initially to carry the elderly and ailing, first came into prominence during this period. Within a short time, they became status symbols, as the elite appropriated them as a means of transport. The bleakness of the era may have spurred interest in games as distractions. Backgammon and elephant chess diverted many Chinese, and books on chess began to appear in the sixth century. Chinese flew kites as recreation and for practical effects as well. On one extraordinary occasion, an emperor, whose capital was besieged by the enemy, sought assistance by sending a kite aloft to inform allies of the perils he faced.

Perhaps less frivolous and of more consequence were the introduction of new plants and the discovery of uses for minerals. The new agricultural goods, several of which originated abroad, included onions, sesame, pomegranates, safflower, and broad beans, all of which enriched the Chinese diet and cuisine. However, the most influential discovery was tea, a beverage that would have profound effects on Chinese art and literature and on its economy. The first records of tea derive from the third century, though it may have been consumed earlier. Its use stems from the migration to south China, which had the proper soil for its growth. Tea was later associated with Buddhist ceremonies and became an integral part of such rituals. Throughout history, Chinese attributed wondrous benefits to tea drinking, including cures that cannot be proven. However, tea was valuable because it offered the benefits of boiled water, as opposed to impure and sometimes polluted water.

The use of coal to smelt iron and for fuel dates from this era as well, although a few references appear to point to an earlier origin. This discovery preceded by about a thousand years the application of coal for the same purpose in the West and averted the denuding of China’s forests. Much of the remainder of China’s timberland was nonetheless ravaged, but the damage would surely have been more widespread without the hot ember. The relative paucity of trees in parts of north China necessitated the tapping of another resource for fuel.

In sum, this period of disunion and the attendant often chaotic conditions did not preclude cultural, scientific, and economic developments. Many Chinese profited from the technological advances and foreign imports during this era. As in the Warring States period, political chaos and dynastic changes did not necessarily relate to social and cultural developments. Political stability was not essential for agricultural and economic growth. Neither was it vital for an efflorescent cultural and social life. Political chaos resulted from the lack of a central government capable of unifying the country. Local aristocrats contested efforts at centralization, and the various dynasties in both north and south China did not have the power or the policies needed to overcome such resistance. Also, ordinary Chinese who remembered the instability, corruption, and mismanagement of the Later Han dynasty may have been wary of supporting a powerful central government. Only when the lack of a central government fostered extraordinary unrest did common people recognize the desirability of a government to regulate society and to restore stability.

OTES

1

Clarence Hamilton,

Buddhism: A Religion of Infinite Compassion

(New York: Bobbs-Merrill, 1952), pp. 3–4.

URTHER

R

EADING

Albert Dien,

Six Dynasties Civilization

(New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007).

Jacques Gernet,

Buddhism in Chinese Society: An Economic History from the 5th to the 10th Centuries

, trans. by Francois Verellen (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995).

Liu Xinru,

Ancient India and Ancient China: Trade and Religious Exchanges, AD 1–600

(Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1988).

James Watt et al.,

China: Dawn of a Golden Age, 200–750 AD

(New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2004).

Arthur Wright,

Buddhism in Chinese History

(Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1959).