A History of China (24 page)

Read A History of China Online

Authors: Morris Rossabi

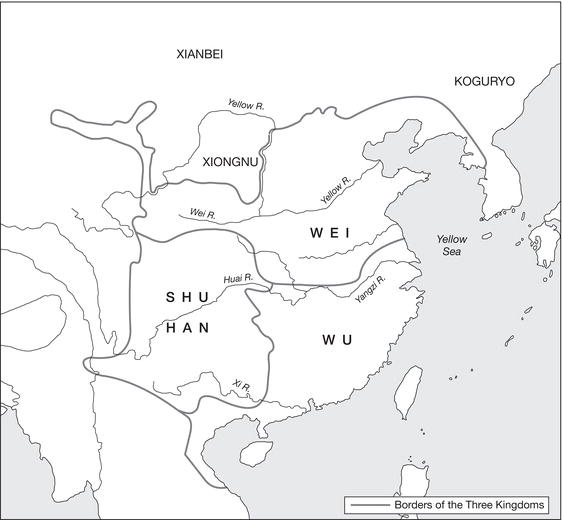

Map 4.1

The Three Kingdoms

Chinese accounts later romanticized this era’s warfare. Contemporaries, however, confronted chaotic conditions. Nonetheless, the romantic versions were eventually gathered together and compiled into an episodic, lengthy, and popular fourteenth-century novel, the

Sanguozhi yanyi

(

The Romance of the Three Kingdoms

), by Luo Guanzhong (ca. 1330–1400). Because these later accounts embroidered upon the stories of this era’s commanders and strategists, the military leaders became legendary heroes. The Shu Han kingdom perhaps provided the most important heroes. Liu Bei became portrayed as a benevolent sage in the Confucian tradition and was worshipped, specifically in the city of Chengdu in Sichuan. His leading general, Guan Yu (d. 219), depicted as red-faced with a long beard, was transformed in folk religion to Guan Di, the God of War, a subduer of demons in the Daoist pantheon and an important figure in Buddhism. Similarly, the brilliant tactician Zhuge Liang (181–234) was idealized as the military genius par excellence. They have continued their hold on the Chinese through portrayals in temples, operas, films, television, and restaurants, and even in card and video games.

Each kingdom initially expanded its territory but then faltered. Shu Han overwhelmed the groups along the Sichuan frontiers; Wu moved into modern Vietnam; and Wei steadily gained influence over Korea and southern Manchuria. Yet the real conflict remained in China, since Wei, which controlled the area historically known as the Middle Kingdom and had access to its resources, had a decided advantage. By 263, it had defeated and expanded into Shu Han, and in 280 the Western Jin (265–316), its successor, once again brought China under one rule by subjugating Wu, thus ending the Three Kingdoms period. Unity, however, proved to be elusive. Within Wei itself, internal rivalries and turmoil undermined efforts at consolidation. Internecine struggles among military commanders plagued Wei, as the Cao family lost control. Finally, in 265, Sima Yan (236–290), one of the military leaders, defeated the other generals, overthrew Wei, and established himself as Emperor Wu of a new Western Jin dynasty.

The Western Jin’s victory in 280 hardly created the stability needed for a strong dynasty. Sima Yan could not galvanize support from the great aristocratic families, who did not wish to knuckle under to a powerful central government. The tensions between centralization and the authority of local families had not subsided and would not abate for the rest of Chinese history. Such internal struggles weakened China and compelled it to make concessions that prevented it from exercising the power required to govern. Sima Yan tried to bring the elite families under his control and to reduce their independent authority. He sought to place the peasantry and the estate owners on the tax rolls but was unable to enforce his will on the elite families. The large estates often evaded taxes, and the aristocratic families frequently prevented census takers from including the peasants who worked estate lands on the tax rolls. Without such revenue, Sima Yan could not perform the tasks expected of an emperor, and the dynasty increasingly lost support. His death in 290 ended whatever stability had existed. Within a short time, the steppe nomads north of China attempted to fill the vacuum caused by the lack of an effective government.

ISE OF

S

OUTH

C

HINA

Non-Chinese peoples, recognizing the disarray in China, capitalized to form Chinese-style dynasties in north China, causing many Chinese to flee to the south. Fearing the threat posed to their culture by so-called northern barbarians, they migrated to a region where they could retain control. The less organized non-Chinese and Chinese of the south were no match for the immigrants, who took charge and whose efforts led to the growing assimilation of the native populations. The south was gradually integrated into Chinese civilization. Over at least three centuries if not longer, the Chinese spread throughout the south, which offered the bonus of more-fertile territory. In time, the Chinese in the south began to perceive of themselves as the standard bearers of Chinese culture and started to portray their compatriots in the north as less suited to inherit the mantle of Confucian civilization because they had fallen under foreign domination, had been influenced by foreign customs and institutions, and had strayed from Confucian orthodoxy. As a result, the south and the north were divided, and each section had separate dynasties – a development that lent its name to the era, the

Nanbeichao

(Period of Southern and Northern Dynasties, 220–581).

Yet, despite their brave invocations of traditional Chinese history and culture, the Chinese of the south could not unify the country. Six dynasties chose capitals at Nanjing (then known as Jiankang), but none could galvanize sufficient support within their own regions to overwhelm the north. In 31 7, the first of these dynasties selected Jin, the same dynastic name that Sima Yan had chosen several decades earlier. Scholars refer to the dynasty as the Eastern Jin (317–420) to distinguish it from its predecessor, which had been based in the north. None of the six dynasties could control the aristocratic landowning elite that often dominated the military. Struggles among commanders were common, and the ensuing wars and revolts led to the decline and fall of some previously prominent families, which resulted in increased social mobility as new families came to the fore. Thus, the great families of the Han faced challenges from newly powerful families who had made better adjustments to the new environment they encountered in the south. When one dynasty finally restored unity in the sixth century, great aristocratic families would still play significant political roles, but their composition would differ somewhat from that of the families of the Han. This so-called oligarchy did not remain monolithic, as the fortunes of individual families varied considerably.

Each succeeding southern dynasty was wracked with the same frustrating impediments. All wanted to reoccupy the traditional northern heartland of China. Although the Eastern Jin succeeded in conquering the southwest, including Sichuan, it could never consistently challenge and gain additional territory from the northern foreign dynasties. In 420, its failures and internal weaknesses permitted Liu Yu (363–422), one of the dynasty’s leading commanders, to overthrow its last ruler and to establish his own short-lived dynasty, the Song (often referred to as the Liu Song, 420–479, to distinguish it from the later and more renowned Song dynasty), and to assume the title of Emperor Wu. Although the new ruling group was initially promising because of Liu Yu’s own abilities, it barely lasted for two generations before falling to rival leaders, who established the Southern Qi (479–502) dynasty. Yet again the Southern Qi could not suppress internal dissidents, and indeed divisions arose in the ruling family, culminating when one family member overthrew the last emperor and founded the Liang (50 2–579) dynasty.

Emperor Wu, the Liang founder, differed from most other rulers of this era in the longevity of his reign. His almost five decades on the throne witnessed a period of domestic peace, offering opportunities to strengthen the state and to emerge as a potential unifier of China. Wu also had the advantage of state sponsorship of Buddhism, which ensured the support of its monks. An ardent convert to Buddhism, he issued regulations banning the use of animals or parts of them for sacrifices or medicines. He also built temples, encouraged wealthy and pious patrons to donate funds to the monasteries, and lectured and wrote explanations and interpretations of Buddhist texts. His attempts to limit the practice of Daoism and the activities of Daoists were the first indications of tensions between the two religions. However, Wu’s devotion to Buddhism and particularly his attacks on Daoism alienated many in his domains and undermined efforts at unity. In addition, some Confucian scholars deplored the gains made by the Buddhists and criticized them and their ideas as “barbarian.” Wu’s patronage, nonetheless, bore fruit, as later sources reveal that the total number of monks increased from 32,500 to 82,700 during his reign.

Yet hostility based on his favoritism toward Buddhism and, even more important, his inability to control his own commanders and the elite led to the same disunity that prevailed among the earlier dynasties. The ensuing weakness permitted a non-Chinese commander from the north to seize most of the dynasty’s lands and to briefly occupy the Liang capital. After this loss, the Liang made a feeble attempt at restoration in its southern domains, with a different city as the capital, but its vulnerability had been revealed. Within a decade, Chen Baxian (503–559), still another military commander, led a successful coup d’état and founded the Chen (557–589), the last of these southern dynasties. The Chen controlled less territory and was thus weaker than the Liang, which reduced its chances of survival. Like its predecessors, the Chen was plagued by internal rifts and weak government, which rendered it vulnerable when the Sui, a northern dynasty, challenged it in the 580s.

The southern Chinese dynasties could not resolve the problems that the northern immigrants had brought with them to the south. Leading families, who supplied the most important military commanders, continued to challenge and thus enfeeble the central government. Large landowners evaded taxes and had their own military forces, which undermined the dynasties’ efforts to dominate their domains. Conversion to a new religion such as Buddhism, which often served to unify people in a state or region, did not translate into an effective and cohesive government. Turbulence in the form of coup d’états and struggles for succession confronted each dynasty. Assertions of China’s indigenous traditions and affirmations of Buddhism were insufficient for restoration of the Chinese empire.

OREIGNERS AND

N

ORTH

C

HINA

North China was the region influenced by non-Chinese peoples during this era. The turbulence of the Three Kingdoms period left China vulnerable, permitting foreigners living north of China to make incursions on or conquests of Chinese soil. China was no doubt influenced by these foreigners, who established dynasties to govern north China. They introduced powerful military forces and martial values into the north. One of the foreign dynasties fostered Buddhism and played a vital role in its transmission. None of the dynasties initiated an attack on Confucianism or on Chinese tradition. Indeed they frequently portrayed themselves as accommodating to Chinese culture in order to gain the allegiance of the subjugated Chinese population. Nonetheless, with ever-greater influence from the so-called barbarians, the north became, to the Chinese who migrated to the south, less and less regarded as Chinese. Yet a strong core of Chinese traditions and institutions survived in the north.

For almost a century after the fall of the Han, Chinese dynasties managed to rule much of the north. The Wei and then after 265 the Western Jin ruled much of the north, but their internal squabbles undermined them and disrupted relations with the northern frontier peoples. Trade with China, which was a vital source of income for the northern steppe peoples, gradually diminished, prompting frustration and then foreigners’ efforts to obtain, by force, products denied them by chaotic conditions within China. In these difficult times, the perpetual agreement whereby a descendant of the Xiongnu leaders (or

shanyu

s) was a hostage at the Chinese court ended. With China fragmenting, the successors of the original Xiongnu groups had little to gain from such cooperation or submissiveness to the Chinese court. In 304, the

shanyu

hostage fled from the Western Jin capital and declared his independence. Having been exposed to Chinese culture, he adopted a Chinese name for his dynasty. Han, or Later Han, the name he initially selected, naturally resonated in China and revealed an effort to win over the Chinese by appearing to have become sinicized. The Later Han dynasty (later renamed the Zhao) moved so briskly to capitalize on China’s internal conflicts that it occupied Luoyang in 311 and Changan in 316, in the process imprisoning two emperors of the tottering Western Jin dynasty.

Having gained control of much of the north, the Later Han/Zhao rulers sought to win the allegiance of the people by establishing a Chinese-style dynasty. However, this attempt created fissures among the conquerors. Many wished to retain their traditional nomadic society, with occasional forays into China to expropriate its resources, and opposed the creation of a Chinese-like sedentary society. Unlike the founders of the Later Han/Zhao, they sought to avert Chinese influence for fear of “spiritual pollution” of their traditional way of life. Also unlike their more sinicized brothers, they did not wish to recruit and cooperate with the Chinese to set up an administration capable of ruling the vast Chinese empire. Raids and conquests, not governance, were their goals. Attacks, pillaging, and retreat into the northern steppe lands had customarily been their tactics, and they did not relish abandoning their freer and more mobile existence. These attitudes clashed with those of the Later Han/Zhao rulers, who employed Chinese bureaucrats to assist them in ruling China. The growing accommodation to Chinese culture of the Later Han/Zhao elite provoked hostility among the nomads, which rapidly resulted in a violent rift and the undermining of the dynasty’s attempts to establish a stable rule over China.