A History of China (22 page)

Read A History of China Online

Authors: Morris Rossabi

This orderly conception of the universe also proved to be a potent political symbol. Successive founders of dynasties selected an element and the associated color to represent the new rulers. The choice was largely determined by their predecessors’ symbols, which appeared in a continuum of fire, water, earth, wood, and metal, with each transcending and overwhelming its predecessor. Han rulers chose at least two distinct representations, the earth with the matching color of yellow and fire with its attendant color of red. They also abided by the other elements – taste, animals, etc. – in the rituals and ceremonies carried out at court. The linking of

yin-yang

and the Five Phases, which apparently enjoyed widespread popular support during the dynasty, no doubt bolstered Han rule.

However, Confucianism provided the repository for the major ideas, beliefs, and rituals of the dynasty. The Han became associated with Confucianism. Dong Zhongshu probably had as much as anyone to do with the emergence of Confucianism, for his views influenced Emperor Wu, who became a patron, initiated Confucian rituals at court, established the Imperial Academy (Taixue) where potential officials could be trained, and promoted scholarship, including the selection of the Five Classics as the main orthodox texts. Commentaries were written to provide official interpretations of these somewhat cryptic texts. For example, the Guliang and Gongyang commentaries attempted to supply greater moral significance to the dry accounts preserved in the

Spring and Autumn Annals

. The appointment of Confucian tutors to the emperors early in the Former Han solidified links between Confucian scholars and the government. The court appeared to value education, and, although scholars did not dominate government, learning slowly became a criterion in the selection of officials. With growing acceptance at court, Confucianism and its attendant practices of ancestor worship and filial piety took hold among the populace.

Confucianism also sought to define the role of women during this time. Ban Zhao, an extraordinarily accomplished woman who completed the first dynastic history of China, wrote

Lessons for Women

(

Nüjie

), on proper behavior. She counseled women to be submissive to their husbands and to respect their male relatives, including brothers, fathers-in-law, and brothers-in-law. She also advised women to remain faithful and to allow their husbands to bring concubines into their households. On the other hand, her text states that women ought to become well educated, mostly in order to assist their husbands. Ban Zhao herself was prodigiously talented. In addition to editing the final version of the Former Han dynastic history and writing the

Lessons for Women

, she composed poems and expressed considerable interest in mathematics and astronomy. Yet obedience to males was her principal message for women. From this time on, educated women throughout traditional Chinese history read and memorized the text, and even women who could not read or write were taught to memorize the work.

Although Ban Zhao’s prescriptions for women may have been well known, it is unclear whether they reflected reality. Were gender roles and statuses as clear cut as Ban Zhao specified them? In practice, did women have more rights than Ban Zhao’s text has us believe? In a few of the later dynasties, women could own property, and some in the upper classes took an active role in society. Were they submissive within the family or did they have leverage, especially after giving birth to a male heir? Similarly, kinship relations, as described in Confucian texts, may not have always fit the stereotypes of filial piety and of younger generations owing respect, if not obeisance, to the older generation. Even at court, there were examples of sons not on good terms with and, on occasion, challenging their fathers. Such unfilial behavior was replicated among ordinary folk in other dynasties. Evidence about women and kinship relations in the Han is limited. Gender and family relations in later dynasties, for which more information is available, will be covered later in the book.

The shocking events at the Later Han court and the accompanying turbulence in society at large were disturbing. Like other court institutions, the Imperial Academy lost its vigor, and its scholars and students became less attentive and increasingly corrupt. Confucian scholars who advocated reform scarcely had much influence. In these trying times, some Confucians sought remedies by proposing harsher laws and better means of recruiting moral officials. Invocations to abide by Confucian morality and veiled warnings about the loss of the Mandate of Heaven did not forestall the decay, corruption, and disarray at court. Disputes among the Confucian scholars about their doctrines and about Confucius himself also undercut the status of Confucianism. The fall of the Later Han therefore dealt a damaging blow to the philosophy that provided its ideological underpinning.

AN

L

ITERATURE AND

A

RT

Han literature is often closely identified with the works of the historians Sima Qian and Ban Gu. According to tradition, Sima Qian’s

Shiji

(or

Records of the Grand Historian

) owes its origins, in part, to filial piety. Sima Tan (ca. 165–110

BCE

), Sima Qian’s father and the grand historian and astrologer during Emperor Wu’s reign, had conceived a plan to record events of the past and to write accounts of the great historical figures. He collected source materials but died before actually beginning to produce this historical record. Traditional sources portray a touching deathbed scene in which the grand historian elicited a pledge from his son, his successor in the post at court, to finish the grandiose project he had embarked upon. Sima Qian (145 or 135–86

BCE

) fulfilled his promise, despite numerous obstacles and personal losses. One such setback resulted from his support for Li Ling (d. 74

BCE

), a general who had been defeated and then captured by the Xiongnu. In defending Li Ling and arguing that his troops had been ill-supplied and had been hastily dispatched to meet the enemy, Sima Qian alienated the emperor, who in his anger had the grand historian castrated. Customarily, people so punished committed suicide. Instead Sima Qian persisted in his work, believing that the future would absolve him for not bowing to the customary dictates of his time. He had a filial obligation to complete the history, but he also believed that his work would clear his reputation from the aspersions cast upon it because he had not followed societal norms.

His work, particularly its organization, would provide a model for future histories. He divided his book into four sections, a pattern that would be followed by the twenty-five subsequent official dynastic histories. The first section, known as the “Basic Annals,” consisted of a year-by-year account of dynasties and rulers of the past, focusing primarily on events at court. The second section was composed of chronological tables citing the significant dates and events in the country’s various regions and “feudal” states, while the third part contained treatises or essays concerning taxation, the calendar, rituals, the military, and religions. The last section provided biographies of leading officials, princes, consorts, philosophers, merchants, assassins, and poets and descriptions of foreign lands and states.

Sima Qian was the first Chinese historian to devote much of his work to accounts of the merits and defects of individuals. History, in his hands, became the study of great men, their attributes, and their actions. The biographical format served as a splendid vehicle for the didacticism implicit in the work, and the actions of both the virtuous and the treacherous offered models of proper and improper behavior. The emphasis on anecdotes in the biographies conveyed the values that Sima Qian and his society perceived as the most conducive to the development of good moral individuals and a harmonious society. He focused on the eminent, but, unlike earlier Chinese histories, did not ignore commoners or individuals with nonelite occupations. Such a widening of the scope of biographies was useful, for ordinary people could more readily identify with this work than with an account that dealt exclusively with the upper classes. Sima Qian often added a personal touch to the biographies, making his own value judgments and criticizing the actions of some of his subjects while praising others. He did not pretend to be totally objective.

The “Basic Annals” and the accounts of the Zhou and early Han were relatively straightforward, but Sima Qian occasionally appended his own comments. Despite his critical and didactic analyses, much of the work, particularly about the distant past, consists of paraphrases and summaries and, in some cases, verbatim copies from earlier texts. As the history approached his own times, however, his own original writing surfaced. In these sections, he no longer simply followed the accounts and interpretations of other texts but offered original conceptions of events closer to his times. Much of the section on the Han was new, reflecting Sima Qian’s own views. In these sections, his didacticism surfaced. He presented these accounts so that readers would be exposed to proper role models. This didactic emphasis in the

Shiji

would have a remarkable impact on future historical writing. The dynastic histories would use the same or similar organizational schemes as the

Shiji

, as well as using history for didactic purposes.

While the next major history shared the

Shiji

’s didactic motivations and organization, it diverged somewhat and became the closest model for later dynastic histories. Like the

Shiji

, it originated with the father of those historians who received credit for it. Ban Biao (3–54), who lived through and witnessed the career of Wang Mang, had decided to continue the

Shiji

through the Former Han dynasty. He died before he got very far, but his son Ban Gu, like Sima Tan’s son Sima Qian, assumed the task that his father had just begun. Yet Ban Gu charted a different course, for he was determined to produce a work that could stand on its own. He elected to write an independent study of the Former Han, ending with Wang Mang’s usurpation. The work he compiled was the

Han shu

(or

History of the [Former] Han

), the first of the dynastic histories. He too did not live to complete the work, dying in prison while awaiting the results of an investigation into totally trumped-up charges against him. The court recruited his remarkable sister, Ban Zhao, to finish the history, but Ban Gu has traditionally been credited as the compiler.

The

Han shu

borrowed from the

Shiji

, but eventually included new material concerning the period after Sima Qian’s death. Unlike the

Shiji

, it confined itself to a single dynasty, and its relative closeness to the events described made it less prone to accepting legendary and dubious accounts. Ban Gu was generally more reliable than Sima Qian but could, on occasion, be as credulous. Yet his work is more precise than the

Shiji

, and, unlike Sima Qian, he rarely intruded his personal judgments. He adopted a more formal and more balanced tone and excluded the revealing asides that Sima Qian incorporated in his work. Ban Gu’s more impersonal style served as a more fitting model because the later dynastic histories, which were produced under court sponsorship, were collaborative efforts and precluded personal touches. Despite its significance as a model, the

Han shu

has been overshadowed by Sima Qian’s work, with its more idiosyncratic and colorful style and anecdotes.

It should come as no surprise that the first political unification of China engendered valuable developments in both poetry and prose. The court itself contributed to such developments. Emperor Wu founded a Music Bureau in 120

BCE

to devise music and verse for official ceremonies. He and later emperors commissioned Bureau officials to compose songs for court occasions. These commissions led to the creation of new poetic forms to evoke some of the traditional themes of Chinese poetry – sorrow at separation, love, and capture by the enemy in warfare. The

fu

(or prose poem), which supplemented the telegraphic and concise language and images of other kinds of poetry with descriptions beyond the constraints of the poetic lines of the times, became an important form and occasionally received court patronage. Descriptions in some

fu

of the capital cities and palaces and of court entertainments yield evidence of Han splendor. The greater length and expansiveness of the

fu

coincidentally dovetailed with the Han expansionist foreign policy, particularly during Emperor Wu’s reign.

Figure 3.3

Belt buckle, Han dynasty (206

BCE

–220

CE

), China, third–second century

BCE

, gilt bronze, H. 2¼″ (5.7 cm), W. 1½″ (3.8 cm). New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1918. Acc.no. 18.33.1. © 2013. Image copyright The Metropolitan Museum of Art / Art Resource / Scala, Florence

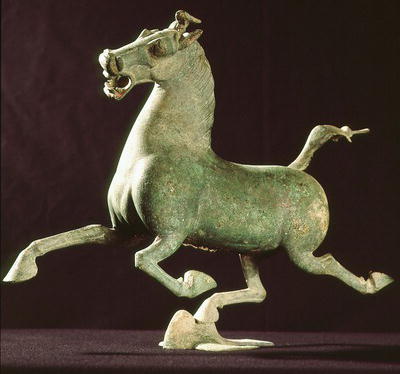

Figure 3.4

Flying or galloping horse, western or “celestial” breed, standing on a swallow, bronze, Eastern Han dynasty, second century

CE

, from Wuwei, Gansu province, China, 34.5 cm. © The Art Archive / Alamy