A History of China (58 page)

Read A History of China Online

Authors: Morris Rossabi

H

ISTORIANS

of China have generally portrayed the Qing as a typical Chinese dynasty and the Manchu rulers as gradually adopting the style and trappings of traditional Chinese emperors. The Manchu origins of the Qing are thus slighted and possible deviations from the norms of Chinese dynasties have hardly been explored. Although the Qing restored and used many Ming institutions, its rulers and officials, on occasion, initiated new policies that diverged from Chinese practices and views. However, traditional Chinese historians have asserted that the various ethnic groups, including the Manchu conquerors, in the Qing accommodated to Chinese civilization and eventually became sinicized. They applied the same paradigm to the foreigners who temporarily annexed or actually conquered part or all of China. A number of specialists, who espoused the so-called New Qing History, challenged this view, arguing that the Qing developed a multiethnic empire. They note that the early Qing emperors perceived themselves to be Manchus and different from the Chinese, that they favored and patronized Tibetan Buddhism, and that they initially incorporated aspects of Mongolian culture, including the use of the Mongolian script for the Manchu written language. In addition, they embarked upon territorial annexation and created the significantly larger China of modern times, a policy of expansionism that ran counter to the dictates issued by most emperors and officials in the Chinese tradition. Both viewpoints are useful in understanding different aspects of the Qing dynasty.

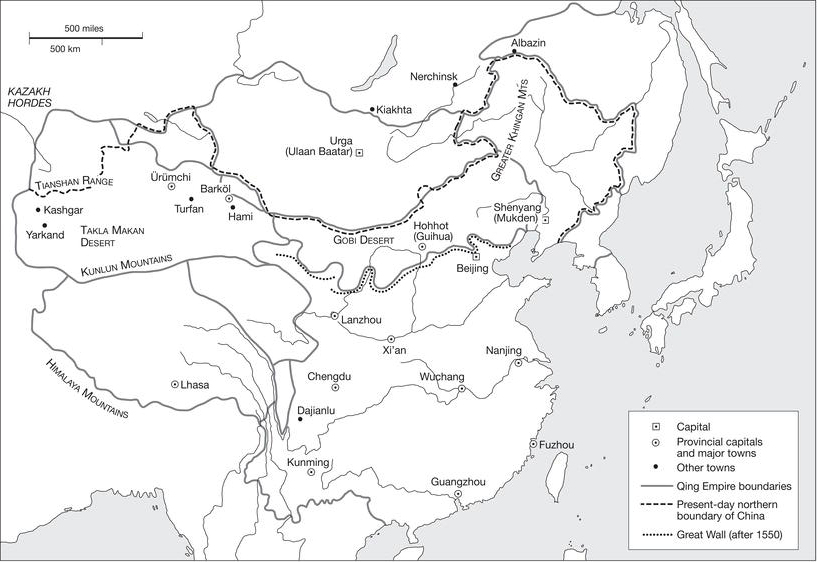

Map 9.1

Qing dynasty, ca. 1760

Before the conquest of China, the Banners had become the principal means of organization and included not only Manchus but also Chinese, Mongols, and Koreans. Indeed, the Manchus’ successes may have been due, in part, to their ability to recruit foreigners who offered skills that they lacked. By incorporating skilled foreigners into their administration, they not only strengthened their ability to rule but also helped to turn the dynasty into an empire.

Hong Taiji, ambitious and politically astute, succeeded his father Nurhaci and laid the foundations for the establishment of the new dynasty. After he consolidated his position, he turned against one of the more vulnerable foreign groups adjacent to the Ming border, the Chahar Mongols of modern Inner Mongolia. Despite his direct connection to the Chinggisid line, the Chahar ruler, Lighdan Khan, though a supporter of Buddhism and a patron of a number of literary compilations, had alienated many Mongols, who betrayed him and joined Hong Taiji. By 1634, Lighdan Khan’s lands in Inner Mongolia had fallen to the Manchus. Shortly thereafter, Hong Taiji constructed a capital city in Mukden and began to establish a bureaucracy composed originally of Chinese officials. With the assistance of these foreigners, he organized a government and, as noted earlier, in 1636 he proclaimed himself the emperor of the newly minted Qing dynasty.

Hong Taiji died in 1643, leaving behind a five-year-old son who would assume the title of emperor. Hong Taiji’s brother Dorgon became regent for his nephew. For the next seven years, until his premature death, Dorgon determined policies for the dynasty. He actually crossed into China and devised the strategy for the defeat of Li Zicheng, the rebel who had captured Beijing and overthrown the Ming. He set the stage for Sino–Manchu rule over China by recruiting Chinese advisers to establish a government. He imposed some control over the Manchu princes and leaders of Banners and placed himself in charge of two Banners. His extraordinary power as regent to the young emperor generated considerable hostility among influential princes, and his sudden death permitted his enemies to imprison or execute his allies and to vilify him. They accused him of seeking to usurp power, of humiliating effective officials, and of living in a grand style in newly constructed palaces. These kinds of splits among the Manchus subsided in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, when the Qing was at its height, but revived again in the nineteenth century and contributed to the erosion of the dynasty’s power.

Almost four decades elapsed before the Qing finally overcame resistance from Ming-dynasty loyalists. Once Qing forces had defeated Li Zicheng, they moved quickly to occupy most of north China. Parts of south China remained havens for Ming loyalists. A descendant of the Ming proclaimed himself to be emperor in Nanjing, but Qing armies overwhelmed him. Another descendant, based in Fuzhou, challenged the Qing, but in 1646 Manchu troops crushed his forces and executed him. Zheng Chenggong and his descendants maintained their control over Taiwan until 1683, when the Qing pacified the island. Wu Sangui (1612–1678), a commander who had earlier cooperated with the Manchus, challenged Qing authority in Yunnan and Guizhou, again in south China. A prolonged conflict, known as the War of the Three Feudatories, lasted from 1673 to 1681, when Qing armies overcame Wu’s forces.

The Qing had defeated these opponents by the early 1680s, at which point it emerged as one of the world’s great empires. The Moghul Empire in India and the Ottoman Empire in the Middle East were at their height, but no other country in Asia was as populous or had as powerful an army as the Qing. Its agricultural economy produced sufficient food for a growing population as well as such cash crops as tea, tobacco, and sugar. Domestic commerce increased, leading to the development of new vibrant cities, especially on the southeast coast. The cities also housed factories and workshops producing silk, clothing, porcelain, and printed books. Western merchants reached China seeking silk, tea, and porcelain and were willing to pay in silver for these goods. Jesuit missionaries, originally dispatched to convert the Chinese to Christianity, were so dazzled by China’s glorious civilization that they did not abide by papal instructions to condemn Confucian rituals and to depict Confucius as a heretic.

When the Manchus took power, they faced the same governance dilemmas the Mongols had confronted four centuries earlier. How could they, as a tiny group, rule the vast Chinese population? Moreover, as an expansionist dynasty, which eventually conquered and occupied large domains in Mongolia, Tibet, and what came to be known as Xinjiang, how could the Qing dynasty govern a variety of non-Chinese peoples? As important, how could the Manchus retain their identities in a basically Chinese domain in which they were colossally outnumbered? The closing of Manchuria to Chinese colonization, support for the Manchu language and shamanism, and maintenance of cultural distinctions such as avoiding the adoption of the Chinese practice of bound feet for women all helped.

Yet the Manchu bannermen were in a precarious position. They received land grants and stipends from the state, but officers frequently commandeered the land and the stipends became increasingly insufficient. Many had to borrow funds to survive. Most were illiterate because the court had not provided them with an education in Manchuria. Without this skill, they could not serve in the bureaucracy. Several Qing emperors, especially Kangxi (r. 1662–1722), sought to foster literacy but found that many bannermen had turned to spoken but not written Chinese and had scant knowledge of the Manchu language. The court thus had to rely on Chinese to staff much of the bureaucracy. The civil-service examinations used the Chinese language, favoring the Chinese.

RESERVING

M

ANCHU

I

DENTITY

Dorgon and Emperor Kangxi, who eventually acceded to the throne in 1662, had devised policies to set up and preserve Manchu rule, especially among the military. The basic quandary they faced was to preserve their identity in an almost totally Chinese environment, in which they were outnumbered by about a hundred to one. Their strategy first entailed continued use of the Manchu language. Government documents were to be written in Manchu as well as in Chinese, and the Manchu elite continued to be taught the language. A second part of the strategy was affirmation of traditional Manchu customs and rejection of certain Chinese customs. The Manchu men distinguished themselves by compelling Chinese men to wear the queue hairstyle. A third element of their strategy was to maintain Manchuria as their homeland and to prevent Chinese colonization in their traditional domain. Manchu culture and civilization would presumably flourish and avert tainting by Chinese customs. The Manchus in Manchuria would remain unpolluted by Chinese practices and beliefs and the region would provide an escape hatch should the Chinese overthrow and expel the Qing rulers.

Yet, ironically, the Manchus needed Chinese collaborators. Without them, they could neither have defeated the Ming nor have established their new dynasty. With Chinese support, they adopted the traditional Chinese system of six ministries, the Censorate, and a local administration based upon division of the country into provinces. Loyal Chinese staffed many of these offices under the watchful eyes of Manchus. Similarly, the Qing restored the civil-service examinations as the principal means of selecting officials. With such Chinese assistance, the Manchus achieved stability in north China within the reign of the first Qing emperor.

ANGXI AND THE

H

EIGHT OF THE

Q

ING

Kangxi was disappointed over the paucity of Manchu bannermen who could become scholar-officials, but otherwise he presided over a generally prosperous and expansionist China. His father succumbed to smallpox, compelling him to take the throne at the age of nine, in 1662. Five years later, chafing under the restrictions on his power imposed by Regent Oboi, he asserted his authority, had Oboi arrested, and executed several of the regent’s allies. His own writings, which have been translated in the form of a diary, show him to be a man of great intellect and sublime sensitivity who understood the value of learning, as well as of military training.

Unlike many emperors in Chinese history, Kangxi paid considerable attention to governance. He sought to stabilize Manchu rule in China, in part by ingratiating himself with the Chinese literati. Like a typical Chinese emperor, he supported Neo-Confucian philosophy and such scholarly enterprises as work on dictionaries of the Chinese language (for example, the

Kangxi zidian

), the Ming dynastic history, and a major encyclopedia. He recruited Chinese so-called bondservants to perform a variety of tasks, including acting like the Ming-dynasty censors in surreptitiously reporting about the performance of provincial and local officials. These censors also handled the imperial court’s personal affairs. Probably most important was Kangxi’s own diligence and involvement in government. He devised a system of secret memorials by which officials could contact him. He was serious about undertaking tours of inspection throughout the empire to gauge for himself conditions in his far-flung domains. He cultivated the Chinese literati and was an avid student of both Chinese and foreign (especially Western) knowledge, and he reduced the monetary and labor demands on his Chinese subjects. At the same time, he was determined to affirm his Manchu identity by maintaining Manchu customs at court and by participating in martial activities such as hunting. In sum, he and the other early Qing-dynasty rulers attempted to achieve a proper balance in their roles as emperors of China and leaders of the Manchus.

ESTERN

A

RRIVAL

Having proven his mettle in domestic affairs, Kangxi also confronted foreign-policy issues that earlier emperors of China had not faced. Instead of dealing with the primarily pastoral peoples north and west of China, whom the Chinese often considered to be barbaric and less sophisticated, and the agricultural but less populous states south of China, Kangxi had to devise policies for dealing with the representatives of the Western civilizations. To be sure, earlier Chinese dynasties had had relations with Indian, Iranian, and Arabic empires, not to mention the various rulers of central Asia, and had been influenced by their religions, cultures, and technological accomplishments. However, such relations had often been on China’s terms, and these civilizations were far enough away and had not made sufficiently great leaps forward in weaponry that they could challenge and perhaps threaten China. The newer arrivals from the West, who reached China overland and by sea, proved to be more troublesome.

Within a few decades of Vasco da Gama’s discovery of the sea route around the Cape of Good Hope from Europe to China, Portuguese merchants began to land on China’s eastern coast. Having learned about the spices from the East and seeking to extract profits from this lucrative trade, Portuguese sailors and pirates were determined to establish bases or colonies in Asia from which to dominate the commerce. Because their men-o’-war were superior to the Asian ships and navies, in 1510 they occupied Goa (an island adjacent to the Indian coast) and Malacca (in present-day Malaysia), which was directly across the island of Sumatra and commanded the straits that led to southeast China. Their powerful naval forces permitted them to play a vital role in Asian trade and to be labeled the Pepper Empire. By the early sixteenth century, they were serving as intermediaries in the commerce among the east Asian countries while also transporting spices and earning considerable profits. Initially they did not make a good impression because they avoided court regulations on commerce and also traded for Chinese children, whom they sold as slaves. After numerous unpleasant incidents, including the imprisonment of an official Portuguese ambassador, the two countries came to an agreement in 1557, with the Portuguese securing a base in Macao, an island off the southeast coast of China, which the Chinese continued to govern. However, in 1887, when China was at its nadir, Portugal established its own rule over Macao that lasted until 1997, the year China reasserted its claim to the island.