A History of China (53 page)

Read A History of China Online

Authors: Morris Rossabi

Wang had underestimated the power of the Mongol leader, and the expedition proved to be disastrous. With scant intelligence concerning the enemy, Ming troops crossed into the lands of the steppe pastoralists. Vulnerable from the very outset due to poor planning and logistics, they were surrounded. Wang was killed and the emperor was captured in a battle near Tumu, the site of a postal station. However, Esen did not capitalize on his victory. He waited for a month before marching on Beijing, affording the Chinese time to construct additional fortifications and to enthrone the emperor’s younger brother as the new ruler. By the time Esen’s troops reached the capital, Beijing could readily withstand a lengthy siege. Faced with such resistance, Esen abandoned his siege and returned to the steppe lands. A year later, he repatriated the emperor, and in 1454 he was murdered in one of the many struggles for leadership in Mongol history. The threat posed by the Mongols receded, but the debacle at Tumu had revealed weaknesses and poor judgment at court.

ONSPICUOUS

C

ONSUMPTION

Nonetheless, the rapid acceleration in the commercialization of agriculture and the development of urban centers encouraged some landlords to move to the cities. Such absentee landlords settled in towns both to have greater access to luxury products and as protection from peasant dissatisfaction and uprisings. Their profits as well as those of wealthy merchants were not always used for capital accumulation that would be invested in advances in technology or other means of increasing production. Instead they expended vast sums on luxurious lifestyles. Wealthy merchants also sought luxury goods and evaded sumptuary laws that the government could not enforce. The state could not control the lively market economy and limit extravagance. Merchant handbooks, which publicized specific luxury goods from various areas of China as well as exotic products from abroad, began to be published, although the status of merchants themselves was not elevated. What art historian Craig Clunas has labeled “superfluous things” assumed greater significance for the elite’s social status and aesthetic appeal. The choices the official class and merchants made – for example, about clothing, furniture, gifts, food, types of tea, and interior decoration – played a vital role in defining them. This pattern of consumption was especially prominent among the nouveau riche in the lower Yangzi valley of south China.

Such conspicuous consumption did lead to cultural efflorescence. Art collection became important as a means of “taste,” which, in turn, related to social stratification. Connoisseurship about bronzes, rocks, jades, inkstones, calligraphy, lacquer, ceramics, seals, and furniture helped to confirm elite status, and these decorative arts, as judged by prices in the market economy, were, perhaps for the first time in Chinese history, valued as highly as painting, formerly the province of the elite. Painters also produced for the market and not merely for the use of the traditional official class and for their edification and pleasure. Painting became just as much a luxury product as the decorative arts, and owners became more concerned about a painting’s authenticity and possible forgery and fraud, as well as proper care and preservation of paintings, including limitations on exhibiting these fragile artworks.

The emphasis on material culture altered perceptions of the decorative arts. Craftsmen gained in stature, and potential owners strove to discover the names and the geographical origins of artisans before purchasing an object. At the same time, officials and merchants became interested in collecting jades, bronzes, and calligraphy of the past. They also sought foreign luxury products, and merchants were in a position to obtain these goods even if it required them to engage in smuggling.

Although the economy became increasingly monetized, and China was gradually becoming part of the world economy, the segment of the population affected by these trends was relatively small. Most peasants produced for themselves and for local markets. The larger estates that produced specialty crops designed for export were the main institutions and groups influenced by regional or global developments and were, on occasion, consumers for the Chinese and world material culture.

Growing urbanization, the greater economic opportunities afforded by regional and global developments, and the somewhat freer environment allowed a few women to break away from the traditional stereotypes, although countryside women did not benefit. Women with more independent status became merchants, entertainers, midwives, artists, or shamans. The growth of the textile industry, mostly a female enterprise, provided additional opportunities. However, women’s property rights had eroded since the Song dynasty. Households without sons now had to find nephew successors to land and property. At the same time, widows could no longer inherit land and also faced considerable pressure, due in large part to Neo-Confucianism, to remain chaste after a husband’s death.

RTS IN THE

M

ING

Ming cultural developments reflected the urbanization and interest in material culture and yet the aversion to foreign influence that characterized court policy. Like its prospective officials – who, in the so-called “eight-legged essay” to pass the civil-service examinations, needed to master the rigid form, with a specified number of sentences, considerable parallelism, and numerous allusions to classical texts – many thinkers, artists, craftsmen, and writers often, but not always, worked within traditional modes. Yet important innovations were introduced in philosophy, literature, and the arts. Creative individuals produced works within existing forms but also experimented and developed new types of expression.

Although Ming porcelains reflected many of the shapes and designs of the past, an attempt to cater to foreign markets also influenced the decorations and types of ceramics produced. Jingdezhen, the major porcelain center in the province of Jiangxi, and Dehua, another center in Fujian province, had produced ceramics during the Song and Yuan periods. In Ming times, Jingdezhen became renowned for its blue-and-white porcelains and Dehua for its white wares. The fine clay nearby as well as a reservoir of skilled potters enabled Jingdezhen to produce flasks, bowls, jars, brush rests, and lamps, which were often decorated with flowers, grapes, waves, and other motifs, some of which had been used earlier in paintings and textiles. The cobalt blue used in decorations came from central Asia, an indication of the impact of the world beyond China. In addition, some of the wares had Persian or Arabic (or, less frequently, Tibetan) inscriptions, an indication that they were produced either for Muslims and other foreigners in China or, more likely, for foreign trade. The sizable collections of blue-and-whites and indeed other porcelains at the Topkapi Museum in Istanbul, the Ardebil Shrine in Iran, and various Southeast Asian states attest to the scale and range of the market for Chinese porcelains. By the late sixteenth century, market demand had fostered mass production and a resultant decline in quality. As relations with central Asia became more turbulent, Ming potters could not readily obtain what the Chinese referred to as “Muslim blue” or fine cobalt, which further undermined quality. Yet both the domestic and foreign demand for Chinese porcelains continued to grow. The foreign market increased with the arrival of Europeans in China and, within a short time, Ming potters began to produce wares suited to European tastes. These wares would influence Turkish, Iranian, Southeast Asian, and Japanese ceramics, as potters would borrow designs, shapes, and colors from Chinese craftsmen.

Figure 8.2

Jar, porcelain painted in underglaze blue, H. 19” (48.3 cm), Diam. 19” (48.3 cm). New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Robert E. Tod, 1937. Inv. 37.191.1. © 2013. Image copyright The Metropolitan Museum of Art / Art Resource / Scala, Florence

As in earlier dynasties, textiles continued to be of great consequence in the economy for the roles they played in foreign relations, social and political status, and domestic and foreign trade. Mass production of silk in large workshops and small factories in Suzhou and other nearby centers near the Yangzi River began to characterize the silk industry, as did porcelain production in the late sixteenth century. Tremendous foreign and domestic demand led to the rapid growth of the industry. The increased amount of silk meant that it could be used ever more frequently and in even larger quantities in foreign relations. Like the dynasties from the Han on, the court offered bolts of silk, as well as silk robes, to nearly all the tribute missions that reached China. The court granted even the valuable dragon robes to foreign emissaries. These long robes were generally reserved for officials and for the emperors and princes, but envoys or rulers from foreign lands with strong bonds to China occasionally received them. The robes were embroidered with up to twelve symbols (solely for the emperors), the most prominent being the dragon. Robes with the fiveclawed dragon were reserved for the emperors and princes while officials and foreign envoys were accorded the four-clawed dragon. So-called mandarin squares also served to differentiate social status. Those badges worn on the front and back of costumes used animal or bird symbols to distinguish among various levels of civilian and military officials.

Ming craftsmen also introduced new designs and shapes in lacquer, cloisonné, and jade. As with porcelain, they borrowed some of these motifs and forms from other media and adapted them to the needs of their own materials. They adopted and altered motifs and forms from as early as the Shang dynasty, fitting in with Ming conservatism, but they also introduced elaborate designs and unusual shapes.

Like the Ming decorative arts, painting consisted of a combination of close associations with tradition and of deviations from orthodox patterns. Painters centered at the court in Beijing tended to follow the traditional works, depicting birds and flowers designed to embellish the walls and ceilings of the palace buildings. Landscape painters modeled their works on those of the Southern Song masters Ma Yuan (1160 or 1165–1225) and Xia Gui (fl. 1195–1224). Technical perfection and decoration rather than individual creativity or expression were the painters’ principal concern. Supervised by eunuchs in the Bureau of Painting, court painters were reluctant to deviate from tradition for fear of incurring the wrath of their eunuch overlords. Yet when Tai Chin (1388–1462; one of the landscape painters who alienated the court and was compelled to return to his birthplace in Hangzhou) was freed from court restrictions, he founded the Zhu school of painting, which produced more flexible and more individual versions of the types of landscape represented by Ma Yuan and Xia Gui. Tai Chin’s followers and associates were more independent and thus less bound by tradition.

Nonetheless, the court painters in general blended with the conservatism and stagnation of much of the elite centered around the capital. Perhaps intimidated by the eunuchs, by officials, and by court standards, these painters produced conventional and, on occasion, trite works. Because deviation from the accepted models might result in reprisals or dismissal, most court painters remained within accepted norms.

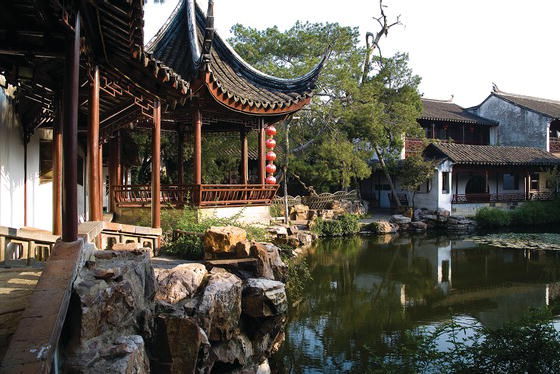

The painters of south China, particularly in the provinces of Jiangsu and Zhejiang, broke away from the accepted models, carving out new directions in painting. The garden culture they developed in such cities as Suzhou and Wuxi symbolized their elite lifestyle; it incorporated splendid pavilions and flowers adroitly situated near rocks and ponds to foster serenity and contemplation. Yet recent studies challenge this idyllic image and the idealized conception of the elite. According to their interpretations, the gardens provided the elite with a means of preserving wealth and avoiding taxation. Gardens offered a method of storing capital that the government could not touch. Production of useful and income-generating commodities rather than decoration or aestheticism was integral to the garden culture. However, increasing commercialization in the late sixteenth century led the elite to shift from a financial to a more aesthetic perception of the garden, partly to distinguish themselves from crass merchants. Unusual plants, rocks, and other deliberately unproductive landscapes began to supplement and substitute fruit trees and other economically viable pursuits in these gardens, where aesthetics overwhelmed agronomy. In this new vision, the owner was conceived of as a detached, reclusive gentleman who contemplated and enjoyed nature through his garden and scorned the commercial world and urban scenes and dabbled in the arts, including painting. A few went beyond mere dabbling and created great works of enduring value.

Figure 8.3

Humble Administrators Garden, Suzhou, Jiangsu province, China. © Henry Westheim Photography / Alamy