A History of China (49 page)

Read A History of China Online

Authors: Morris Rossabi

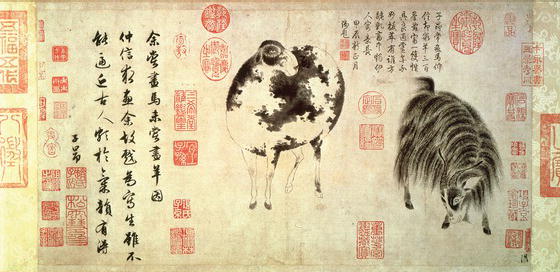

Figure 7.2

Zhao Mengfu (1254–1322),

Sheep and Goat

. Washington DC, Smithsonian Institution, Freer Gallery of Art. © 2013. Photo Scala, Florence

Naturally, most Chinese paintings were not produced to Mongol specifications and were not based on Mongol patronage. Some scholar-officials who did not serve the Mongols produced such traditional painting genres as landscapes, portraits, and bamboo depictions. Even those who assumed government positions under the Mongols continued to paint within the Chinese traditions. Zhao Mengfu, for example, emphasized a return to the ancients in painting, especially the Tang-dynasty models rather than the more recent Song-dynasty paintings. His depictions of horses fit into the models provided by the Tang. At the same time, he perceived his calligraphy to be as important as his painting, an attitude that the Mongols would not necessarily have appreciated. Yuan painters persisted in executing other traditional genres. Daoist painting flourished; it was neither derived from nor influenced by the Mongols. Buddhist painting owed some influences and motifs to the Mongol patronage of Tibetan monks. Mahakala, a deity often portrayed in Tibetan art, achieved greater prominence in Yuan art, and influences from India and the Himalayan regions may be seen in Chinese art during the Mongol era. An even greater deviation from the Mongol-employed painters was found in the work of artists who reflected despair at the current conditions and indirectly criticized the Mongol rulers. Images of emaciated horses representing Chinese Confucians who had been displaced by the Mongols and were powerless in this new society were one example of such denunciations of the Yuan-dynasty court.

The Mongols in China continued their ancestors’ patronage of craftsmen, first influencing ceramics. Although art historians traditionally discounted the role of the Mongols in the production of Yuan-dynasty ceramics, recent research has modified that view. The Mongols were not the potters who fashioned celadons or blue-and-white porcelains, but they had an impact in fostering the production of ceramics. The Yuan’s close relations with the Il-Khanate of west Asia led to the importation of cobalt blue into China. West Asian potters had, for some centuries, employed cobalt for pottery and, via the Mongols, the Chinese learned of the practice. As a Mongol commissioner supervised the kilns at Jingdezhen, the center of blue-and-white production, a Mongol role is indisputable. The Mongols also alerted Chinese potters to west Asian tastes, providing them with information about the shapes and decorative motifs that would appeal in the Islamic world. Their enforcement of migrations of craftsmen from one region of their empire to another facilitated the transmission of shapes and motifs.

The Yuan porcelain exported to west Asia catered to the clientele of that region. Jingdezhen and other sites produced massive plates, jars, dishes, and vases designed for this market. The Mongols knew that west Asian peoples characteristically placed their food on large plates for all the diners to consume. Mongol supervisors at the kiln sites recognized the west Asian preference for decoration and encouraged Chinese potters to depict plants, flowers, trees, dragons, phoenixes, and cloud collars, all derived from Chinese symbols. West Asian artists would themselves adopt some of these Chinese motifs in tile, pottery, textiles, and illustrations. To be sure, the Mongols were primarily interested in profit from the trade in Chinese porcelains, but their information and instructions had a significant aesthetic influence.

Figure 7.3

Yamantaka-Vajrabhairava with imperial portraits, ca. 1330–1332, silk and metallic thread tapestry (

kesi

), 96⅞″ (245.5) × 82¼″ (209 cm). New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Lila Acheson Wallace Gift, 1992. Acc. no.: 1992.54 © 2013. Image copyright The Metropolitan Museum of Art / Art Resource / Scala, Florence

The Mongols also played a role in textile production. Textiles, which were light and thus easily transportable, blended well with the Mongols’ migratory lifestyle. Because Chinese and central Asian weavers knew of the Mongols’ fondness for gold, they used gold thread for the clothing, Buddhist mandalas, and decorations they produced. The Mongols themselves took steps to foster the development of luxury textiles. They moved central Asian and Persian weavers to China to collaborate with Chinese weavers in producing the

nasij

, or cloth of gold, that they prized. More than half of the agencies they established in the Yuan Ministry of Works supervised the fashioning of textiles. Like nearly all craftsmen, weavers received tax reductions from the Mongols.

In sum, the Mongols in China contributed to the efflorescence of Yuan art. Because they were frequently the consumers of goods produced by craftsmen, artists and artisans had to cater to their tastes. Their enforced movements of artisans from one land to another resulted in considerable diffusion of motifs and technology. Aware of west Asian tastes, they offered guidance to craftsmen who wished to trade with the mostly Islamic populations in that region. The Yuan government offered tax exemptions for artists and craftsmen, allowing these artists to focus on their arts and crafts. The government also made substantial efforts to preserve the beautiful objects that were produced – in part through the Imperial Palace collections.

The Mongols appeared to be the supporters and protectors of many features of Chinese culture. They reinstated traditional rituals and ceremonies at court and restored most Chinese government offices (including the Hanlin Academy) as a center for the worthiest Confucian scholars; they recruited Chinese for their administration; and they built Chinese-style ancestral temples. They adopted the traditional Chinese policy of toleration or at the least benign neglect toward foreign religions as a means of ingratiating themselves with foreign clerics. They were ardent patrons of drama and the visual arts, which contributed to striking renaissances in these fields. In short, the Mongols showed great concern for the Chinese people and their culture.

ECLINE OF THE

Y

UAN

These positive developments characterized the first half of Khubilai’s reign, but dramatic events led to reverses in the last decade or so of his life. His principal wife died in 1281, and his son and designated successor predeceased him. These personal losses coincided with almost catastrophic problems of state. The construction of a capital city at Daidu and of roads and canals, the campaigns against Southern Song China, and expeditions against foreign states required tremendous expenditures. Khubilai chose a Muslim named Ahmad to raise the needed revenue, and the new minister fulfilled the government’s needs by enrolling more households on the tax lists, imposing higher prices on essential products on which the government had monopolies, and levying additional taxes on merchants. These policies, which were harshly implemented, alienated many in the Mongol and Chinese elites, and they responded by assassinating him and justifying themselves by accusing Ahmad of corruption and embezzlement of state funds. Ahmad’s successors were similarly dispatched, with some killed and some merely dismissed. Revenue problems plagued the remainder of Khubilai’s reign and persisted throughout the Yuan dynasty.

Foreign expeditions exacerbated these revenue shortfalls. Khubilai sent two expeditions against Japan, which had refused his orders of submission and had actually harmed his envoys. Bent on revenge, he did not consider the different environment he faced in sanctioning such a campaign. His troops had to be transported across rough and dangerous seas to Japan, and their remarkable advantage of a powerful cavalry would at least be partially neutralized. Koreans and Chinese were recruited to man the ships that took Mongol soldiers toward Japan. The first expedition was curtailed en route because of dangerous weather, but the Japanese were prepared for the second expedition in 1281, having constructed a lengthy wall all along the beaches where the Mongols would have to land. The Chinese sources report that the expedition, which consisted of 140,000 troops, set forth in two waves, one from south China and the other from the north Chinese– Korean border. The size of the force was no doubt exaggerated, but it nonetheless might have posed a threat to Japan had it landed. However, on August 15, a typhoon struck and sank quite a number of ships. Sailors and troops drowned, and those who had reached the shore found themselves without additional supplies and reinforcements and were no match for the Japanese samurai.

Although campaigns in mainland Southeast Asia were not as catastrophic, they were similarly costly and did not result in substantial gains. Expeditions in Champa and Annam (both in modern Vietnam) ended ambiguously, with offers by their rulers to present tribute to the Yuan court. The Mongols did not secure clear-cut victories. Their troops were not accustomed to the tropical and semitropical heat; they were vulnerable to new types of infectious and parasitic diseases; their horses were stymied in the forest regions; and guerilla warfare by the native inhabitants plagued them. Even more disastrous was the undertaking, with only limited naval expertise, of an expedition in Java (in modern Indonesia) in 1292, which faced the same difficulties as in mainland Southeast Asia. After a year of conflict, the Mongols withdrew.

In addition, continued fissures in the Mongol world were devastating for Khubilai. In 1287, a Mongol commander rebelled in Manchuria. This Nestorian leader, who was the Great Khan Ögödei’s grandson, posed such a threat that Khubilai, afflicted with gout and rheumatism, personally went onto the battlefield, leading a sizable force. Khubilai’s troops routed the enemy and killed its commander in the traditional Mongol way. Marco Polo described the execution:

He [the commander] was wrapped very tightly and bound in a carpet and there was dragged so much hither and thither and tossed up and down so rigorously that he died; & then they left him inside it; so that Naian ended his life in this way. And for this reason he made him die in such a way, for the Tartar said that he did not wish the blood of the lineage of the emperor be spilt on the ground.

1

At the same time, the Yuan’s border with central Asia was unsettled. Ögödei’s grandson Khaidu, still angered that his line had been replaced for the Great Khanate, challenged Khubilai throughout the 1280s and almost reached Khara Khorum, the former capital of the Mongol Empire. Khubilai’s forces pushed Khaidu away from Khara Khorum, but he persisted in his relentless raids and attacks from central Asia. Khubilai was more successful in crushing a revolt in Tibet. In 1290, his grandson virtually wiped out the Buddhist sect that had initiated the rebellion. Despite this victory, these outbreaks revealed disarray in Khubilai’s domains.

Two years after the Java expedition, Khubilai Khan died. A caravan carried his body to an undisclosed location, perhaps in modern Mongolia, for burial in what may have been an elaborate tomb. His alcoholic and culinary excesses following the deaths of his wife and son had contributed to illnesses and then to his death. The problems of revenue shortfalls and poorly planned and executed military expeditions attest to the inadequate policy formulations in the last years of his reign.

The Yuan court experienced repeated failures after Khubilai’s death. His grandson Temür legitimately succeeded Khubilai in 1294, but future successions were frequently contested. Struggles between the candidates often reflected the decades-long disputes between those Mongols who believed that they needed to accommodate to Chinese practices and institutions in order to rule and their brethren who emphasized an assertion of the traditional Mongol way of life and values. Such disunity weakened the Mongol elite, leading to repeated purges and assassinations of emperors. The most important crisis happened in 1328–1329, when two brothers fought for the throne. The early deaths of other emperors from natural causes added to the Yuan court’s instability. Bribery, a bloated bureaucracy, and substantial government grants to Mongol princes and Chinese officials contributed to chaotic conditions, which alienated the Chinese population. Reformers tried to limit these excessive grants to the Mongol and Chinese elites, but the bureaucracy and several emperors stymied them. The woeful shortages of revenue and the scandalously outsized payments to elites prevented the Yuan from preserving its military readiness and maintaining its infrastructure.