A History of China (46 page)

Read A History of China Online

Authors: Morris Rossabi

Paradoxically, the dynasty was open to new technologies and scientific investigations. Its seaborne contacts with Southeast Asia, India, and west Asia; the Neo-Confucian emphasis on investigation; and the government’s focus on civilian rather than military matters contributed to remarkable advances in the sciences. As the leading historian of Chinese science has written, “Whenever one follows up any specific piece of scientific or technological history in Chinese literature, it is always at the Sung [i.e. Song] dynasty that one finds the major focal point.”

8

Medicine and medical therapies attracted great interest. Acupuncture became widely used, and medical specialists produced an imperial medical text known as the

Recipes of the Department of Favoring the People and Harmonizing Preparation of the Taiping Era

(

Taiping huiming heji jufang

). A pharmaceutical text that emphasized the use of plants as medicines appeared, and a variety of studies on bamboo, birds, fishes, lichees, and flowering trees added to knowledge of botany and biology. New developments in bridge building (such as the transverse shear-wall and the caisson) and in hydraulics (such as lock gates) complemented striking advances in agriculture, including better seeds. Similarly, larger junks, the sternpost rudder, and the magnetic compass facilitated greater seaborne commerce. Less positive was the use of gunpowder for explosives, specifically for grenades and bombs ejected from catapults and cannons.

Shen Gua (1031–1095) was the most renowned writer on science in the Song and was one among its many remarkable figures. An unusually large number of extraordinarily capable officials, artists, and thinkers lived during the Song, and, like many of them, Shen was multitalented. Having passed the civil-service examinations and having supported Wang Anshi’s New Policies, he served in a variety of official positions, each of which required a move from one location to another. During his peripatetic life, he kept notes on the technological and scientific marvels he witnessed or learned about. He compiled his observations in a work entitled

Mengxi bitan

(

Dream Pool Essays

), which included sections on astronomy, mathematics, physics, chemistry, engineering, music, and other areas of study. It provided a summary of Song knowledge of these mostly scientific fields.

In sum, the Song witnessed remarkable achievements in science, technology, the arts, philosophy, overseas commerce, and the examination system, but political instability and an inadequate revenue base for government weakened the dynasty. Had the political excesses, including corruption, succession problems, and exploitation of the populace, been controlled, the Song would not have been as vulnerable to foreign attack. The Southern Song, in particular, with its sophisticated urban culture in the capital of Hangzhou, reached a level achieved by few civilizations. Marco Polo was entranced by its natural beauty, its lovely West Lake, the wealth of its inhabitants, its hospitals, its bathhouses, and its restaurants. He pronounced Hangzhou to be a place “where so many pleasures may be found that one fancies himself to be in Paradise.”

9

This cosmopolitan culture would face the most powerful steppe military adversary China had ever encountered. What is truly amazing is that the Southern Song managed to hold off this seemingly irresistible foreign force for more than four decades. Its wealth, its patriotic fervor, its military, and its cultural heritage sustained it and averted an immediate collapse.

OTES

1

Peter Bol, “Government, Society, and State: On the Political Visions of Ssu-ma Kuang and Wang An-shih” in Robert Hymes and Conrad Shirokauer, eds.,

Ordering the World: Approaches to State and Society in Sung China

(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), p. 180.

2

James T. C. Liu,

Reform in Sung China

(Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1959), p. 66.

3

Richard Barnhart, “Ching Hao” in Herbert Franke, ed.,

Sung Biographies: Painters

(Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1976), p. 25.

4

Michael Sullivan,

The Arts of China

(Berkeley: University of California Press, 3rd ed., 1984), p. 159.

5

Hsio-yen Shih, “Li Kung-lin” in Herbert Franke, ed.

Sung Biographies: Painters

(Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1976), p. 81.

6

Jacques Gernet,

Daily Life in China on the Eve of the Mongol Invasion,

1250–1276

, trans. by H. M. Wright (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1962), p. 18.

7

A. C. Moule and Paul Pelliot, trans.,

Marco Polo:

The Description of the World

(London: George Routledge & Sons, Ltd., 1938), p. 326.

8

Joseph Needham,

Science and Civilisation in China

I (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1961), p. 134.

9

Moule and Pelliot, p. 326.

URTHER

R

EADING

John Chaffee,

The Thorny Gates of Learning in Sung China

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986).

Patricia Ebrey,

Inner Quarters: Marriage and the Lives of Chinese Women in Sung China

(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993).

Jacques Gernet,

Daily Life on the Eve of the Mongol Invasion,

1250–1276

, trans. by H. M. Wright (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1962).

Valerie Hansen,

Negotiating Daily Life in Traditional China: How Ordinary People Used Contracts,

600–1400

(New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995).

Robert Hymes,

Statesmen and Gentlemen

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986).

Dorothy Ko,

Every Step a Lotus: Shoes for Bound Feet

(Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001).

James Liu,

Reform in Sung China: Wang An-shih and His New Policies

(Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1968).

Alfreda Murck,

Poetry and Painting in Song China: The Subtle Art of Dissent

(Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000).

Morris Rossabi, ed.,

China among Equals

(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988).

ART III

China and the Mongol World

[7]

M

ONGOL

R

ULE IN

C

HINA

,

1234

–

1368

A

FTER

the Khitans, Tanguts, and Jurchens came the Mongols, who differed from these other non-Chinese groups who dealt with the Song dynasty because they eventually conquered all of China. Paradoxically, the Mongols’ lifestyle and culture differed most markedly from those of the Chinese. Yet perhaps they had the greatest influence on China. To be sure, China had an impact on the Mongols, as its civilization attracted many of them. However, most Mongols did not become sinicized and retained their own identities.

Their identities, like those of the Xiongnu and other groups based in Mongolia, centered, in part, on their environment and traditional economy. A landlocked domain, a harsh continental climate, and severe winters confronted the Mongols in their native territories. Below-freezing temperatures in winter and spring and limited precipitation in summer, occasionally leading to droughts, impeded agriculture in nearly all locations and compelled the Mongols to rely on pastoralism. Even nomadic pastoralism was precarious because of dreaded winters with extraordinary amounts of snow and ice that prevented the animals from reaching the life-saving plants and grasses in the grazing lands. Hundreds of thousands or perhaps millions of animals perished under those conditions.

The Mongols migrated from one location to another to find water and grass for their animals. Two such movements per year were characteristic, but herders living in or near the Gobi desert might be compelled to move more frequently. Mobility was critical, especially during a bad winter, when the animals’ survival was at stake. Sheep, goats, and oxen provided food, fuel, clothing, shelter, and means of transport. Camels carried the Mongols’ belongings during their travels, and horses supplied the mobility required to round up the animals and to maintain a powerful cavalry – an extraordinary asset in warfare. Some Mongols supplemented their pastoral economy by hunting, and a few of them cultivated wheat, millet, and other grains, despite the short growing season.

Like pastoral nomads of the past, the Mongols needed to trade with China because of their precarious economy. They sought Chinese goods for their very survival, and their elites eventually desired silk and other luxuries in stable times. In turn, they supplied animals and animal products to the Chinese. When denied such commerce, they raided Chinese settlements to obtain the products they craved. Such engagements required larger and larger groups of Mongols and more sophisticated military organizations. The scale of warfare with China and among the Mongols themselves and various Turkic groups in Mongolia widened, devastating the grasslands and undermining the herders’ strategies for survival. The Mongols needed unity.

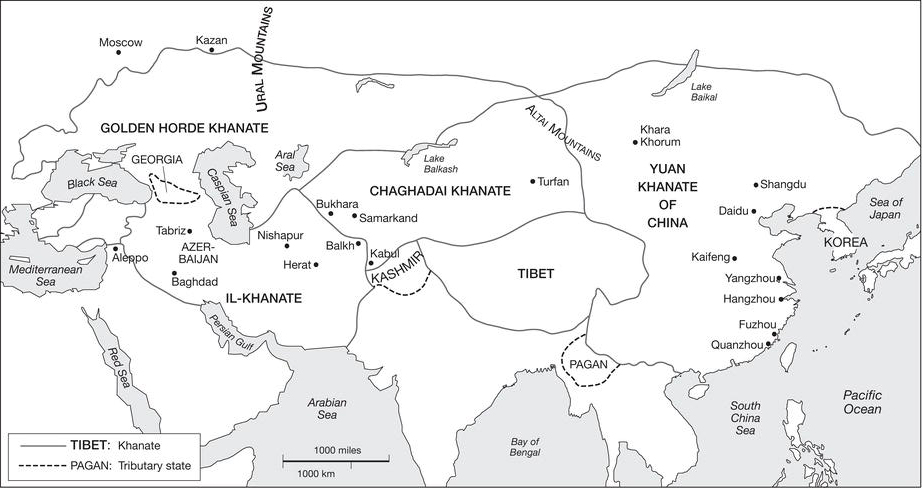

Map 7.1

Mongol Empire, 1279

ISE OF

C

HINGGIS

K

HAN

Temüjin (ca. 1162–1227) proved to be the charismatic and powerful leader who would unify the steppe peoples. The murder of his father when he was eight or nine years old was pivotal in his career. The

Secret History of the Mongols

, the only contemporary indigenous source on the thirteenth-century Mongols, writes that, with his mother and siblings, he was then forced to eke out an existence by gathering nuts and berries in the steppes. At that point, Temüjin recognized that he needed friends and allies to survive in this demanding environment; this was perhaps his most important insight. He forged one alliance after another, especially after he reputedly managed a hair-raising escape from a rival group that had imprisoned him. On occasion, he broke with his allies, defeated them, and incorporated some of his former enemies into his army, ensuring that they were personally loyal to him.

Other Mongol leaders had attempted to unify their people, but Temüjin developed more successful policies and practices. He chose his commanders based on merit, not on their aristocratic backgrounds. Those who were capable administrators or were courageous in battle were elevated into progressively higher positions. This policy of rewarding merit ingratiated him with his forces. His equitable division of spoils and rewards earned him additional support. After some notable victories, he assumed the title of “khan,” and once he had defeated all other Mongol leaders and had unified the Mongols, he was awarded the title of Chinggis Khan.

Chinggis capitalized on the Mongols’ military prowess to organize a powerful army. The Mongols required boys and many girls to participate in athletic contests, including horse racing, archery, and wrestling, which served as part of their military training. Chinggis also mandated that they take part in hunts as an additional aspect of their preparation for warfare. They learned how to shoot the Mongols’ composite bow, which had double the range of any other known in the world, while riding at full speed on their horses. Proficiency in the use of helmets, axes, and armor also contributed to their martial successes. In addition, Mongol tactics were highly developed. They placed felt puppets on horses to give a misleading impression of their numbers; they employed psychological terror by devastating a few towns and massacring the inhabitants in order to induce others to submit voluntarily; they feigned retreats to lure their pursuing enemies into a trap where their largest detachments were stationed; and they took great pains to set up supply lines and develop logistics. Chinggis demanded tight discipline. Commanders and ordinary soldiers who defied his orders or instructions were severely punished. Perhaps most important, the Mongols never set forth on a campaign without considerable intelligence information provided by merchants, defectors, and spies.

Another vital component of Chinggis’ successes as he ventured beyond Mongolia was his willingness to recruit foreigners. The Uyghur Turks, who voluntarily submitted in 1211, proved to be important subjects, as they had skills in commerce, administration, and finance. Even before their submission, Chinggis had commissioned one of his Turkic advisers to develop a Mongolian written language based on the Uyghur script. Chinggis also incorporated Turks into his army, and Turkic forces constituted a large segment of the forces for his son’s conquest of Russia.