A History of China (50 page)

Read A History of China Online

Authors: Morris Rossabi

Inattention to dams and irrigation works, predictably enough, led to floods and the spread of waterborne diseases. Unusually cold winters in the fourteenth century exacerbated the pressure on the Mongol rulers. Floods and changes in the course of the Yellow River in the 1340s were the final blows. Some Chinese died, and many had to abandon their lands. The changes in the course of the Yellow River interrupted the flow of grain from south to north China, a real threat for the dynasty. A Mongol reformer ordered the building of a new channel for the river to the area of Shandong province, a seemingly effective means of taming the waters. The government mobilized a large labor force and expended substantial resources for this construction project. The channel was built, but the expense in funding and in imposition of corvée labor turned out to be burdensome and generated greater Chinese hostility toward the Mongol rulers. The court defrayed some of its expenses by printing more paper money, leading to devastating inflation and a devaluation of paper currency.

The Chinese approved of one specific policy during this period. In 1313, the Yuan court decided to restore the civil-service examinations, and two years later it administered them. However, it suspended them on at least one occasion and did not mandate that fine performance on the examinations would be the only route to an official position. It also devised different and simpler examinations for Mongols and other non-Chinese and offered them a disproportionate number of posts in the bureaucracy. This policy reinforced the four-class system of Mongols, Muslims and other foreigners, northern Chinese, and southern Chinese, with the latter two often relegated to lower-level positions. Perhaps even more galling to the Chinese was the Yuan policy of favoring the military over the civilian authorities. Civilian scholar-officials had dominated in China for centuries. Thus the overturning of this long-held tradition offended many Chinese.

Banditry increased, and many Chinese found millenarian sects appealing. The White Lotus Society arose; this was a millenarian group that believed that the era’s chaotic conditions presaged the arrival of the Maitreya, or Future Buddha, with an ensuing last judgment in which the foreigners, the corrupt, and the exploiters would be punished. Such views prompted the society’s members to act in a major outbreak against the dynasty. In 1352, the so-called Red Turbans (founded by members of the White Lotus), identified as such due to the color of their headgear, initiated a rebellion that was surprisingly successful. Three years elapsed before the Yuan suppressed this millenarian movement. The inadequate Yuan response finally led to attacks on large local estates and government offices, leading eventually to the dynasty’s collapse in 1368.

EGACY OF THE

M

ONGOLS

Despite its inglorious end, the Yuan performed the invaluable service of linking China up with many areas of Eurasia. China and Europe had their first direct contacts with each other. European merchants, envoys, missionaries, adventurers, and craftsmen arrived in China, while at least one person born in China, a Nestorian Christian named Rabban Sauma, traveled to Constantinople, Naples, Rome, Paris, and Bordeaux. In 1245, the pope dispatched the Franciscan John of Plano Carpini to urge the Mongols to cease and desist from further incursions in Europe and to convert to Christianity. In 1253, the Franciscan William of Rubruck reached the Mongol encampments with a similar message. Although the Mongols rejected both pleas, the two Franciscan emissaries returned to Europe with valuable reports on their travels and observations, which, in turn, helped to prompt Genoese and Venetian merchants to travel to the central Asian, Indian, and Chinese sites the emissaries described. A sufficient number of traders journeyed to China for a fourteenth-century author, Francesco Balducci Pegolotti, to be able to provide a detailed itinerary, with an indication of distances from one town to another and with suggestions about the number of horses, camels, and men required for such trips.

Marco Polo was the most famous European of mercantile background to reach China. His father and uncle had visited China and had meetings with Khubilai Khan, who invited them to return with one hundred learned Christians to proselytize for Christianity. The two brothers did not lure Christian companions but brought their twenty-one-year-old son or nephew Marco from Venice with them. Marco remained in China, at the court or on travels throughout the country, for sixteen years. He departed from China in 1291 to escort a princess sent by Khubilai to marry the Mongol ruler of west Asia. In 1298, the Genoese captured Marco during a war with Venice. Fortunately for history, Marco was in a prison with a storyteller named Rusticello, who collaborated with him on a volume describing Marco’s journeys and observations. The account provided a vivid description of China and in particular of Khubilai. Marco was deeply impressed with both Daidu (or modern Beijing) and Hangzhou, the capital of the former Southern Song dynasty and the world’s most populous city. He did not mention bound feet, tea and teahouses, or the Chinese writing system, which has caused a few to question whether he actually reached China. However, the details he provides about events at court, Shangdu (or Xanadu), Daidu, the circulation of paper money, and the use of coal for heating tally well with Chinese sources. Although Europeans initially doubted Marco’s account, they eventually accepted it as an accurate description, which prompted them to seek a sea route to Asia.

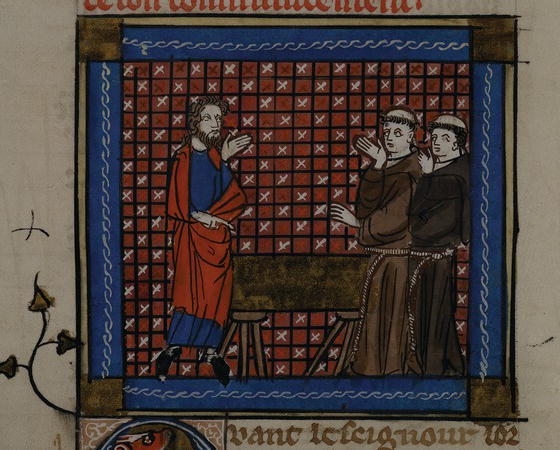

Figure 7.4

Khubilai gives the Polo brothers a golden passport. Image from

Le livre du Grand Caan

, France, after 1333, Royal 19 D. I, f.59v. © British Library Board / Robana

The travels of the Nestorian Rabban Sauma attest to the attempted political links between Europe and Asia. Rabban Sauma had departed from Daidu to undertake a pilgrimage to the Holy Lands. Arriving in the Il-Khanate, in present-day Iraq, he found that Muslims controlled the Holy Lands, which would prevent him from achieving his religious objective. He remained in west Asia until the Mongol ruler chose him for a delicate diplomatic mission. The Mongols proposed an alliance with the Europeans to attack the Mamluks, the major Islamic dynasty in the region and the occupiers of the Holy Lands. Rabban Sauma met with the pope and the kings of France and England, but his visit did not lead to collaboration. Nonetheless, the very idea of such cooperation reveals the scope of intersocietal contacts and the development of a true Eurasian history.

During the Yuan, China was influenced by Eurasia. It generally benefited from the technological, religious, scientific, and commercial relations with west Asia and Europe. The western countries began to acquire knowledge about China, and the Chinese came to be better informed about west Asia. Maps from this period attest to China’s great knowledge about the lands to its west. The Mongols of the Yuan maintained a strong relationship with the Mongols of west Asia and thus exposed China to developments in that part of the world. Although the Ming, the Chinese dynasty that replaced the Mongol Yuan, sought a more isolationist policy, it could not divorce itself from the world. From the Yuan period on, China was inextricably bound up with its neighbors, as well as faraway places in the west.

OTES

1

A. C. Moule and Paul Pelliot, trans.,

Marco Polo: The Description of the World

(London: George Routledge & Sons, Ltd., 1938), p. 199.

URTHER

R

EADING

James Cahill,

Hills Beyond a River: Chinese Painting of the Yüan Dynasty,

1279

–

1368

(New York: Weatherhill, 1976).

William Fitzhugh, William Honeychurch, and Morris Rossabi, eds.,

Genghis Khan and the Mongol Empire

(Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2009).

John Langlois, ed.,

China under Mongol Rule

(Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981).

Morris Rossabi,

Khubilai Khan: His Life and Times

(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988).

Morris Rossabi, ed.,

The Travels of Marco Polo: The Illustrated Edition

(New York: Sterling Publishers, 2012).

Naomi Standen,

Unbounded Loyalty: Frontier Crossing in Liao China

(Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2007).

M

ING

: I

SOLATIONISM AND

I

NVOLVEMENT IN THE

W

ORLD

,

1368–1644

Opening to the Outside World

A Costly Failure

Conspicuous Consumption

Arts in the Ming

Neo-Confucianism: School of the Mind

A Few Unorthodox Thinkers

Ming Literature

Buddhism: New Developments

Social Development and Material Culture

Violence in the Sixteenth Century

Fall of the Ming Dynasty

T

HE

parlous economic conditions of late Yuan exacerbated the earlier dormant ethnic antagonisms and resulted in banditry and full-scale rebellions. Economic upheavals opened the floodgates to a wide variety of rebel groups, all of whom tried to galvanize the support of the dispossessed and pauper populations. Yet the rebel leaders represented diverse constituencies and had different objectives. Each attempted to identify with the oppressed populace and assumed a strong antiforeign stance. Nativism had its appeal in a country controlled by foreigners for almost a century, not to mention the four centuries of alien rule endured by north China.

The White Lotus Society, one of the most powerful rebel groups, grew out of a secret religious organization. It was ecumenical and incorporated elements of Buddhist, Manichean, and Daoist beliefs; it gathered together many of the discontented; and it promised the destruction of the Yuan dynasty with the arrival of the Maitreya, the Buddha of the Future. This millenarian movement depicted the Maitreya as representing the liberating force that would overcome the decay of the Law, which had resulted in the evil and corruption dominating the world (the decay that was associated with the Mongols). First organized as a cohesive sect by a Buddhist monk, it spread quickly beyond the monasteries and attracted lay leaders who could marry, thus assuring greater continuity for the movement. Its growth also may have been stimulated by its tolerance for lay leadership. Traditional Buddhist sects were dominated by monks, and laymen played a relatively passive role in these organizations. In contrast, laymen were accorded considerable authority in this new organization. Acceptance of women into the sect was another unique feature of the White Lotus movement. Members initially met for religious assemblages, usually focusing on the means of achieving salvation, but soon the White Lotus assumed secular functions, serving as a mutual assistance group.

Map 8.1

Ming China

Its ideology, which provided a splendid vehicle for insurgencies against established authority, and its secular activities, which created a strong sense of community, had generated repeated government attempts at suppression. The government had already quashed the White Cloud Society, another dissident Buddhist sect; it had been easily dispersed in part because it had not truly branched out into the secular world and attracted laymen. The Yuan banned the White Lotus Society; yet it survived and in fact flourished, partly because it was ecumenical and incorporated elements from Daoism, Manicheism, and folk religion. Moreover, as the Yuan floundered and declined, leaders of the White Lotus Society took up the cause of resistance against the discredited and increasingly despised Mongol rulers. After some unorganized and ineffective outbreaks, they finally but briefly coalesced around a child named Han Liner, who was purported to be a direct descendant of the Song imperial family and was proclaimed as the first emperor of a newly restored Song dynasty in 1355. Some of the White Lotus leaders started another rebel movement, known as the Red Turbans because of the red headbands they wore. Although they recruited a sizable force in the Huai River areas north of the Yangzi River, lack of unity plagued them. Without centralized leadership, they could not mount a devastating challenge to the Yuan.