A History of China (54 page)

Read A History of China Online

Authors: Morris Rossabi

The most renowned among them formed the Wu school of painters. Shen Zhou (1427–1509), a wealthy gentleman who did not serve as an official, lived in semiretirement and began to paint landscapes in the style of the Yuan reclusive painters. He imitated the Yuan painters in rejecting government service, although they had the additional motivation of unwillingness to work for foreign conquerors. His scrolls and album leaves reveal the same simplicity as some of the Yuan landscape painters. However, unlike them, he occasionally populated his landscapes with small figures, lending them a greater sense of humanity. Several decades later, Wen Zhengming (1470–1559) painted landscapes in his own style; however, as important were his poems and prose works, many of which deal with gardens. His paintings and writings, which in part reflected his eremitism, contributed to the garden culture and to the conception of nature as a source of solace for the elite who failed to become officials or were rejected for government service. He offered a vision of a withdrawal from the hurly-burly of official or commercial life and a concern for personal cultivation and lofty pursuits.

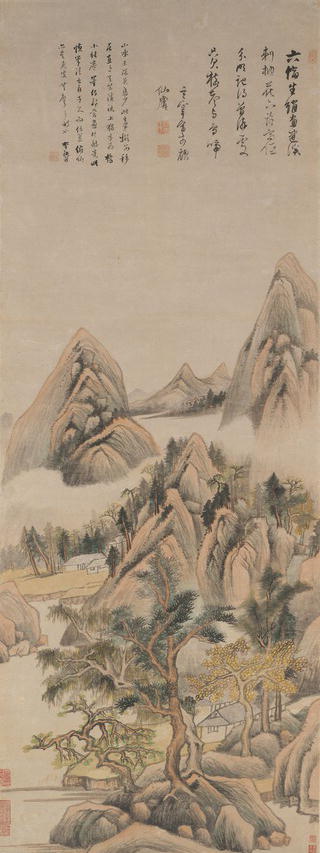

Figure 8.4

Dong Qichang (1555–1636), Reminiscence of Jian River, ca. 1621, hanging scroll, ink and color on paper, without mounting: 49

5/16

×18

9/16 ”

(125.3×47.1cm); with mounting: 102×24

9/16 ”

(259.1×62.4cm). New Haven (CT), Yale University Art Gallery. Leonard C. Hanna, Jr., B.A. 1913, Mrs. Paul Moore, and Anonymous Oriental Purchase Funds. Acc. no.: 1982.19.2. © 2013. Yale University Art Gallery / Art Resource, NY / Scala, Florence

It was left to Dong Qichang (1555–1636) both to embody and to provide an intellectual rationale for the literati in painting. A painter and calligrapher, he made a clear-cut distinction between the court painters and the literati artists, the latter of whom were freer from most restraints. They could, for example, paint landscapes more creatively and spontaneously than could the more rule-bound artists. Free both from the court and from the pecuniary concerns of the market and entrepreneurs, they could afford to explore the meaning of nature through art and to invest their explorations and insights with Confucian values. Dong classified those painters as part of the Southern school and the court painters as part of the Northern school, making a definite demarcation between the two. He perceived the independent and more scholarly painters of the Southern school to be superior to those attached to the court and those of the Northern school. The corruption and decline of the Ming court no doubt bolstered Dong’s negative views of those associated with the dynasty.

EO

-C

ONFUCIANISM

: S

CHOOL OF THE

M

IND

Developments in Ming thought mirrored the paradox of Ming political stagnation and commercial dynamism. Neo-Confucianism embraced both conservatives and innovators and both orthodox thinkers and creative individualists. Toward the end of the Ming, some thinkers even challenged Neo-Confucianism, offering scathing criticism of the status quo.

Ming Neo-Confucianism has traditionally been associated with Wang Yangming (1472–1529), who surely delineated the parameters of thought in the dynasty. Wang’s views are embodied in the life he led. In his works, he emphasized the strong links between moral cultivation and practical action. Thus, his active career as an official represented the fusion of meditative and social involvement. He believed that the meditative search for truth should not be equated with study of orthodox texts, even the Confucian writings. Although these works ought not to be discounted, they did not have a monopoly on the truth. Influenced by Chan Buddhism, Wang emphasized the “mind and heart” (

xin

) as the fount of knowledge, which could be achieved through looking within oneself, not through intensive study of authoritative Confucian classics. He challenged Zhu Xi’s School of Neo-Confucianism, which had focused on investigation of the external world as a means of obtaining knowledge.

The mind, which Wang equated with

li

(principle), was the final arbiter of truth, partly because the operation of the world mirrored that of the mind. True knowledge of the pure mind ought to be the major objective of those seeking enlightenment. Wang himself attempted to achieve sagehood and to instruct others in how to do so. Like the stereotypes of other Confucians, Wang had an optimistic view of mankind. He believed in the essential goodness of human beings and asserted that the mind could lead to this innate goodness of the individual. Thus, each individual could aspire to sagehood. Indeed, the mind contained the knowledge of goodness, but the path to such purity required considerable effort to overcome hurdles en route. Once such impediments as selfishness and acquisitiveness had been cast aside, the individual could reach the ideal of sagehood. No doubt Chan Buddhism influenced Wang in his disdain for external sources of wisdom, for constant study of Confucian texts, and for careful analysis of logic or experimental knowledge. His emphasis on looking within one’s own mind in attaining sagehood resembled the Chan Buddhist concern with intuitive attempts to achieve sudden enlightenment.

What distinguished Wang from Chan Buddhism was his belief in the fusion of knowledge and action. Unlike Chan, which focused specifically on meditation as the road to knowledge and enlightenment, Wang accorded action as crucial a position as knowledge. Knowledge could not be said to be understood unless it informed the individual’s action. The two were part of the same continuum. Knowledge needed to be translated into action to be considered true insight. Separation of knowledge and action revealed a lack of understanding. If knowledge and action diverged, the individual did not really “know.” For Wang, knowledge could not be separated from action, and his active official career testifies to his view of the fusion of the two.

Wang’s involvement in the politics of his time provided a model for officials. Scholars whose objective was the pursuit of knowledge had a rationale for undertaking positions as bureaucrats. They did not need to shy away from official careers because knowledge was intertwined with action. Because sagehood was predicated on such involvement, scholar-officials received justification for their roles in government. Such an approach jibed with the scholar-officials’ need for a rationale for public involvement yet offered tranquility through its emphasis on the clear and peaceful mind as the source of knowledge.

Although Wang was the dominant philosopher of his era, several who were influenced by his views charted new courses in thought. They also diverged from orthodox Neo-Confucianism or at least introduced Buddhist and Daoist beliefs into their conceptions. Each of these thinkers questioned the authority of the Confucian classics and suggested few limits on self-expression. Wang Gen (1483–1541), one of these thinkers, took Wang Yangming’s exaltation of the mind seriously and was, in particular, attracted by the great philosopher’s view that the mind superseded conventional morality concerning good and evil. The younger disciple, deriving from a nonelite family of salt producers, expanded upon Wang Yangming’s ideas to offer a greater threat to conservatism. Identifying with ordinary people, he concurred with Wang Yangming’s conception of the potential sagehood of all men. However, Wang Gen went one step further in advocating liberation of the common man so that he could achieve his potential – a clear challenge to the Confucian emphasis on the individual’s duty to society and on his obligations to the network of relationships in which he was embedded. However, he did not translate his seemingly egalitarian ideas into policies that might influence the court. Instead he lectured to and taught a wide array of disciples, not limiting himself to students preparing for the civil-service exams. He and Wang Ji (1498–1583) were considered to have founded the Taizhou school of Wang Yangming’s brand of Neo-Confucianism. Unlike Wang Gen, Wang Ji passed the civil-service exams and obtained the

jinshi

degree. Meetings and dialogues with Wang Yangming had a more pervasive influence. Although he served in government early in his career, he eventually retired when his ideas aroused corrupt or conservative officials to criticize him. He spent the last years of his life refining and supplementing Wang Yangming’s ideas. He, too, emphasized sagehood but asserted that it lay in faith in the mind. This devoutness would be construed as tantamount to religion, and Wang stressed, in particular, inner enlightenment and proper breathing techniques, deliberately relating his views to Daoist and Buddhist beliefs and practice. This digression from orthodox Neo-Confucianism left him vulnerable to criticism from Confucians, but gained him the respect and adherence of many Daoists and Buddhists.

The dramatic economic and social changes of the late Ming influenced the intellectual currents of the time and gave rise to unconventional thinkers who diverged from the prevailing Neo-Confucianism. Rural markets had developed amid a growing commercialization of the economy. Greater specialization in crops spurred the economy, as did the large quantities of silver imported into China. Prosperity, in turn, provided more leisure time and greater opportunities for an increase in literacy. Advances in printing offered access to a growing corpus of written materials, and publishers catered to the newly literate audience by issuing practical handbooks, short stories, and abbreviated and less difficult versions of the Confucian classics. Woodblock printing had developed earlier and a printed version of a Buddhist sutra dated 868 has been found, but the Song through the Ming dynasties witnessed an expansion in the number of printed works.

EW

U

NORTHODOX

T

HINKERS

Several thinkers responded to these changes, deviating from the concerns of traditional Confucian orthodoxy. Liu Kun (1536–1618) emphasized practical knowledge in contrast to the often arcane theorizing of some of the Confucian philosophers. His works concerned proper local organization, the education of all (not merely elite) children, and the value of commerce and merchants – decidedly un-Confucian sentiments. Writing in the colloquial style, he reached a wide audience, including women and ordinary individuals from nonelite backgrounds. He Xinyin (1517–1579), another unorthodox thinker, challenged the most basic Confucian institution, the family. Echoing the theories of universal love espoused by Confucius’s opponent Mo Zi, he criticized the family unit as parochial and limiting. He also defended free and unimpeded discussion, which contested all orthodoxies. His outspokenness and his ideas resulted in his detention in a prison, where he was killed.

Li Zhi (1527–1602) was the most unorthodox of these late Ming thinkers. Born into a merchant family, he took and passed the second level of the civil-service exams and had a two–decades-long minor career as an official. He then retired from government and started to study, write, and lecture on his novel ideas. An unrelenting critic of the orthodoxy of his time, Li enraged many traditional Confucian thinkers, and his heretical views aroused the hostility of officials, leading to his arrest for “immoral” and “subversive” ideas and behavior and to the suppression and destruction of his publications. While in prison, Li committed suicide.

Li Zhi’s criticisms of Confucianism stemmed, in part, from what he perceived to be its conservatism. He insisted that schools of thought needed to change with the times. Ideas and institutions had to adapt to ever-changing circumstances, but Confucianism had not been modified to conform to such changes. Li himself was fascinated with the novel, the latest literary genre, and wrote annotations for two such works of fiction. He actively sought to promote social change, championing the rights of women and the lower classes (groups who suffered as a result of the turmoil of the late Ming). His own outsider status, deriving from a commercial Muslim background, may have contributed to his empathy for other Chinese who were not part of the elite.

ING

L

ITERATURE

Developments in Ming literature, including the essay form, reveal the same dissatisfaction with orthodoxy and the social system. Growing commercialism and a larger printing industry (which catered to the growing number of literate individuals) provided fertile ground for popular writings. Printing establishments sprouted in the cities of Suzhou, the Southern Song capital of Hangzhou, and Nanjing, supplementing the earlier printing center of Fujian. The audience for works that offered practical advice was sizable. Morality books, which prescribed proper behavior and etiquette, were popular, particularly among the newly wealthy merchants. Copies of the notes of students who prepared for the civil-service exams, as well as model exam papers, had a substantial audience. Story books, encyclopedias, and simple commentaries and explications of the Chinese classics also sold well. Woodblock prints began to appear and found an appreciative clientele. Hu Jingyan (1582–1672) achieved the greatest successes in the production of these color prints, depicting flowers, fruits, and rocks. His remarkable collection of prints inspired other, more worldly artists to dabble in erotica. Albums filled with erotic prints began to appear on the market in late Ming times. The prints (illustrated in black, blue, red, green, and yellow, with each color used for a specifically designated part of the body or dress) offered depictions of nudes, suggestive erotic scenes, and explicit bedroom venues with half-dressed lovers. Such depictions, which occasionally illustrated Daoist conceptions of the conservation of male sexual energy and the masculine absorption of the female

yin

element during sex, had a considerable vogue, challenging Confucian orthodoxy.