A History of China (29 page)

Read A History of China Online

Authors: Morris Rossabi

ART II

China among Equals

[5]

R

ESTORATION OF

E

MPIRE UNDER

S

UI AND

T

ANG

,

581

–

907

Disastrous Foreign Campaigns

Origins of the Tang

Taizong: The Greatest Tang Emperor

Tang Expansionism

Irregular Successions and the Empress Wu

Tang Cosmopolitanism

Arrival of Foreign Religions

Glorious Tang Arts

Decline of the Tang

Tang Faces Rebellions

Uyghur Empire and Tang

Tang’s Continuing Decline

Suppression of Buddhism

Final Collapse

Efflorescence of Tang Culture

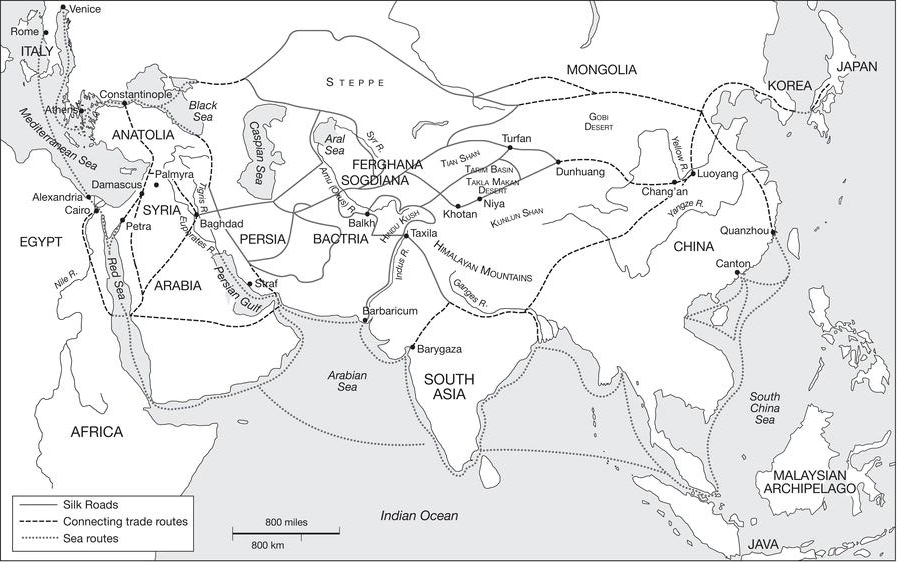

C

HINA’S

unification in the late sixth and early seventh centuries led to one of the greatest periods in Chinese and indeed world history. The Tang dynasty (618–907) – which emerged after almost four centuries of misrule, warfare, lack of a centralized government, and diminution of trade and tribute with the outside world – proved to be a quintessentially prosperous, powerful, and culturally productive era. The dynasty devised the administrative structure the Chinese would employ, with some variations, until the collapse of the imperial system in 1911. It began to recruit officials through competitive civil-service examinations, a characteristic feature of Chinese civilization. Its cosmopolitanism attracted, via the Silk Routes and maritime trade, numerous merchants, entertainers, soldiers, missionaries, and envoys who exposed China to foreign religions, music and dance, products, medicines, animals, and technologies, contributing to the dynasty’s resplendent culture. Simultaneously, China began to transmit paper, silk, tea, and other goods to numerous regions in Asia.

Map 5.1

Silk and sea routes in traditional times

China’s own creativity, as well as borrowings from foreign areas, contributed to this efflorescent culture. Poetry, tricolored ceramics, sculpture, architecture, and the other arts and literature reached extraordinary heights. The development of political and economic institutions set the stage for this dazzling culture. Military and political unification was the first step in devising the structure under which the arts, literature, and technologies flourished. This era began with a short-lived but important dynasty, the Sui.

UI:

F

IRST

S

TEP IN

R

ESTORATION

Yang Jian (541–604), the founder of the Sui dynasty, was descended from an aristocratic family of officials who had served the non-Chinese dynasties during the period of disunion. In hindsight, his upbringing proved to be ideal for a unifier of China, whose people had become exhausted after three centuries of disorder and lack of unity. A Buddhist nun took charge of his early education until he was twelve. He then attended the Imperial Academy, where he was exposed to Confucian learning but also had time to devote to military training. His military prowess led, shortly thereafter, to an appointment in the army. At the age of twenty-four, he married the daughter of one of the heads of a leading non-Chinese family, the Dugu. The young man now had links with the most powerful forces in China: the traditional aristocracy, the Buddhist monasteries, the Confucian scholarly elite, the military, and the non-Chinese peoples. Later his accession to power was facilitated by his daughter’s marriage to the heir apparent of the Northern Zhou dynasty, which offered a vital association with an imperial family. When the heir apparent died in 580, Yang Jian declared himself regent, then systematically murdered the princes of the Northern Zhou. In the following year, he proclaimed the founding of the Sui dynasty, with himself as Emperor Wen. Using his various associations, he suppressed opposition and within the decade had occupied and unified much of China. The culmination of his efforts was his conquest of the state of Chen in 581.

The question he now faced was how to rule a China that had been fragmented for over three hundred years. Recruitment of a loyal and effective group of advisers was essential. Emperor Wen first relied on his wife, one of the most influential empresses in Chinese history. Castigated in the sources as jealous and tyrannical, she played a vital role, nonetheless, in the government’s patronage of Buddhism, which turned out to be crucial in harnessing support for a unified empire under Yang Jian. The new emperor also recruited three competent men as counselors and administrators. Gao Jiong (d. 607), a Buddhist, devised a financial system that ensured revenues for the military and for construction projects; Yang Su (d. 606), a military commander, served as the dynasty’s enforcer, ruthlessly crushing opposition and thus giving the government the opportunity to establish order; and Su Wei (542–623), a civilian adviser, focused on civil administration, rituals, and a philosophic rationale for the new dynasty.

Although the dynasty’s initial successes were based upon its military force, its ability to govern depended upon its philosophical justification for rule and its creation of an effective government. The Sui was the first dynasty to use an eclectic ideology to legitimize its authority and to unify the various peoples within China. Its eclecticism revolved around its apparent support of and appeal to Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism. Confucianism, which had provided the ideological foundations of the Han, was deemed to be an insufficient stabilizing force after the collapse of the dynasty. Yet it was so closely identified with China that a prospective unifier needed to offer support. Emperor Wen, though a devout Buddhist, made overtures to Confucianism, first by restoring the Confucian court rituals (including music and dance) and by emphasizing such Confucian moral principles as filial piety and the Mandate of Heaven. Subsequently, he needed and selected Confucians as bureaucrats, since they tended to be the most educated members of the population. Yet he did not intend to rely exclusively on a corps of erudite Confucian scholars to serve as the main building block of his government. Instead he repeatedly expressed his desire to recruit pragmatic men who exemplified Confucian morality rather than academics without a practical bent. Yang Jian clearly sought Confucians who could offer tangible assistance in organizing a government, not a scholar who mouthed pious moral strictures.

Similarly, he patronized those elements of Buddhism and Daoism that could buttress his position and strengthen his government. For example, he tried to cloak himself in the mantle of a devout leader. He recognized that, if adopted by a large segment of the population, Buddhism could contribute to political unity. Since support from the major sects and monasteries would also help him consolidate his position, he provided funds for the construction of temples. These policies attracted many Buddhists to his cause. Daoism in its popular or, some would say, vulgar form had captured the imaginations of many Chinese, and Emperor Wen, though disdainful of excessive Daoist claims, still spoke favorably of the

dao

and its contribution to unity. On the other hand, he did not provide the same patronage to Daoist temples and monasteries that he had to Buddhist ones. In short, he attempted to bolster his claims to legitimacy by gaining the support of all three major systems of thought or religion in China.

Similarly, the governmental system that Emperor Wen and his advisers devised had elements of earlier institutions but was laced with some innovations. Like their use of the traditional philosophy of Confucianism as well as the newly introduced religion of Buddhism, the Sui rulers organized offices familiar to the Chinese population, along with new structures needed for the changed world in which they found themselves. They retained the old Han offices known as the Three Dukes but allowed them little real authority. Power was concentrated in the hands of the three central ministries: the Department of State Affairs, the Chancellery, and the Secretariat. The Department of State Affairs, consisting of six functional ministries – Personnel, Rites, War, Revenue, Justice, and Public Works – was the most important body. A principal deviation from the Han pattern was the elimination of the position of chancellor (one of the Three Dukes in Han times), possibly the central figure of earlier bureaucracies. Without a chancellor, power flowed into the hands of the emperor. Apart from the later addition of a chancellor, this structure, with some alterations, prevailed throughout much of Chinese history until 1911.

The officials the Sui selected to staff the major offices turned out to be, in some ways, unrepresentative of the new, unified China. Almost all were northerners; south China, which had experienced a population explosion after the fall of the Han and had been brought into the Chinese orbit, lacked much representation in the government. Like Emperor Wen, most officials derived from the Northern Zhou, and many were related to Emperor Wen and the son who succeeded him as emperor. Yet, in the lower ranks of the bureaucracy, Wen established merit as the principal criterion for selection. He sought to subvert the authority of powerful aristocratic families whose sons had had the inside track on positions in central and local government. Civil-service examinations were initiated and provided men to staff the eighth and ninth (lower ranks) of the bureaucracy, limiting still further the opportunities for the aristocracy to dominate.

The Sui thus sought to establish centralized rule over its lands, a policy that no dynasty in at least three centuries had been able to achieve. It granted the Ministry of Personnel the power to appoint local officials, preventing the irregular arrangements that had permitted aristocratic families to dominate local government. The court was determined to abolish the system of recommendations that had allowed the local aristocracy to control appointments and to vitiate the possibility of selection on the basis of merit. The court also mandated that the officials chosen by the Ministry of Personnel could not be sent to their birthplace, an additional check on the power of local oligarchies. Their tenure in any one position was limited to three (later four) years, which reduced the possibility that they would fall prey to the blandishments of the local elite.

The Sui also needed to assure itself of revenues to finance government projects and the military. It adopted the equal-field system developed by the Northern Wei as a means of land distribution and as a way of ensuring sufficient tax income. The underlying assumption of this system was that the emperor owned the land of China personally and that he distributed this land to adults who could cultivate it. When they were too old or sick to farm, the land would revert to the state and would be redistributed to young men who were capable of farming the land. In return for this grant, each farmer had to provide a grain tax and a donation of cloth, as well as about three weeks of corvée labor a year. Such land and tax policies required proper implementation. Yet local officials had no vested interest in promoting this more equitable system. Nor was the local aristocracy eager to abide by the system and thus relinquish the lands to which they laid claim. The result was massive disregard for the government’s land and tax directives. Many local officials, in collusion with aristocratic families, falsified land and tax records, removing considerable acreage from the system. Inadequate censuses and land registers naturally subverted the Sui court’s intention to establish a stable and equitable mechanism for land distribution that would also guarantee its revenue needs. In addition to the abuses engineered by local officials and aristocrats, the Buddhist and Daoist monasteries had received sizable tax-exempt estates, which further eroded the tax base. The equal-field system worked best on the land confiscated by the two Sui emperors from opponents and enemies. No aristocratic family could claim this land, and the government thus encountered fewer hurdles in distributing it according to the regulations.

Having devised the institutions needed to govern and having the requisite resources to set up these institutions, the Sui could now turn its attention to the actual mechanics of ruling. Emperor Wen had a new legal code enacted, which curbed the severity of punishments. He then sought to propagate this code within the officialdom, but yet again he was dependent in carrying out the laws on the officials themselves – bureaucrats who were, on occasion, corrupt and who lacked interest in proper implementation of the laws. Government also required a center for its operations. Recognizing the need for such a capital, which could bolster his legitimacy, Wen selected a site near Changan that had rich historical associations with the Chinese. His architects designed a walled city that met the requirements of imperial residences and bureaucrats’ offices and that blended with Confucian symbols and rituals.

The next step in the Sui’s consolidation of power entailed control over its frontiers and possible expansion to provide itself with a buffer zone. Repair of the walls (or so-called Great Wall) on the northern border was the first self-defense measure. The court then sent an expeditionary force that briefly occupied the kingdom of Champa (in modern Vietnam). At about the same time, a Sui army overwhelmed the Tuyuhun peoples who inhabited the lands to the west of the dynasty’s frontiers. Their principal adversary, however, was the Tujue, a group composed principally of Turkic peoples who controlled much of inner Asia, stretching from Mongolia to the borders of Persia. Having achieved unity under a khaghan (the title of the supreme ruler of the Mongols, often also termed a khan of khans) in the early sixth century, the Tujue had fragmented by the middle of the century into the Eastern Khaghanate, based along the Orkhon River in Mongolia, and the Western Khaghanate, which dominated much of western Turkestan. Emperor Wen attempted to control them through the Han dynasty tactic of divide and rule. By trying to exacerbate the tensions between them, he hoped to defuse the threat they posed to China’s lands. He pursued this policy throughout his reign and ensured Sui primacy or at least relative control over much of its northern frontiers.