A History of China (8 page)

Read A History of China Online

Authors: Morris Rossabi

The key figures in the elite were the king and the royal family. As the oracle bones attest, the king was clearly the main diviner, a ritual and religious function that at some early stage translated into secular political power. As he expanded his authority in the capital at Anyang, he instructed specific clans to settle in new towns and provided their leaders with tangible symbols of power, helping to legitimize their rule in these sites. The kings and their consorts derived from a small group of clans, among whom the royal succession rotated. Because primogeniture was not the norm, officials who were part of the elite advised the king on the choice of a suitable successor who could assume the religious, political, and military responsibilities. The king’s ritual tasks evolved throughout the dynasty but always involved offerings to the ancestors and earlier kings, as well as divinations concerning war, hunts, and other matters of importance. Depending on the era, kings also made offerings to deities associated with nature or performed rituals to produce more bountiful harvests.

Elite status conferred privileges and responsibilities on both men and women. Royal consorts played an active role in the public sphere. They could conduct sacrifices and act in the name of the king, and at least one took part in a military campaign. In short, they played active social roles rather than spending their lives in the shadowy private spheres of household and harem. Other members of the elite included princes, diviners, ministers, officials, and landlords who were granted land or walled towns by the king. Members of the elite had the right to accompany the king on hunts, often used to train the military, and to assume the responsibility of supporting him on military expeditions. By participating in the hunts, they had access to the animals bagged – a valuable resource for their own domains. In theory, the land accorded them was still owned by the king, and they were obligated to offer tribute to him. In practice, however, distance and time influenced the king’s ability to control them and to demand and receive tribute. The farther away their domains from the capital, the less leverage the king could have over them. Similarly, at times when weak monarchs were on the throne, they fulfilled their obligations with neither alacrity nor regularity. Yet their power derived from the titles that the king conferred upon them as lords over walled towns within the Shang state.

The princes and lords commanded the armies, but the social status of the military is not discernible from the sources. Naturally the king was the commander in chief of the state’s army, and the princes and lords led the military within their own domains – the military forces that could be mobilized were apparently sizable. Descriptions of the battles, of the captives, and of the human sacrifices of prisoners of war in the tombs of the elite attest to the participation of substantial numbers of soldiers in particular campaigns. The military achieved a degree of specialization, with specific units of archers, foot soldiers, and charioteers who used bows and arrows, halberds, and chariots.

Knowledge of the nonelite is even sketchier. The divination inscriptions describe what appear to be collectives of peasants who worked under the strict supervision of the king and lords. They worked together to farm the fields, served as soldiers, offered tribute, and were compelled to perform corvée labor. Although most were servile, labeling them “slaves” is an overstatement. Unlike slaves, most could not be bought or sold. To be sure, slavery existed in the Shang; prisoners of war were often enslaved and forced to work in the fields or were sacrificed at tombs of kings or lords. Yet the vast majority of the nonelite were not slaves, although they undoubtedly were accorded little status, were economically exploited, and were dominated by the kings and lords. As suggested earlier, artisans had a higher position in the social hierarchy, lived more comfortably, and had access to more goods than ordinary commoners. Specific clans dominated particular trades such as woodcarving, bronze casting, and jade carving, and craft production was often a monopoly transmitted from one generation to another.

Although records on finances are absent, it appears that the king collected taxes from all his subjects. He received tribute of grain, principally millet, from the peasants, who also sent cattle (for his divinations), sheep, and horses to the capital. During his hunts (and possibly tours of inspection), he also requisitioned supplies from the peasants for his entourage. The quantity of taxes levied by the king is not recorded, but it must have been sufficient to pay for military campaigns and the elaborate tombs and other material possessions of the royal household. Simultaneously, the king received goods that the artisans had fashioned. The furnishings at the royal tombs, as well as those of the elite, attest to the considerable number of bronzes, jades, and pottery items commandeered from craftsmen. Merchants surely played a role in transmitting grain and craft articles from the various towns to the capital and vice versa, but they are scarcely mentioned on the oracle bones. Cowry shells were used as currency, and the modern Chinese word for “merchant” (

shangren

) uses the same Chinese characters as “man of Shang.” Yet the paucity of data precludes efforts to assay the role of trade and the status of merchants during this era.

The available information, however, permits us to conclude that the population was divided into defined groups and classes. The king and the royal family were at the apex, with the monarch performing ritual functions (including divination), commanding military forces, and amassing considerable quantities of grain, craft articles, and other valuables. The lords to whom the king entrusted land for the construction of new settlements held sway over these territories, as well as over the inhabitants. They too received substantial amounts of the goods produced within their domains. Less privileged were the peasants, slaves, craftsmen, and merchants. Peasants did not own the land they farmed and turned over much of the produce to the king and the lords. Known as

zhongren

(multitude), they could be conscripted into the military or for labor service. Often captives of war, slaves could count themselves fortunate if they were employed to farm the land or to act as servants and unfortunate if they were selected to be sacrificial victims. Although craftsmen had a higher status and lived better than the

zhongren

and the slaves, the articles they fashioned were most often designed for the king and the nobility.

This generally stable social structure contributed to a popularly accepted conception of the uniqueness of Shang culture. Some archeologists asserted that its culture and artifacts were primarily indigenous. Even more significant was that the inhabitants of the Shang perceived themselves as a different people. They had, after all, developed a sophisticated culture, with a worked-out political system, a highly organized bronze industry, a unique burial system, and a written language. Their pictorially based written language, found mostly on the oracle bones and perhaps in some signs and symbols on ceramics, contributed, in large measure, to the Shang people’s feelings of identity. The language, with its initial associations with divination and religion, proved a powerful vehicle for the fostering of their sense of affinity.

With the growth of such feelings of identity, the Shang distinguished itself from other neighboring regions, which were sometimes adversaries. Most attacks against Shang territory originated from its north and northwest, and the final onslaught, which overwhelmed the dynasty and permitted the rival Zhou dynasty to take power, derived from the northwest. Competition for land and for control of mineral deposits and other natural resources provoked crises and conflicts between the Shang and nearby territories. Such hostilities bedeviled relations between these various states. Ironically, conflict may have resulted in interaction and borrowing among a few, which enlarged the territory in which cultural homogeneity prevailed.

OTES

1

K. C. Chang,

The Archaeology of Ancient China

(New Haven: Yale University Press, 4th ed., 1986), p. 310.

URTHER

R

EADING

E. J. W. Barber,

The Mummies of Ürümchi

(New York: W. W. Norton, 1999).

K. C. Chang,

Shang Civilization

(New Haven: Yale University Press, 1980).

K. C. Chang,

The Archaeology of Ancient China

(New Haven: Yale University Press, 4th ed., 1986).

David Keightley,

Sources of Shang China: The Oracle Bone Inscriptions of Bronze Age China

(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985).

Harry Shapiro,

Peking Man

(London: Allen & Unwin, 1974).

C

LASSICAL

C

HINA

, 1027–256

BCE

EUDALISM”?

Although the Zhou lasted longer than any other dynasty in Chinese history, its longevity may be deceptive. There was a sharp break in the dynasty, for in 771

BCE

it was compelled to move its capital. During the first phase, known as the Western Zhou, its administrative center was located in the Wei river valley, west of the modern city of Xian; in the succeeding phase, known as the Eastern Zhou, the capital was transferred to Chengzhou (near the present-day location of Luoyang), which the Western Zhou had used as a secondary capital. The remaining five centuries of Eastern Zhou rule witnessed a rapid deterioration in its ability to govern, leading to a chaotic struggle for power between areas reputedly under its jurisdiction during the so-called Warring States period (403–221

BCE

).

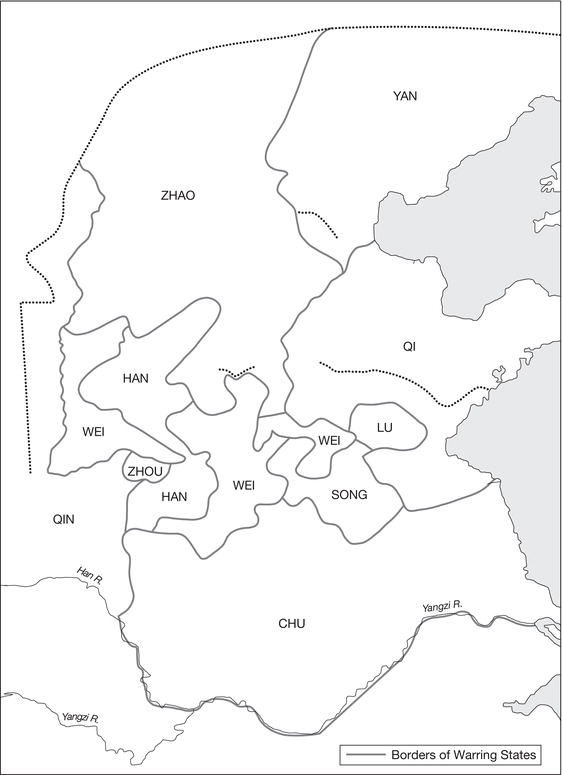

Map 2.1

Warring States-era divisions

The Zhou had from its inception set up a decentralized government, which some scholars identify as similar to the European system of feudalism. However, the concept of feudalism is also murky. In its simplest form, it consisted of a legal and military system based on a relationship between a lord and a vassal. A lord who owned land turned over possession of a portion of that land (known as a fief) to a vassal in return, principally, for military services. Their mutual obligations and rights entailed a pledge of loyalty to the lord by the vassal and a pledge of protection of the vassal by the lord. Peasants who worked the land on manors for the lords and vassals or in Church estates were also part of this feudal society. Yet there were so many variations of “feudalism” in Europe that some scholars have stopped using the term in relation to China. Thus, the Western Zhou may be best described as a society in which the local nobility often supplanted the kings as true wielders of power. The rudimentary levels of transport, communications, and technology clearly reduced the opportunities for centralization. Even so, the Zhou political system, particularly the Eastern Zhou, tilted further toward localism than such limitations would have mandated.

Decentralization stemmed from the initial Zhou conquests, though it should be noted that disentangling myth from reality concerning its early years is difficult. Part of the problem is that texts allegedly written in the Zhou actually derive from later periods. Many Chinese accepted the earlier dates. The sources all concur that the Zhou peoples traced their ancestry to Hou Ji, whose second name translates as “millet.” This semidivine figure reputedly instructed his descendants in the basics of farming. Inhabiting as it did the areas west of the Shang kingdom in the Wei river valley, the Zhou had often bellicose relations with its neighbor for several generations before their final confrontation in the eleventh century

BCE

. Despite these conflicts, the Zhou was influenced by the Shang. Designs and techniques of early Zhou bronzes and ceramics resembled Shang prototypes, and their rituals were often similar.

Culmination of the strained relationship occurred during the reigns of the stereotyped, almost legendary father-and-son monarchs, Wen and Wu of Zhou. The sources endow Wen (his name signifying “accomplished” or “learned”) with the attributes of a sage-ruler. Intelligent and benevolent, Wen believed in negotiations and compromise in relations with others and in governing his own people. His remarkable character paved the way for his son Wu (his name meaning “martial’) to battle with and overwhelm the Shang. The sources praise Wu for his military successes, but Wen represented the ideal. Even at this early stage in Chinese culture, civil virtues were more highly prized than military skills. The sources, for example, extol the Zhou for their magnanimity toward their defeated enemies. Instead of adopting a military solution and extirpating the Shang royal family, the leaders of Zhou gave them land in order to permit them to continue their ancestral rituals.