A History of China (5 page)

Read A History of China Online

Authors: Morris Rossabi

The earliest known sites can be found as far apart as southern Hebei province and eastern Gansu province, and several have been found in south China. The residences and cemeteries excavated in the northern areas share specific characteristics – round or square houses, underground storage pits, use of specialized stone tools including knives, axes, hammers, and mortars and pestles, and simple handmade red or brown pots. Pigs and dogs had been domesticated, and this may serve to explain why (in an indication of the vital role of the pig in early China) the Chinese character for “pig” placed under the character for “roof” came to form a new character meaning “family” or “household.” The dead were buried singly in individual graves and provided with pottery or stone tools. Many of the sites in south China are located in caves, again scattered across a wide variety of regions in the provinces of Jiangxi, Guangxi, and Guangdong. Judging from the tools found in these sites, the cave dwellers worked the land but also hunted and fished. Bones of deer, sheep, rabbits, and birds indicate the range of animals they hunted. Like their contemporaries in the north, they had domesticated the pig, and the large number of pig bones indicates the animal’s value to the inhabitants.

The Yangshao sites are doubtless the most renowned of the early Neolithic cultures. Discovered in 1921 by J. G. Andersson, they provide a wealth of data on the peoples and economies located in the area. Banpo village in the modern city of Xian is a typical example of these sites. Excavated by archeologists starting in 1953, the site has been turned into a well-arranged museum with helpful descriptions of the original layout of the village. Because it has been left in pristine condition, it provides a glimpse of Neolithic life. The discovery of the bones of various animals, including deer, raccoons, and foxes, confirms that that the Banpo villagers, like their counterparts in Paleolithic cultures, hunted for part of their sustenance. The uncovering of seeds from trees verifies that the inhabitants also gathered food. Yet their generally sedentary existence and their larger populations necessitated a steadier source of supply than hunting and gathering. Since agriculture offered greater control of their environment, the villagers turned to farming for most of their needs. Millet was their principal food crop, and rudimentary farm implements, such as hoes and spades, exemplify some of their technological sophistication. Fishing provided variety to their diet and appears to have been a significant economic activity, as evidenced by the numerous representations of fish on their pottery.

Banpo was a well-laid-out village. Its inhabitants placed their sturdy houses, which were either at or below ground level, at the center of the village complex. Plastered floors and walls, as well as roofs supported by wooden posts, gave an appearance of permanence to the dwellings. Adjacent to the houses were storage pits, with pottery containers often used as granaries, and enclosed areas for domesticated animals. A cemetery (in which more than a hundred skeletons of adults were discovered) and a kiln were located on the fringes of the village. A communal dwelling was found at the center of the village, and the doors of the individual dwellings opened out onto the center. The large number of infants and children buried in the cemetery and in burial urns near the houses attests to the fragility of life in this era.

Like most of the other Neolithic sites in the north, Banpo was situated near a tributary of the Yellow River. The nearby waters provided the foundations for agriculture. The river conveyed the fine grains of sand that had, probably for millennia, been transported from the Mongolian deserts. After the sand was deposited and weathered, it eventually formed the loess soil that made the land productive. Layers of loess soil deposited over thousands of years facilitated farming, partly due to the ability of the loess to absorb water, and the river provided the water to nourish the soil. However, the river could cause havoc to neighboring villages. Accumulation of substantial amounts of loess in the river could, on occasion, result in water spilling over the banks and flooding. Villages downstream felt the full energy of the river. The reaction to such flooding was simply to move to higher grounds to avoid the onrushing water. Later, substantial irrigation projects would be devised to control the river.

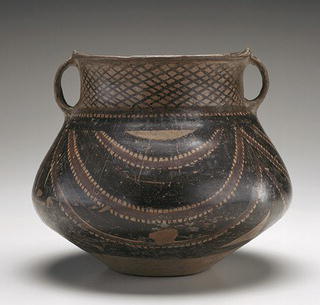

Figure 1.1

Ceramic urn, Gansu province, Neolithic period. Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, USA / The Bridgeman Art Library

Banpo’s inhabitants had made great strides in the production of pottery, which varied considerably in color, decoration, and shape. They used a red pigment to paint a large number of the pottery vessels, but not all were painted; some were gray or black. The shapes of the vessels, which were remarkably diverse, were often dictated by their use, from tripods for cooking to thin-topped but large-bodied jars for storage to both small and large bowls for food and for ritual observances. The decorative motifs were also varied, with geometric designs, realistic depictions of fish and deer, and abstract representations of fish and animals. These depictions of fish and animals reflected the continued significance of hunting and, particularly, fishing in the economy of the village. Symbols on some of the pottery may have indicated ownership or the sign of the potter and may have signaled the beginnings of a written language.

The village’s tools and ornaments were more numerous and diversified than similar artifacts of the Paleolithic era. Stone chisels, polishing tools, hoes, and spades supplemented the stone axes, knives, and arrowheads of earlier times. Antler needles, fishhooks, spearheads, and polishers showed significant improvements in technology. The fashioning of decorative items such as rings and beads made of jade and other semiprecious and precious stones indicated the development of an economy producing more than subsistence products.

The Banpo village and the original Yangshao villages were not the only north China sites of Neolithic culture. Since the 1920s, other such sites have been excavated in the provinces of Gansu (the so-called Painted Pottery Culture), southern Hebei, central Henan, and Shaanxi. They shared some of the same cultural and economic traits of Banpo, but there were nonetheless variations in the sizes of the villages, the types of pottery and stone implements, and the methods of burial. Such differences presaged a characteristic of much of Chinese history and a persistent theme in this book – the local deviations from central patterns or, later, from central government’s demands and laws.

South China also witnessed the development of early Neolithic cultures, but the early and late Neolithic sites found in the province of Shandong (in the northeast) were most closely related to the earliest true Chinese civilization. Like the Yangshao, the Dawenkou culture of Shandong, which originated later than the Yangshao culture, was based upon millet production, but its tools, pottery, weaponry, and crafts were more complex in design and in performance. In addition, excavation of the graves revealed growing complexity in social organization. A few were extremely elaborate, with exquisite pottery and stone implements, while most were bare or had relatively few furnishings. Such evidence points to a more hierarchical social structure. In addition, it is apparent that Dawenkou had been influenced by other Neolithic cultures. The borrowing of practices confirmed that the various Neolithic communities were in touch with and affected each other.

Figure 1.2

Ting tripod bowl, Longshan culture (third or early second millennium

BCE

) from Shandong province. The Art Archive/Genius of China Exhibition

The Longshan culture of Shandong, which succeeded the Dawenkou, was the culmination of the interrelationship of the earlier Neolithic sites. Relatively few Longshan villages have been totally excavated, but the ones that have reveal significant changes from Yangshao villages. The pottery, for example, was principally black and gray, differing from the painted pottery of the Yangshao. Most vessels were relatively unadorned, although some were decorated with incisions and appliqués. The tripods, jars, and other shapes characteristic of Yangshao were also found in the Longshan assemblages, but new forms, such as steamers and cups with handles, were introduced in the Shandong cultural complex. Stone and bone implements and weapons in both cultures were similar, but the preponderance of arrowheads and spearheads in Longshan indicated a greater concern for defense from troublesome outsiders.

The very concept of “outsiders” was a new formulation; it shaped some unique features of the Longshan and provided even sharper distinctions from the Yangshao. Defense against perceived or actual enemies heightened the Longshan villagers’ sense of identity and unity. They began to recognize that they shared certain beliefs, customs, practices, and institutions that clearly distinguished them from others. The most tangible manifestation of distinctiveness was the construction of walls around their villages, a practice that most Chinese cities would later follow. The Longshan village of Chengziya built the earliest known such wall, to an average height of about six meters. Defense was the paramount consideration for the villagers; yet the walls reflect an affinity of interests – familial, clan, and political – that required protection. The inhabitants of these walled villages sensed that they belonged together and were distinct from other groups.

In addition to stamped-earth walls, Longshan culture exhibited other features that would be found in the earliest Chinese dynasty. Longshan appears thus to be a direct link between the Neolithic era and the origins of Chinese civilization. Not only did Longshan and the earliest Chinese civilization build walls around their villages but they also both used the practice of scapulimancy. Diviners or community leaders burned animal scapulae to generate cracks that they would then interpret to foretell the future. These so-called oracle bones, pervasive throughout the Longshan sites, constituted a step in the development of the Chinese written language and yield invaluable information about the Shang, the first attested dynasty. They also reveal an increasing concern for rituals, which is also shown in the unusual animal-mask decorations on the distinctive black pottery, tools, and other objects and in the markedly different burials from those found in Yangshao sites. The Longshan devoted considerable resources to burials, which is an indication of increasing attention to ceremonies concerning an afterlife and of a more stratified social structure. A few burials in the cemeteries consisted of sizable graves with wooden caskets and numerous furnishings; a slightly larger number had a few caskets and some scattered goods; and the largest number had no caskets and no furnishings. It appears that the more elaborate the burial, the higher the socials status of the deceased.

Attention to rituals and ceremonies, together with walled villages and oracle bones, link Longshan to the earliest Chinese civilization; in addition, new materials for tools and weapons and clearer political and social distinctions relate this Neolithic culture to the first recognizable entity that can legitimately be called China. Objects made of copper and several bronze vessels, which were discovered in a number of Longshan sites, mark the transition from a stone-age to a metal-age culture. The Bronze Age dynasties were still at some remove, but the appearance of metal tools indicates technological advances on the path to the full-blown metallurgical centers of early Chinese civilization. Warfare and burial practices and other ceremonies point to demarcated territories and political groups and to a stratified society, still another step toward the first Chinese dynasty. Political power within the Longshan groups became more concentrated, and wealth varied considerably. Such differentiations presaged the social distinctions found at the early stages of Chinese culture.

Although Longshan was associated principally with the province of Shandong, other sites sharing the same characteristics were widely dispersed in the third millennium

BCE

. Farther to the south, around the modern cities of Hangzhou and Shanghai and other centers along the Yangzi River, archeologists have excavated villages exhibiting the same cultural features as the prototypical sites in Shandong. To the west, some villages inthe provinces of Shaanxi, Gansu, and Henan, associated with the Yangshao culture, gradually manifested traits of the Longshan, and their material culture and social differentiation resembled those of the Longshan. Even farther away, archeologists have uncovered Longshan-like sites as distant as Fujian and Guangdong in the south and the Liaodong peninsula in the north.