A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony (32 page)

Read A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony Online

Authors: Jim Aikin

Figure 7-38. An altered Phrygian mode in which the 3rd has been raised.

Earlier I noted that the Phrygian mode is seldom used in an unaltered form. But the second pentatonic scale shown in Figure 7-37 has the same lowered 2nd as the Phrygian. It also has an exotic-sounding augmented 2nd interval. Combining the two scales, we might come up with a scale like the one in Figure 7-38. If this scale has a name, I've never learned it, but it's quite useful in one specific instance: for soloing over the classic Spanish/flamenco progression shown in Figure 7-39. This works because the scale contains major triads on both the I and 611.

Figure 7-39. The scale in Figure 7-38 can be used for soloing over a l-611 progression. This scale could be further altered, depending on the desired musical effect, by raising the 7th step so that it can function better as a leading tone. In addition, a lowered 3rd (GI1 in the key of E) could be inserted between the 2nd and the major 3rd.

THE BLUES SCALE

The musical genre known as the blues developed in the early 20th century. Because its origins lie in the African-American communities of the Southern U.S., certain of the harmonic devices employed in the blues are probably descended from the indigenous folk music traditions of West Africa. Irrespective of where the blues came from, it has profoundly influenced American culture: The blues tradition gave birth both to early jazz and to early rock and roll. At the same time, blues music has remained a vital genre in its own right.

In Chapter Eight, we'll take a look at the standard chord progressions used in the blues. But no chapter on scales would be complete without a discussion of the blues scale.

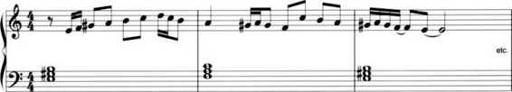

In its simplest form, the blues scale has the same form as the minor pentatonic. What makes this scale interesting is that when the blues chord progression changes from the I chord to the IV and the V, the scale doesn't change. Thus the notes of the scale have different harmonic implications, depending on which chord they're played with. Figure 7-40 illustrates this idea.

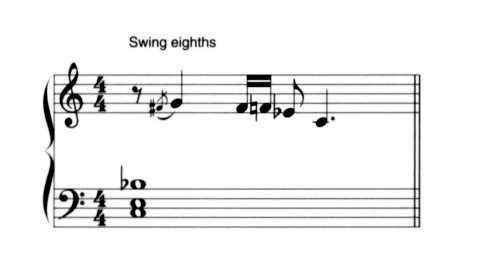

The minor pentatonic is often enriched with some extra notes, which are generally used as passing tones or appoggiaturas. The most frequently used extra tones are shown in Figure 7-41. Since the scale in 7-41b contains nine of the 12 notes in the chromatic scale, you might easily assume that in the blues scale almost any note can be used at any time. What's essential to understand about this extended form of the blues scale is that all of the notes are not created equal. Unlike a scale in classical music, the extended blues scale is never played by simply running up and down the scale. It's an inflected scale, which is a fancy way of saying that certain notes have particular relationships to other notes.

Figure 7-40. A 12-bar blues chorus in D (omitting the last two bars). All of the notes in this rather stiff but reasonably idiomatic blues melody are drawn from the D pentatonic minor scale. This results in some harmonic clashes that are characteristic of the blues. First, the augmented 9ths - or, if you prefer, minor 3rds - of the I and V triads are included in the scale: An Fb is played above the F# in the D7 chord, and a CC above the C# in the A7 chord. Second, the 4th is used freely above all three chords (G above the D7 chord, C above the G7 chord, and D above the A7 chord), which clashes with the major 3rd. Finally, above the A7 chord the Fq is a #5.

Figure 7-41. The pentatonic blues scale in Figure 7-40 can be expanded by adding the flat 5th, as seen in (a) here. This note is highly unstable harmonically, and always resolves either upward to the natural 5th or downward to the 4th. Whether it's spelled enharmonically as a sharp 4th or a flat 5th is a matter of taste. A more complete version of the blues scale is shown in (b). The major 3rd has been added, as have the two notes shown in parentheses. These notes most often function as secondary tones that resolve upward or downward. The minor 3rd (E6 in the key of C, as shown here) can be used either as a secondary tone tending upward to the major 3rd, or on its own. If the chord progression uses a minor I chord, the major 3rd will be avoided.

Figure 7-42. The sharp 4th in the blues scale (which can just as easily be notated as a flat 5th) is unstable, and resolves either upward to the 5th or downward to the 4th. This lick shows both types of resolution.

The sharp 4th step, for instance, is almost always followed by the natural 4th or the natural 5th. It's an unstable note, and has to resolve either upward or downward, as in the blues lick in Figure 7-42. In the same way, the 2nd usually resolves upward to the minor 3rd or downward to the root, and the 6th resolves upward to the minor 7th or downward to the 5th. A lick that illustrates these uses of the 6th and 2nd is shown in Figure 7-43.

If the major 3rd is used at all, the minor 3rd will probably be treated in the same way, as an unstable tone that resolves upward to the major 3rd. Above the N7 chord, however, the major 3rd of the scale would usually be avoided, because it would clash with the minor 7th of the IV chord.

Figure 7-43. Like the #4/65, the 2nd and 6th of the blues scale are secondary tones, and usually resolve to higher or lower tones.

The use of grace-notes in Figures 7-42 and 7-43 is typical of blues played on a piano. Guitarists and singers, however, and keyboardists who play synthesizers, can bend notes up or down, gliding smoothly from one tone in the equal-tempered scale to another. (Technically, a guitarist can only bend notes upward, but by picking the note after bending a string sharp and then letting the string fall back to its original fretted pitch, the guitarist can create the illusion of a downward bend.) Bending notes is an essential part of blues technique. Both the secondary notes shown in parentheses in Figure 7-41 and the main notes above and below them are often produced by bending.

Blues bends don't always change the pitch by an equal-tempered half-step. Sometimes a bend takes a while to move from one pitch to another, and the note may end before the nominal destination is reached - or the bend may fall back to a lower pitch without ever reaching the upper one. As a result, the minor 3rd, sharp 4th, and minor 7th are sometimes played in a way that emphasizes a pitch somewhere "in the cracks" between equal-tempered pitches. Such pitches are called blue notes. Folks who are knowledgeable about microtonal tunings have speculated that these blue notes are actually approximations of the ratios 7:4 (for the minor 7th), 7:5 (for the sharp 4th), and 7:6 (for the minor 3rd). For practical purposes, I think it's easier to consider that the intent of blue notes is to escape the confines of the 12-note equal-tempered scale. When any note within the scale starts sounding a little bit predictable and "safe," leaving the scale entirely is a way of adding emotional meaning to the music.

One final note, before we leave the subject of scales: The blues scale tends to be somewhat directional. The melodic phrases in Figures 7-40, 7-42, and 7-43 all end on the lower tonic note. I haven't done a musicological analysis of blues recordings to determine the frequency with which this directionality is exhibited, but it "feels right" to me. As you experiment with the scales in this chapter you might want to keep an eye on how other musicians use them to form melodic phrases.

Quiz

1. List the Greek modes, and indicate which note is the tonic of each mode if only the white keys on the keyboard are used to play them.

2. Which Greek mode has a raised 4th step? Which modes have a lowered 2nd step?

3. If a melody contains a non-chord tone that is sustained through a chord change so that the note becomes a chord tone in the new chord, what is the non-chord tone called?

4. If a melody moves from one chord tone to another chord tone by means of a non-chord tone between the two chord tones, what is the non-chord tone called?

5. What is the pattern of whole-steps and half-steps in the ascending melodic minor scale?

6. Which minor scale contains an augmented 2nd interval?

7 What Greek mode would you use for soloing over an Fm7 chord? Your answer should be a mode whose tonic note is F.

8. How many whole-tone scales are there? How many diminished scales?

9. How many different tones are there in a pentatonic scale?

10. What is a "blue note"?

11. Which pentatonic scale would you use for soloing over a blues progression in D?

12. What note or notes most often follow the sharp 4th (flat 5th) in a blues scale when the scale is used to play a melody?

8

MORE ABOUT CHORD

PROGRESSIONS