A World Lit Only by Fire (35 page)

Read A World Lit Only by Fire Online

Authors: William Manchester

At the outbreak of the revolution most of the humanists had been ordained priests, and several, because of their eminence,

were picked by their superiors to serve as blacklisters, leading the Church’s counterrevolution. Suspecting Protestant sympathies

among his clergy, the bishop of Meaux appointed Jacques Lefèvre d’Étaples his vicar general with instructions to weed them

out. Lefèvre, then approaching seventy, was professor of philosophy at the University of Paris, the author of works on physics,

mathematics, and Aristotelian ethics, and a Latin translation of Saint Paul’s Epistles. His former pupils—the bishop was

one of them—revered him without exception.

But although he wore vestments and celebrated Mass, Lefèvre was above all a humanist. To expose medieval myths, he proposed

a clearer version of the original New Testament. He was working on a French translation of the Bible, and—like Luther —

he believed that the Gospels, not papal decrees, should be the ultimate court of theological appeal. Lefèvre was incautious

enough to observe also that he thought it “shameful” that bishops should devote their days to hunting and their nights to

drinking, gambling, and mounting

putains

—a criticism which was ill received in Meaux. Suddenly the hunter of heretics was himself condemned as one, and by the Sorbonne

at that. Fleeing Paris, he found sanctuary in Strasbourg, in Blois, and, finally, in Nérac, with Marguerite of Angoulême,

queen of Navarre and protectress of the revolution’s humanist refugees. There he resumed his scholarship and died quietly,

of natural causes, five years later.

Lefèvre was one of Marguerite’s successes. She also had her failures, notably Bonaventure Desperiers and Étienne Dolet. Both

were given her best efforts; nevertheless both died violently in Lyons. Desperiers had been guilty only of bad timing; had

he published his

Cymbalum mundi

before Luther challenged Rome, the Curia would have ignored it. Written in Latin and addressed to fellow humanists, it noted

the flagrant contradictions in the Bible, deplored the persecution of heretics, and mocked miracles. There was nothing new

here. The satires of Erasmus and the German heretics, making the same points, had been more caustic. But in the new age of

intolerance,

Cymbalum

was denounced by both sides—the Catholic witchhunters in the Sorbonne and the Protestant Calvin. Then it was publicly burned

by the official hangman of Paris. Desperiers became too hot even for Marguerite; she was forced to banish him from Nérac.

She sent him money, but the pressure was too much for him. On the run, threatened and hounded, he died, reportedly by his

own hand. Dolet, on the other hand, courted death. A printer as well as a Ciceronian scholar, he clandestinely published books

on the

Index Expurgatorius

until he was summoned before the Inquisition, found guilty, and, despite Marguerite’s attempts to intervene, burned alive.

Some humanists were victims; some became leaders of the revolt. All, when captured, met hideous deaths. Those who had led

became martyrs, but the deaths of leaders and led seem equally senseless. In his

Christianismi restitutio

(

The Restitution of Christianity

) the Spanish-born theologian and physician Michael Servetus dismissed predestination as blasphemy; God, he wrote, condemns

only those who condemn themselves. Servetus was naive enough to send a copy to a preacher who believed in predestination as

the revealed word and who, knowing which church Servetus would attend and when, had him ambushed at prayer. A Protestant council

sentenced him to death by slow fire. Now terrified, aware of his blunder, the condemned author begged for mercy—not for

his life; he knew better than that; he merely wanted to be beheaded. He was denied it. Instead he was burned alive. It took

him half an hour to die.

The Catholics who quartered the body of the Swiss Huldrych Zwingli and burned it on a pyre of dried exrement were equally

merciless; so was Martin Luther, who had regarded Zwingli as a rival and called his ghastly death “a triumph for us.” In the

darkness enveloping Christendom no one recalled that as a young priest the slain Swiss had taught himself Greek to read the

New Testament in the original and possessed a profound knowledge of Tacitus, Pliny, Homer, Plutarch, Livy, Cicero, and Caesar.

All they remembered was that he had said he would prefer “the eternal lot of a Socrates or a Seneca than of a pope.”

Perhaps the most poignant figure in the strife—and certainly one of the most tragic—was Ulrich von Hutten. Once he had

distinguished himself as a humanist, a Franconian knight, a brilliant satirist, and one of the first scholars in central Europe

to cherish the vision of a unified Germany. Like Luther, he had abandoned Latin to help shape the German language as it is

spoken today; his

Gesprächbüchlein

, published the year after Worms, was a greater contribution to linguistics than to theology. But Hutten was one of the committed

humanists, and like most Reformation zealots he displayed more enthusiasm than judgment. Unwisely, he had cast his lot with

Von Sickingen, whose defeat transformed him into a penniless fugitive robbing farms for food as he fled toward Switzerland.

Reaching it, he headed straight for Basel, and Erasmus. He expected his fellow humanist to support him, but that was asking

too much. Not only had his vehement rhetoric offended the man who preached moderation and tolerance; Hutten had denounced

Erasmus as craven for not supporting Luther. Now, in Basel, the victim of his abuse refused to receive him, wryly explaining

that his stove provided too little heat to warm the German’s bones.

Angry, desperate, and ill—his affliction was venereal—Hutten abandoned both dignity and decency by turning to extortion.

He wrote a scurrilous pamphlet about Erasmus (

Expostulation

) and offered to suppress it in exchange for money. Erasmus indignantly refused. Then Hutten began circulating it privately.

The local clergy asked Basel’s city fathers to expel the polemicist, and it was done. Hutten moved to Mulhouse and sent his

manuscript to the press. A mob drove him out. In the summer of 1523 he stumbled into Zurich, only to find that there, too,

the city council was preparing a motion of expulsion. Homeless, broke, banished from society, he retreated to an island in

the Lake of Zurich, and there, aged thirty-five, he succumbed to syphilis. His sole possession was his pen. Valuable only

a year earlier, it was now worthless.

A

LL

P

ROTESTANT

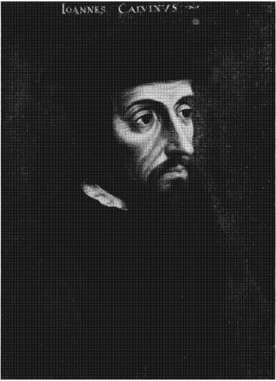

regimes were stiffly doctrinal to a degree unknown—until now—in Rome. John Calvin’s Geneva, however, represented the

ultimate in repression. The city-state of Genève, which became known as the Protestant Rome, was also, in effect, a police

state, ruled by a Consistory of five pastors and twelve lay elders, with the bloodless figure of the dictator looming over

all. In physique, temperament, and conviction, Calvin (1509–1564) was the inverted image of the freewheeling, permissive,

high-living popes whose excesses had led to Lutheran apostasy. Frail, thin, short, and lightly bearded, with ruthless, penetrating

eyes, he was humorless and short-tempered. The slightest criticism enraged him. Those who questioned his theology he called

“pigs,” “asses,” “riffraff,” “dogs,” “idiots,” and “stinking beasts.” One morning he found a poster on his pulpit accusing

him of “Gross Hypocrisy.” A suspect was arrested. No evidence was produced, but he was tortured day and night for a month

till he confessed. Screaming with pain, he was lashed to a wooden stake. Penultimately, his feet were nailed to the wood;

ultimately he was decapitated.

Calvin’s justification for this excessive rebuke reveals the mindset of all Reformation inquisitors, Protestant and Catholic

alike: “When the papists are so harsh and violent in defense of their superstitions,” he asked, “are not Christ’s magistrates

shamed to show themselves less ardent in defense of the sure truth?” Clearly, he would have condemned the Jesus of Matthew

(5:39, 44) as a heretic.

*

In Calvin’s Orwellian theocracy, established in 1542, acts of God—earthquakes, lightning, flooding—were acts of Satan.

(Luther, of course, agreed.) Copernicus was branded a fraud, attendance at church and sermons was compulsory, and Calvin himself

preached at great length three or four times a week. Refusal to take the Eucharist was a crime. The Consistory, which made

no distinction between religion and morality, could summon anyone for questioning, investigate any charge of backsliding,

and entered homes periodically to be sure no one was cheating Calvin’s God. Legislation specified the number of dishes to be served at each meal and the color of garments worn. What one was permitted

to wear depended upon who one was, for never was a society more class-ridden. Believing that every child of God had been foreordained,

Calvin was determined that each know his place; statutes specified the quality of dress and the activities allowed in each

class.

But even the elite—the clergy, of course—were allowed few diversions. Calvinists worked hard because there wasn’t much

else they were permitted to do. “Feasting” was proscribed; so were dancing, singing, pictures, statues, relics, church bells,

organs, altar candles; “indecent or irreligious” songs, staging or attending theatrical plays; wearing rouge, jewelry, lace,

or “immodest” dress; speaking disrespectfully of your betters; extravagant entertainment; swearing, gambling, playing cards,

hunting, drunkenness; naming children after anyone but figures in the Old Testament; reading “immoral or irreligious” books;

and sexual intercourse, except between partners of different genders who were married to one another.

To show that Calvinists were merciful, first offenders were let off with reprimands and two-time losers with fines. After

that, those who flouted the law were in real trouble. The Consistory made no allowances for probation, suspended sentences,

or rehabilitation programs, and Calvin assumed that everyone enjoyed community service without being sentenced to it. Excommunication

and banishment from the community were considered dire, though those living in a more permissive age might find them less

appalling. In any event, there were plenty of other penalties, some of them as odd as the offenses they punished. A father

who stubbornly insisted upon calling his newborn son Claude spent four days in the canton jail; so did a woman convicted of

wearing her hair at an “immoral” height. A child who struck his parents was summarily beheaded. Abortion was not a political

issue because any single woman discovered with child was drowned. (So, if he could be identified, was her impregnator.) Violating

the seventh commandment was also a capital offense. Calvin’s stepson was found in bed with another woman; his daughter-in-law,

behind a haystack with another man. All four miscreants were executed.

Of course, it proved impossible to legislate virtue. Some of Calvin’s devoted followers insisted that it was possible, that

the Consistory’s moral straitjacket worked; Bernardino Ochino, an ex-Catholic who had found asylum in the city-state, wrote

that “Unchastity, adultery, and impure living, such as prevail in many places where I have lived, are here unknown.” In fact

they were widely known there; the proof lies in the council’s records. A remarkable number of unmarried young woman who worshiped

with Ochino managed to carry their pregnancies to term unde-

John Calvin (1509–1564)

tected. Some abandoned their issue on church steps or alongside forest trails; some named their male co-conspirator, who then

married them at sword’s point; some lived as single parents, for not even Calvinists could orphan an innocent infant.

On other issues they were adamant, however. The ultimate crime, of course, was heresy. It was even blacker than witchcraft,

though sorcerers could not be expected to appreciate the distinction; after a devastating outbreak of plague, fourteen Geneva

women, found guilty of persuading Satan to afflict the community, were burned alive. But because the soul was more precious

than the flesh, the life expectancy of the apostate was even shorter. Anyone whose church attendance became infrequent was

destined for the stake. Holding religious beliefs at odds with those of the majority was no excuse in Geneva or, for that

matter, in other Protestant theocracies. It was a consummate irony of the Reformation that the movement against Rome, which

had begun with an affirmation of individual judgment, now repudiated it entirely. Apostasy was regarded as an offense to God

and treason to the state. As such it was punished with swift, agonizing death. One historian wrote, “Catholicism, which had

preached this view of heresy, became heresy in its turn.”