A World Lit Only by Fire (37 page)

Read A World Lit Only by Fire Online

Authors: William Manchester

B

UT MOST MEMBERS

of the Catholic hierarchy saw it differently. Now, they believed, they had seen the faces of the Protestant heresy—the

fact that half the looting troops had been Spanish Catholics was ignored—and now they would move with just as much vigor,

intolerance, and brutality as those rebelling against their God. Sir Isaac Newton would not discover his Third Law until a

generation later, but it was already in effect: henceforth every action by the insurgent Christians would provoke an equal

and opposite reaction in Rome. And the Church’s reflexive responses to dissent matched those of the schismatics. The same

doom, in the same guise, awaited those who had betrayed Rome: torture, drawing and quartering, the noose, the ax, and, most

often, the stake. In that age the world was still lit only by fire. At times it seemed that the true saints of Christianity,

Protestant and Catholic alike, had become blackened martyrs enveloped in flames.

In vain enlightened Catholics urged internal disciplinary reforms, curing the blight which had driven good Christians from

their ancestors’ faith—the corruption of the clergy, the luxurious lives led by prelates, the absence of bishops from their

dioceses, and nepotism in the Holy See. At the very least, they argued, pontiffs should rededicate themselves to devotional

lives, good works, and the reaffirmation of beliefs under attack by Protestants: for example, the real presence of Christ

in the Eucharist, the divinity of the Madonna, the sanctity of Peter.

Instead the Vatican committed its prestige to reaction, repression, and military and political action against rulers who had

left the Church. As always, when scapegoating has become public policy, the Jews were blamed. In Rome they were confined to

a ghetto and forced to wear the Star of David. Meantime, Catholic princes were persuaded to make war in the name of the savior,

or

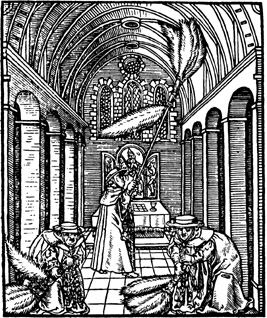

Lutheran satire on papal reform

even to send hired assassins into the courts and castles of the Protestant nobility. Every aspect of Protestantism—justification

by faith alone, exaltation of the Lord’s Supper, the propriety of clerical marriage—was condemned in a stream of bulls.

Nevertheless the rebel faiths continued to prosper. In 1530 Charles V, at the insistence of the Curia, signed a decree directing

the Imperial Chamber of Justice (Reichskammergericht) to take legal action against princes who had appropriated ecclesiastical

property. They were given six months’ grace to comply. None did.

The Spanish Inquisition is notorious, but the Roman Inquisition, reinstituted in 1542 as a pontifical response to the Reformation,

became an even crueler reign of terror. All deviation from the Catholic faith was rigorously suppressed by its governing commission

of six cardinals, with intellectuals marked for close scrutiny. As a consequence, the advocates of reform, who had proposed

the only measures which might have healed the split in Christendom, fell under the dark shadow of the hereticators’ suspicion.

No Catholic was too powerful to elude their judgment. The progressive minister of Naples, disgusted with the venal Neapolitan

church court, began trying indicted ecclesiastics in the city’s civil court. For thus violating the

privilegium fori

, he was summarily excommunicated. The liberal Giovanni Cardinal Morone was imprisoned on trumped-up charges of unorthodoxy.

Another cardinal, who had actually reconverted lapsed Catholics, ran afoul of the Vatican by attempting to prevent war between

the Habsburgs and France. He was recalled to Rome, accused of heresy, and ruined. The archbishop of Toledo, because he had

openly expressed admiration of Erasmus, was sentenced to seventeen years in a dungeon, and after the death of Clement VII

another Erasmian—Pietro Carnesecchi, who had been the pope’s secretary—was cremated in a Roman auto-da-fé.

In the opinion of the Apostolic See, most Catholic rulers, including the Holy Roman emperor, were far too tolerant of heresy.

Francis I was particularly disappointing, and the Vatican was delighted when, after his death at Fontainebleau in 1547, he

was succeeded by the devout and murderous Henry II, at whose side lay the even more homicidal Diane de Poitiers, royal mistress

and enthusiastic

Inquisiteuse

. Together they planned a grand strategy to crush all French apostates. The printing, sale, or even the possession of Protestant

literature was a felony; advocacy of heretical ideas was a capital offense; and informers were encouraged by assigning them,

after convictions, one-third of the condemneds’ goods. Trials were conducted by a special commission, whose court came to

be known as

le chambre ardente

, the burning room. In less than three years the commission sentenced sixty Frenchmen to the stake. Anne du Bourg, a university

rector and a member of the Paris Parlement, suggested that executions be postponed until the Council of Trent defined Catholic

orthodoxy. Henry had him arrested. He meant to see him burn, too, but destiny—the Protestants naturally said it was God

—intervened. The king was killed in a tournament in 1559. His queen, his mistress, and the Vicar of Christ mourned him. Du

Bourg, of course, did not, though he went to his death anyway as a

martyr luthérien

.

H

ENRY

II

OF

France had been admired, applauded, and blessed in St. Peter’s, but in the twelve years following the rise of Luther the

sovereign most cherished in Rome was Henry VIII of England. Henry seemed, indeed, the answer to a Holy Father’s prayers. The

fact that his handsome features, golden beard, and athletic build also made him the answer to maidenly and unmaidenly prayers

appeared to be irrelevant; the Apostolic See was in no position to condemn royal lechery. More important, before the death

of his elder brother made him heir to his father’s throne, he had been trained to be a priest.

By the time he mounted the throne, in 1509, he could and did quote Scripture to any purpose, and after the monk of Wittenberg

had posted his Ninety-five Theses on the Castle Church door, Henry had denounced him in his

Assertio septem sacramentorum contra M. Lutherum

, a vigorous defense of the Catholic sacraments, probably ghostwritten by Richard Pace, Bishop John Fisher of Rochester, or,

possibly, Erasmus. In it he asked, “What serpent so venomous as he who calls the pope’s authority tyrannous?” and declared

that no punishment could be too vile for anyone who “will not obey the Chief Priest and Supreme Judge on earth … Christ’s

only vicar, the pope of Rome.”

Luther, replying with his typical grace, referred to his critic as that “lubberly ass,” that “frantic madman … that King of

Lies, King Heinz, by God’s disgrace King of England,” and continued: “Since with malice aforethought that damnable and rotten

worm has lied against my King in heaven, it is right for me to bespatter this English monarch with his own filth.” He then

sponsored a Protestant conspiracy in the heart of London, the Association of Christian Brothers. The association circulated

anti-Catholic tracts and reached its climax the year before Rome’s sack with the publication of William Tyndale’s famous —

infamous in the Vatican—English translation of the New Testament, which made the thirty-four-year-old British clergyman

an archenemy, not only of the Apostolic See, but also of his then-Catholic sovereign.

Tyndale was a humanist, and his tale is an example of the deepening hostility between men of God and men of learning. English

humanists had rejoiced at Henry’s coronation. Lord Mountjoy had written Erasmus of the “affection [the king] bears to the

learned.” Sir Thomas More said of the new monarch that he had “more learning than any English monarch ever possessed before

him,” and asked, “What may we not expect from a king who has been nourished by philosophy and the nine muses?” Henry’s invitation

to Erasmus, urging him to leave Rome and settle in England, appeared to confirm the enthusiasm of English scholars. It seemed

inconceivable that the popular monarch, faced with a choice between faith and reason, should choose faith.

But Erasmus, after accepting the invitation, found that the king had no time for him. And as the religious revolution grew

in ferocity, Henry’s commitment to Catholicism deepened. Lord Chancellor More, with royal encouragement, imprisoned the Christian

Brothers and other heretics. And the Tyndale affair, which appalled English intellectuals, seemed to align him with the most

reactionary heresimachs.

William Tyndale had conceived his translation while reading ancient languages at Oxford and Cambridge, and he had begun work

upon it shortly after his ordination as a priest in 1521, the year of Luther’s condemnation at Worms. A Catholic friend reproached

him: “It would be better to be without God’s law than the pope’s.” Tyndale replied: “If God spare me, ere many years I will

cause the boy that driveth the plough to know more of the Scripture than you do.”

Had he valued his own years on earth, he would have heeded his friend. It was one thing for Erasmus to publish parallel texts

of the Gospels in Latin and Greek; few, after all, could read them. This was another matter altogether. It was actually dangerous;

the Church didn’t want—didn’t permit—wide readership of the New Testament. Studying it was a privilege they had reserved

for the hierarchy, which could then interpret passages to support the sophistry, and often the secular politics, of the Holy

See.

Tyndale had been warned that finding a printer for his completed manuscript would be difficult. Luckless in England, he crossed

the Channel and found a publisher in Catholic Cologne. The text had been set and was on the stone when a local dean heard

of it, grasped the implications, and persuaded authorities in Cologne to pi the type. Fleeing with his manuscript, Tyndale

found that he was now a police figure; had post offices existed, his picture would have been posted in them. The Frankfurt

dean sent word of his criminal attempt to Cardinal Wolsey and King Henry, who declared Tyndale a felon. Sentries were posted

at all English ports, under orders to seize him upon his return home.

But the fugitive was less interested in his personal freedom than in seeing his work in print. He therefore journeyed to Protestant

Worms, where, in 1525, Peter Schöffer published an octavo edition of his work. Six thousand copies had been shipped to England

when Tyndale was again spotted. He was on the run for the next four years. Then, believing himself safe, he settled in Antwerp.

However, he had underestimated the gravity of his offense and the persistence of his sovereign. British agents had never ceased

stalking him. Now they arrested him. At Henry’s insistence he was imprisoned for sixteen months in the castle of Vilvorde,

near Brussels, tried for heresy, and, after his conviction, publicly garrotted. His corpse was burned at the stake, an admonition

for any who might have been tempted by his folly.

The royal warning was unheeded. You can’t kill a good book, including the Good Book, and Tyndale’s translation was excellent;

later it became the basis for the King James version. Despite a lengthy

Dialogue

by More, denouncing the translation as flawed, copies of the Worms edition had been smuggled into the country and were being

passed from hand to hand. To the bishop of London this was an intolerable, metastasizing heresy. He bought up all that were

for sale and publicly burned them at St. Paul’s Cross. But the archbishop of Canterbury was dissatisfied; his spies told him

that many remained in private hands. Protestant peers with country houses were loaning them out, like public libraries. Assembling

his bishops, the archbishop declared that tracking them down was essential—each was placing souls in jeopardy—and so,

on his instructions, dioceses organized posses, searching the homes of known literates, and offered rewards to informers —

sending out the alarm to keep Christ’s revealed word from those who worshiped him.