Against Death and Time: One Fatal Season in Racing's Glory Years (18 page)

Read Against Death and Time: One Fatal Season in Racing's Glory Years Online

Authors: Brock Yates

THE DAY AFTER THE RACE DAWNED SUNNY AND

calm. The storm had passed. I ate breakfast with Eldon, who once

again rattled on about the crashes in his backyard, as if to exorcise the

demons that haunted the track beyond his juniper tree. Trying to salvage something for a story so that my whole trip wouldn't be wasted,

I walked back to Gasoline Alley. It was deserted, save for the crews

loading up the battered, grease-and-rubber-stained cars that had survived the race. They would head to Milwaukee, where next weekend

it would all start again.

The Vukovich garage was still closed, no doubt housing the

charred hulk of the Hopkins. I wondered what would be done with

such a wreck, having been the vessel of death for such a man as Bill

Vukovich. I later learned that the car was repaired, repainted, and

revived to carry young Jim Rathmann to the second starting position the next year before falling out with engine trouble. The old warrior

would appear twice more at the Speedway, its role in the horrific incident on the backstretch three years earlier long forgotten-or purposely ignored.

As I'd expected, the primary subject among the men in Gasoline

Alley was the Vukovich crash. It had apparently begun when Rodger

Ward, driving the old Kuzma dirt-track car, caught a gust of wind

while exiting the second turn. Before he could regain control, the car

slapped the wall and tumbled in front of Al Keller, in his even older

Kurtis, which was equipped with only a hand-brake hung on the outside of the cockpit. Keller apparently yanked too hard and locked up

the wheels, sending his car into a slide in front of Johnny Boyd, a racing buddy of Vukovich's from Fresno. Boyd hit the spinning Keller as

Vukovich-running perhaps 100 mph faster than all three-blazed

off the turn and into the melee. With nowhere to go, he clipped

Boyd's rear wheel, sending both cars tumbling. Vukovich's Hopkins

slammed against the base of the footbridge crossing the track and

sailed upside down over the retaining wall, landing on a security

patrol Jeep. It then flipped crazily to end upside down, on fire.

As Boyd's car tumbled down the track, he ducked deep into the

cockpit-which saved him, other than some badly scuffed knuckles.

In the middle of the madness, with his car bouncing like a berserk

beach ball, he later recalled seeing his wristwatch coming loose in the

impact. "Oh shit, I'm gonna lose my watch," he thought to himself.

The car slid to a stop upside down, with Boyd trapped inside. He

heard a voice yell, "Oh no, he's really had it!"

"Bullshit," yelled Boyd from inside the wreck. "Get this son-ofa-bitch off me!"

Two men helped him escape. Once clear of the wreck, he spotted

Keller, one of his rescuers, but also, perhaps, partly of the cause. In a

fit of rage, Boyd grabbed him and began cursing and pounding him

on the chest. At that point Ward came up and grabbed them both. "Get off the track, you idiots, before some other dummy comes

through here and gets all of us."

The dazed, confused trio staggered into the infield as another race

car slid to a halt. Out jumped Ed Elisian, a Northern Californian from

an Armenian family whose admiration for Vukovich bordered on

hero worship. Hysterical, he tried to cross the track until he was subdued by guards. Elisian was trying to reach the smoking wreck of his

fallen idol, a futile and irrational act that, ironically, would win him a

sportsmanship award following the race.

It was later determined that Vukovich had died from a basal fracture

of the skull, probably suffered in the first millisecond of the first flip.

The gruesome photos carried the following day in newspapers around

the world-of the burning car with Vukovich's gloved hand probing

out of the bodywork-added a ghoulish touch to the accident.

Old-timers at the Speedway talked endlessly about the coincidence of the 1939 crash, at the same spot, that had killed Floyd

Roberts. Like Vukovich, Roberts had won the previous year. When

exiting the second turn on the 107th lap, he had run into the spinning

car of Bob Swanson and also crashed over the outside fence to die of

a broken neck.

Anger over who had caused the crash surged through Gasoline

Alley like an evil wind. Much of the blame was directed at Ward,

whose profligate lifestyle left him, in the minds of many, too physically debilitated to run the full distance without losing concentration.

Whether or not this was the case, Ward was to use the incident to

transform his life. Soon after, Ward married a staunch Baptist

woman, stopped drinking and gambling, and would go on to win two

500-mile races and become a stellar spokesman for the sport. Others,

like Boyd, laid the blame on Keller, a rookie in an ancient car who

panicked and locked up his brakes. This in turn had left Boyd no

room to maneuver, and blocked the way for the surging Vukovich.

But while an automobile is traveling almost three miles a minute, decisions at close quarters are often beyond human capability. In the

end, the crash was laid off on "racing luck," the catch-all repository

for all such disasters, when the victim is in the wrong place at the

wrong time.

While Sweikert was headed for his Indianapolis victory, the pain

and misery had not ended. As the final laps unfolded, Cal Niday, a

thirty-nine-year-old midget racing champion who had already lost

a leg in a motorcycle crash, was riding in fourth place in his locally

owned D.A. Lubricants Kurtis roadster when he lost control in the

fourth turn. The car slammed the wall, then caromed across the

track into an infield ditch. He was hauled off to the infield hospital, where chief doctor C. B. Bonner discovered a frontal skull fracture, a crushed chest, and third-degree burns on his right leg.

Niday was taken to Methodist Hospital, where he started to

recover. Nine days later, he suffered a hemorrhage of his pleural

cavity, a collapse of his right lung, paralysis of his bowels, and severe

jaundice possibly caused by a bad blood transfusion or a ruptured

liver. A team of surgeons opened Niday's chest cavity to make repairs

and miraculously, he survived. But like his cohorts, he could not stay

away from fast cars. In his seventies, he was killed running in a race

for vintage midgets in California.

The nightmare of the 500 behind me, I drove back to Los Angeles

in three hard days. Still hoping to salvage a story on Vukovich, I

headed north to Fresno for his funeral. It was huge. Perhaps three

thousand mourners appeared as the Mad Russian was laid to rest.

The Fresno Junior Chamber of Commerce announced the establishment of a scholarship fund in the Manual Arts Department of Fresno

State College, a fitting memorial to a man who lived and died with

machinery of the highest form.

A week later, in Milwaukee, a young charger from Massachusetts

named Johnny Thomson won the 100-miler on the ancient oval, beating Sweikert in a close race. A new generation of drivers were ready to take the place of the dead king. Thomson was driving for Peter Schmidt,

who only two weeks before had lost his driver, Manny Ayulo. But in

the sport of AAA championship racing in the mid-1950s, fourteen

days was ancient history.

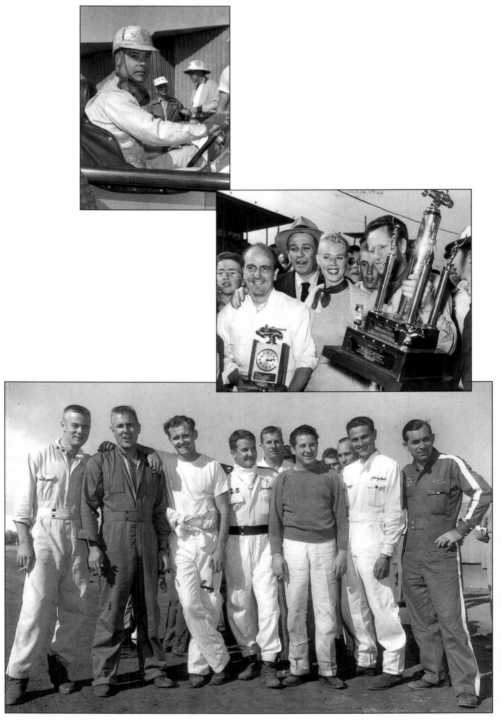

The Mad Russian ready for war. Bill Vukovich

prepares for a 100-mile championship race

protected only by a thin leather helmet, goggles,

and a pair of driving gloves. Note the absence

of a roll-bar or protective cage or insulation

from the red-hot exhaust pipe within a few

inches of his right elbow.

0

G

.V

7

0

P.

C

v

3

x

0

Two racing pals Manuel Ayulo (I) and

Jack McGrath (r) share a victorious moment

following the 1953 Milwaukee, Wisconsin

100-mile championship race. Both men grew

up in Los Angeles and raced midgets and

hot rods together before gaining success in

the major leagues of AAA competition.

Sadly, both men would die in the

brutal 1955 season.

Brave men at play. Sacramento, CA 1954 prior to a AAA 100-mile race. Left to right: Jerry Hoyt, Jimmy Bryan

(with his omnipresent cigar), Bob Sweikert, Jimmy Reece, Rodger Ward, Johnny Boyd, and Edgar Elder.

Standing behind Reece and Ward is Sam Hanks. The four men on the left would all die in racing accidents

within six years. Bryan, Sweikert, and Hanks would be future Indianapolis 500 winners. Ward would win the

big race twice. (Dick Wallen Productions)

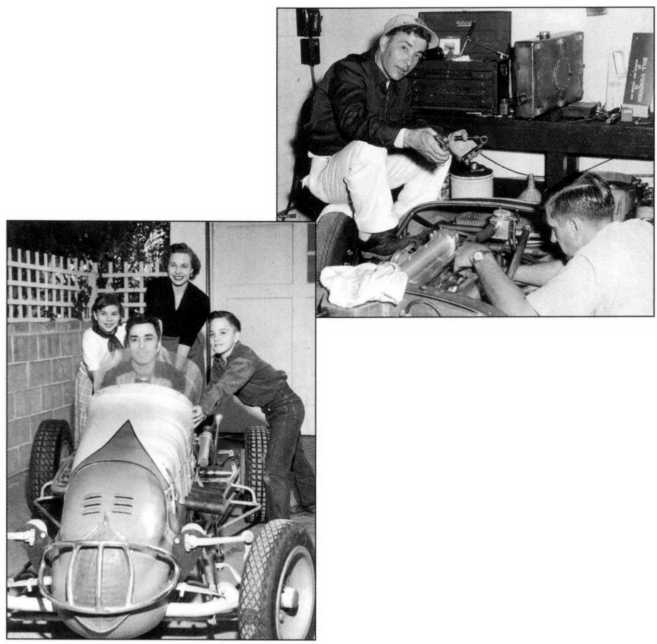

Bill Vukovich works to build hand

strength prior to the 1955 Indianapolis

500. Crewman Frank Coon works on the

Hopkins Special's Meyer-Drake engine.

Bill Vukovich poses for a publicity shot at

his Fresno home with his wife Esther and

children Billy, Jr., and daughter Marlene.

Billy, Jr. would go on to compete at

Indianapolis from 1968-83 finishing

2nd in 1973 and 3rd in 1974. Vukovich's

grandson, Billy III, ran at Indianapolis

from 1988-1990.

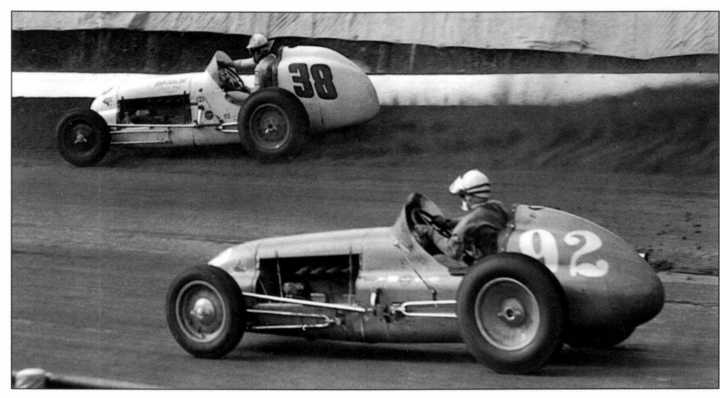

War at 120 miles an hour. Don Freeland (number 38 M.A. Walker Special) and Rodger Ward battle for position

during the 1953 Milwaukee 100-mile championship race. Both men battle for control on the rutted, slippery dirt

surface, struggling with their heavy machines without power steering or protection from the flying stones and

dirt. Freeland is "rim-riding" against the outer rail, seeking better traction on the cushion of dirt flung outward

by the spinning tires. The races were flat out, with no pit stops or relief, forcing the drivers to near exhaustion.

Ward can be seen wearing a plastic visor and two pairs of goggles to help keep his vision clear. Note the absence

of any rollover protection. The drivers sat in front of seventy gallons of volatile methanol fuel carried in easily

punctured fuel tanks. (Dick Wallen Productions)