Against Death and Time: One Fatal Season in Racing's Glory Years (21 page)

Read Against Death and Time: One Fatal Season in Racing's Glory Years Online

Authors: Brock Yates

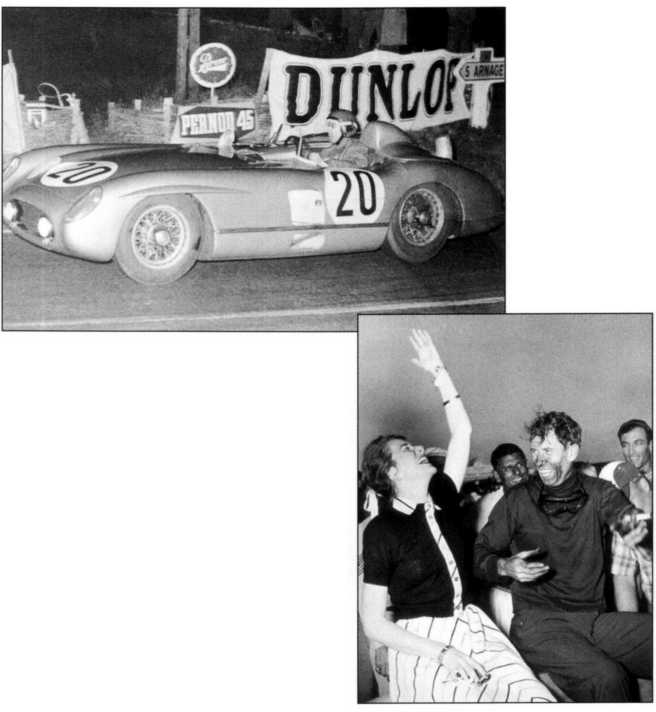

Pierre Levegh at the wheel of

the ill-fated 300SLR

Mercedes-Benz prior to his

death at LeMans. The

impact of the accident sent

the engine and Front suspension assembly into the

crowd while Levegh, wearing

no seat belt, as was the practice in those days, was

pitched from the cockpit

and killed.

John Fitch celebrates a 1953 victory while driving for

the Cunningham sports car team. With him is his

wife, Elizabeth. During the 1955 LeMans race she

stayed in Switzerland and heard a report on

U.S. Armed Forces radio that it was her husband,

not his co-driver Pierre Levegh, who had been

involved in the catastrophic crash.

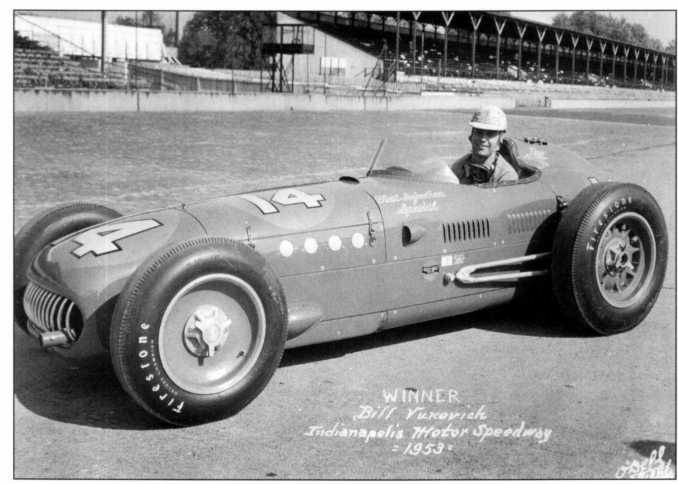

Bill Vukovich in the revolutionary Kurtis-Kraft 500A fuel-injection special that carried him to

victory at Indianapolis in 1953 and 1954 with a near miss in 1952.

Who in God's name were these people, who dealt with death so

casually? Were they all insane? All obsessed with a death wish?

"Motorized Lemmings?"-as Newsweek columnist John Lardner

denounced them following the Vukovich crash. Surely some of them

had come home from the war restless for action, bored with the Ike

and Mamie good life that had overwhelmed the prosperous, vinyl- and

dacron-coated nation with its Barcaloungers, its drip-dry fashions, its

automatic everything, and its nightly dose of network feel-good.

Others, like Jack Kerouac and his fellow beatniks, were rebelling in the

coffeehouses of Greenwich Village and Haight-Ashbury, while some,

wilder and more lethal, were forming motorcycle gangs like the Hells

Angels, Booze-Fighters, Satan's Sinners, and Outlaws.

An Englishman once observed that at some point, all sane young

men in their late teens or early twenties will attempt to kill themselves

in a looney, risk-taking adventure. The poet Richard Hugo, who,

before being cursed with alcohol and depression, was a pilot in World

War II, confirmed the suspicion. Following V-E day, his squadron was

stationed in Sicily, training for future combat. Their aircraft, P-47

fighters with giant radial engines, were claimed to be unditchable in

water. Flight engineers warned all the pilots that landing in water

meant certain death. In the summer of 1945 a fellow pilot and friend

of Hugo's was returning from a training flight over the Bay of Naples

when, on a whim, he decided to try a water landing with the gear up.

He was killed instantly. Hugo would later ponder the possibility that

deep in the psyche of all young men lies a hatred of peace and safety

and an irresistable urge to flout all rules and conventions. He suggested that his friend might have chosen the risk as opposed to the

prospect of returning home to the cushy domesticity of postwar America. His choice was to play Russian roulette with his airplane

and his own mortality in the cauldron of war.

Years later, Michael Cimino would have one of the characters in his

classic film The Deer Hunter play the same game with his own .45

automatic, when there was no gambling involved. This urge to walk

the edge seemed particularly tied to war, whereas conventional thinking presumed that human nature would be to seek to preserve one's

life rather than waste it. Yet following the American Civil War, young

men rushed west to face the dangers of savage Indians, cattle stampedes, rustlers, fierce weather, and drunken gunfighters rather than

languish in the tranquility of the East. So too for the World War I vets

who migrated to Paris as the Lost Generation, there to booze and barfight themselves insensate. Looked at in this light, the men who

unleashed their passions in race cars and on motorcycles in the late

1940s and the 1950s were hardly breaking new ground in terms of

mad, self-absorbed risks to life and limb.

Ironically, the technology that rose out of the industrial creativity

energized by the war effort on all sides offered even more macabre

opportunity for self-imposed danger. The cars competing at places

like Indianapolis and in European road racing were light years more

advanced than those of the prewar years, thanks to quantum leaps in

metallurgy, fuels, bearing surfaces, lightweight alloys, and synthetic

materials of all kinds. But regardless of the fevered increases in performance, the men riding inside those incredible capsules remained

as fragile and physically vulnerable as ever.

Bill Vukovich's death caused a short, frantic outcry in the national

press and among a few politicians who denounced the sport of automobile racing as barbaric madness appealing to only the basest, most

ghoulish human instincts. Several bills to ban racing totally were

introduced in Congress, but were ignored. Homer Capehart, the

powerful Republican senator from Indiana, was sure to roadblock

any such legislation, which meant certain death in the Upper House.

The danger and carnage at Indianapolis seemed to trace a course

in American society that ran in direct opposition to the pallid, pastelhued lifestyle now recalled from the 1950s. In the midst of the saccharine sweetness that engulfed daily living and that enraged

Kerouac and his ilk, automobile racing stood as a steaming fissure of

violence and death on an otherwise tranquil landscape.

Of the thirty-three men who climbed into race cars at the start of

the 1955 Indianapolis 500, eighteen of them would die violent deaths

in races-three of them before the year was ended. All of the top five

finishers were doomed, as were Keller, Elisian, and McGrath, while

two others would suffer horrific injuries that would end their careers.

Half a century later, when two major wars were fought in Iraq and

American casualties barely reached the triple digits, the notion of a

sporting activity that consumed the lives of over half its participants

borders on the demented. Such levels of danger would simply not be

tolerated today. Life has become too precious and too easily preserved

to accept the idea that death and injury are realistic components of

war, much less of a sport. Lawmakers, insurance underwriters, social

activists, safety groups, editorialists, and moralists of all stripes would

be at full cry at the first hint of such potential carnage. Risk-taking,

once an accepted component of life, has in the past few decades been

relegated to the closet with other antisocial activities, leaving the men

who knowingly faced destruction in 1955 among the more bizarre

and perverted of humankind.

Returning to Los Angeles, I received word, as expected, from the

editors of the Saturday Evening Post that my story had been cancelled.

I was settling back into my little apartment to devise another project

when I received a call from a friend who edited a small, struggling

sports car magazine based in New York titled Sports Cars Illustrated.

His European correspondent had met a lovely girl while on vacation in

Monte Carlo and, being a wealthy Italian who didn't need the work, had

quit on the spot. The editor needed someone to cover the upcoming Le Mans 24-Hour race in France in less than two weeks. If I was available, a free plane ticket, modest expenses, and $500 would be mine.

Having no real prospects for work and figuring a week or two in Paris

and environs might be good for the soul, I jumped at the offer.

As I readied myself for the trip to France, updating my passport,

packing, and arranging airline reservations, I couldn't resist making

one more trip to Travers and Coon's shop to fathom their reaction to

Vuke's death. Jim Travers was alone when I arrived early one morning. The Keck streamliner was in its customary spot on jack-stands in

the middle of the shop floor, surrounded by spare parts. Travers was

seated at his small desk, littered as always with blueprints, work

orders, and invoices. "Look at this," he said, a hint of bitterness in his

voice. He handed me a sheet of paper from the Speedway listing the

finishing order and the prize money. Vukovich was placed twentyfifth, with winnings of $10,833.64, a total inflated by the bonus money

he received for leading so many laps before crashing. "At least he's

ahead of McGrath. They've got him listed twenty-sixth. I hope Vuke

understood that the nitro shit jack was using didn't work. That ain't

much solace, but at least it's something."

Travers reached into the pile on his desk and pulled out an

eight-by-ten photo. It was a shot taken from behind the second

turn facing down the long back straight. Ward's car could be seen

scuffing the wall in a cloud of dust, with Keller and Boyd close

behind. In the foreground, headed into the chaos that was about to

commence, was Vukovich. "Take a close look at that," said Travers,

handing me the picture.

I examined it closely, then handed it back. "It looks like what

everybody described, basically," I shrugged.

"Except for one thing. Look closely at Vuke's head. It's tilted downward. I think he was reaching into his lap, looking for the cloth he

always carried to wipe his goggles. In the second he took his eyes off the track, that may have been enough for him to get into Boyd.

Maybe, just maybe, if he'd had that extra second, he might have

missed the whole thing."

"That close, huh?" I asked.

"That close. That much difference. Right at that point on the track

he's hard on the throttle, coming off the corner at maybe 140, 150.

One second makes a world of difference at that speed."