All That Is Bitter and Sweet (42 page)

There were more lessons to be learned that week, effective ways to improve communication and approach one another directly about hurt feelings or disagreements without causing harm. But after that sculpt, everything seemed anticlimactic. I found myself increasingly identifying with the other clients at Shades during our group interactions, and I picked out a couple I particularly liked to sit next to at meetings. Meanwhile, physical symptoms resumed and became more alarming, waves of dizziness and sensations that made me feel as if an electric wire were being touched to my body. Episodes of near hyperventilation and almost passing out increased, apparently in reaction to the painful childhood memories being dredged up and daylighted in group sessions and exacerbated by seeing my parents in the same room, at the same time, and by the idea of my sister finally having her long deserved moment of being heard and validated. All this triggered the first layers of years and years of my own pent-up feelings. They were roiling right under the surface of my skin, quivering in my lungs, coming out any way they could. It was becoming clear to me that all the stuff I had been trying to manage with the same ole same ole coping behaviors could no longer be contained. I was like a papier-mâché sculpture, trying desperately to patch my peeling layers, while something about being in this place spoke to a part of me that was so ready to stop the patching. My emotions were beckoning me to relax in the nascent knowledge that it was okay to come unpeeled, something my conscious brain was not quite ready to believe.

On Thursday night, Shades invites the whole community to an open all-addictions Twelve Step meeting for friends and family of the clients as well as any former clients. Apparently, folks drive for hours every Thursday to reconnect with what has become hallowed ground, the place where they found their recovery. I had no idea what it was all about, but I was curious, open-minded, and hopeful it would have something valuable for me. As I was dressing in my room, my mind started to drift back to what the next week at home held in store for me. I heard a voice from deep inside of me say,

I don’t want to leave

. It was so clear and so startling that I froze. It wasn’t an idea or a thought—it was a voice coming not from my head, but from deep inside my chest. I sat on the edge of my bed and thought,

Would there ever be a place for me in a place like this?

All the questionnaires I had filled out on Monday didn’t seem to apply. I didn’t have an eating disorder. I wasn’t a drug addict. I didn’t have a gambling problem, a shopping problem … When I introduced myself at the beginning of each group, I said I was codependent; now “rager” had been added to my claims. But was that enough to earn a bed in a joint like this?

I walked over to the friends and family meeting in the dining hall and sat in a folding chair next to a client I had befriended. There were about forty people, all seated in a large oval so we could face one another. When it came time for people to volunteer to share their experiences, strength, and hope, someone from my family began talking about me, describing me, sharing stories and facts and traits in a way that felt very wrong, very painful, as if they were taking ownership and credit for the survival skills they thought were so charming, such as my highly inventive fairy world and passion for reading, strategies I had developed to endure and survive their addictions. The tsunami in my body started, and I almost hyperventilated again. Then suddenly I found myself speaking out in front of the whole group, saying, “Please stop! Those are my personal things and it’s inappropriate for you to be talking about me in this way. And by the way, the time frame you are talking about, bragging on me? By the time I was in sixth grade on Del Rio, I was coming home from school and putting a gun to my head on a regular basis, thinking about killing myself.” It was pretty amazing. I had spoken up, shared my reality, debunking powerful single-strand narratives that had dominated the family mythology for decades, and finding the voice—without having to isolate or rage—that I had lost when I was seven years old. Another family member, one who used their voice even less than I and was notable especially for never standing up to anyone, actually spoke up and also asked the person to stop talking about me that way. It seemed a few of us were ready to begin making some big changes.

On Friday, the last day of family week, we met once again in the group room. We each sat with our loved one and said five things we liked and loved about her. We made collages based on suggestions by the treatment team, topics to do with our relationships with one another. It was such a great, loving experience. The staff gave us suggestions about how to support Sister after she got back home, explaining the basics of ED (eating disorder) recovery: no comments about her body. Stay out of her plate when she eats; it’s none of your business. If she is in recovery, you will know from her behavior.

Then they started going around the room and making suggestions for each family member, in some cases recommending Twelve Step programs they should seriously consider attending, books they should read, professional help they might consider. I went last, and the woman who was the head of the treatment team looked at me and said, “We’d like to invite you to stay.”

I was startled. I told them I’d love to come back sometime for the six-day intensive course they offered, but—

“No, Ashley, we’d like to invite you to stay for forty-two days of inpatient treatment. The Band-Aid was pulled off this week. We’d like to help you heal the wound.”

Now I was absolutely staggered. Of course, the thought had already occurred to me, but it was a difficult thing to hear in front of my family, some of whom began clucking about how badly I needed help (oh, the pot calling the kettle black!). I was getting more and more infuriated, feeling that overwhelmed, helpless, voiceless torture again. I felt picked on, when others, with obvious multiple addictions, could also use inpatient treatment. (The staff would tell me later that the invitation was also based on how much hope they felt for me—but I had no way of knowing that yet.)

My head was spinning, and I quietly inventoried my life. I had rock-solid commitments, including a ten-day trip to Central America for PSI. But I knew that trying to tell this bunch, “Oh, but I have this three-country tour with appointments with heads of state, and the military is providing security,” was not an adequate reason, in their eyes, for me to defer going into inpatient treatment. I had already seen the staff convince mothers who were breast-feeding newborns that the best thing they could do for their child was to get clean and sober.

So I knew not to argue or bargain. I sat quietly in the midst of the chaos of my family and looked to my left, and there was Tennie. She looked at me, not saying anything. I kept looking at her, because somehow, in spite of how she seemed to know things about me that I didn’t yet know about myself, things that seemed shameful to admit, she had become my safe person in that room. As I kept looking, something was being communicated to me through her gaze. She had something I wanted. I had no idea what it was, but she had it. It radiated out of her, easily, effortlessly, a sense of recovery, emotional sobriety, and most of all serenity. I kept looking at her, feeling something wordless pass between us. I nodded my head slightly. That was my surrender. I agreed to stay on the spot because of the way she looked at me. Just as I knew I was a Lost Child because “Pets are very important.” That little, but that much.

I returned my attention to the head of the treatment team, who had witnessed my nod. And then Tennie said the most remarkable thing: “Nobody ever thinks to do an intervention on the Lost Child.”

I wanted to bawl as I had never bawled in all my born days, but after showing my family the pain of my anger, I’d be damned before I would show them how much a remark like that cracked me open, especially when I had suddenly, unexpectedly, become the new “identified patient” in the room. As I choked back my enormous swell of emotion, though, I knew in that moment that these people understood something about me that even I didn’t understand. And with very little information, but emerging trust, I made my decision. And as it turns out, there would be plenty of time for deep crying—and the gifts that come with constructive catharsis—ahead.

Chapter 15

THE LOST CHILD FOUND

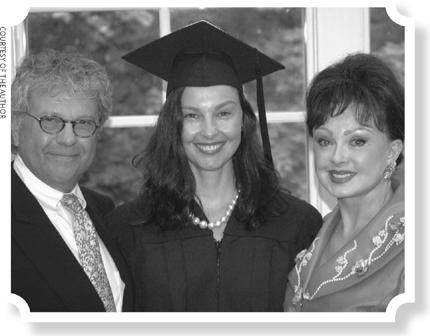

When I received my honorary doctor of humane letters degree, another miracle, conceived in my family week, was born: Both my mother and father attended. I have waited a long, long time for moments like this one.

We think each family which has been relieved owes something to those who have not, and when occasion requires, each member of it should be only too willing to bring former mistakes, no matter how grievous, out of their hiding places. Showing others who suffer how we were given help is the very thing which makes life seem so worthwhile to us now. Cling to the thought that, in God’s hands, the dark past is the greatest possession you have, the key to life and happiness.

—The Big Book of

Alcoholics Anonymous

hey do not mess around at Shades of Hope. My nod was received as a firm “yes,” and I was dispatched from the group room immediately to retrieve my things at the B&B and check into treatment at the front office.

hey do not mess around at Shades of Hope. My nod was received as a firm “yes,” and I was dispatched from the group room immediately to retrieve my things at the B&B and check into treatment at the front office.