All That Is Bitter and Sweet (39 page)

For instance, in the book she described the heartbreaking time when her beloved brother Brian was diagnosed with lymphoma when he was fifteen and she was seventeen. She named the doctor who saw Brian and the type of cancer: reticulum cell sarcoma. She said that her parents made the trip to Ohio with Brian and left her home alone so that she could attend the first day of her senior year. She described the clothes she laid out the night before and the sharpened pencils and notebooks lined up on the dresser. But she did not name the boy who came over that night and, she wrote, “took advantage” of her emotional vulnerability and also took her virginity. By omission, she implied yet again that her occasional boyfriend Michael Ciminella caused her pregnancy.

Unfortunately for everyone concerned, not only did Dad know the truth, but by now so did almost everybody else in our family—and in Ashland, Kentucky. It was an open secret. I remember one family friend, thinking it was normal chitchat, pulling an Ashland High School yearbook off the shelf to show me Charlie Jordan’s class picture, commenting on how much my sister favored him. But astoundingly, unbelievably, none of us had ever told Sister. She was almost thirty years old and she still didn’t know that her biological father was Mom’s old boyfriend Charlie.

When Dad was interviewed by Mom’s collaborator for her memoir, he was put back on his heels to learn the extent of the unflattering things she had been saying about him. He realized that his relationships with his daughters had been poisoned since we were little girls, and he wanted to set the record straight. And he was particularly disturbed that Wynonna still didn’t know the truth about her paternity. Dad had always thought that Sister should be told, but he’d decided it was her mother’s place to tell her.

Finally, with Mom’s book coming out, he decided that the lie had gone too far and that he had to tell Sister himself.

I, too, was tired of all the lying and secret keeping. I occasionally went to family therapy with my mother and sister—something, I have to say, from which I gained minimal benefit, in spite of my fondness for “Joanie,” the practitioner. (I still puzzle over why she didn’t diagnose the addictions or suggest treatment.) But during one such appointment, my mother and sister started arguing about whether Dad should be invited to a concert—the kind of classic power struggle of wounded wills that had destroyed so much of our home life. I watched, really seeing for the first time. For some reason, I didn’t feel so overwhelmed with my own debilitating frustration, helplessness, and pain, and thus I suddenly saw in stark relief the neon pink elephant with a frilly tutu dancing wildly in the room: the Lie. With detachment, I saw the extraordinary energy, the wile, the brilliance, really, that Mom had employed in maintaining the Lie. I knew that for my part, it had to stop. I would soon be done keeping toxic secrets.

The decision to tell Sister was gaining critical mass. Dad attempted to speak to her after she and Mom sang at the 1994 Super Bowl halftime show, but Mom caught wind of his plan and made sure Sister was never alone with him. Mother continued to be tortured by a powerful belief that she would be destroyed if Sister found out, bolstered by her conviction that if she should be told the truth, my sister would need to be “institutionalized.” Dad called Joanie to set up a meeting with my sister so that he could divulge this momentous news in a safe setting.

The night before their appointment, I had a spiritual experience. I remembered the scripture “The truth shall set you free.” I realized it was faith-in-action time. God is everything, or God is nothing. I shared my certainty with Mom.

“Tell her,” I said plainly, flatly, directly, “or I will.” I felt hopeful and sensed freedom was nigh. I had faith beyond the fear.

When Dad arrived at Joanie’s, he was surprised to find Mom’s car parked next to Sister’s. He had been trumped. Mother had booked the appointment prior to his, and I came along to enforce the disclosure. On that day, I made the best decision I knew and decided that my sister was more important than my parents’ court-style intrigue and machinations. What mattered to me was being there for my sister, whichever parent told her.

We sat in Joanie’s office in silence, except for the sound of our mother sobbing. Sister was wondering if she had been summoned to hear more bad news about Mom’s hepatitis. I was in my detached, hyper-rational watching mode again. I was given the gift of some patience, and I waited a while. It eventually seemed clear that it was up to me, because Mom could not go through with telling her. In a strange way, I was happy to have this sober responsibility. I knew … I

knew …

it was right.

“Dad is not your biological father,” I said. “Your father is named Charlie Jordan.”

Mom sobbed and crawled on her knees across the office, burying her head in my sister’s lap.

Sister blurted out something about how this made perfect sense to her and explained some important things she had never been able to figure out. Mother sobbed harder. I watched as my sister’s wheels began to turn, as she began rapidly to process, to finally arrange this information in a way that fit together the puzzle pieces that had been maddeningly scattered her entire life.

In her memoir, Sister wrote, “I wasn’t angry. I wasn’t sad. I wasn’t anything. And I belonged to no one. I felt like I was in a space between earth and hell. I looked at Ashley and saw the pain on her face.… This kind of sorrow never truly goes away. It was devastating for all three of us.”

Although I am not sure it was devastating for me, I was immensely sorry for the years of unnecessary anguish she had endured, all that the lying and evading had cost her. I was sorry, as well, for how much maintaining the Lie had consumed our mother and what it had caused her to do to our dad, her compulsive need to demonize him. Although I imagined her knowing would be an uneven journey, with aftershocks and powerfully mixed emotions, and I couldn’t know how long it would take for there to be acceptance and peace, I knew discarding the lie was a major improvement and held great promise.

Dad says that when he arrived for his appointment, the receptionist told him to wait a bit. Then he, Joanie, and Sister had some time together.

“I’ve just been with Mom and Ashley,” she told him. “Ashley told me.”

“Well, now maybe we can develop a relationship based on truth,” he said.

As you can imagine, there was a great deal of healing to do in our family after that day. Sister and Dad began to build a relationship, having a lot of fun with each other along the way, until they stopped speaking to each other in 1997 after a falling-out over an unrelated matter. Sadly, that’s the way it has always been with our family: one step forward and two steps back.

Chapter 14

SHADES OF HOPE

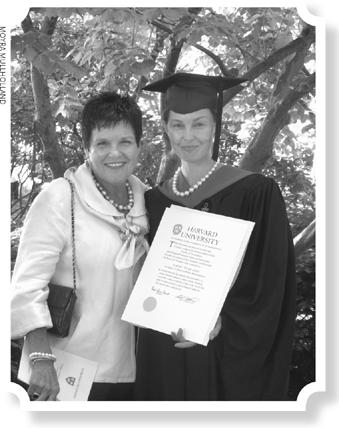

My grandmother of choice, Tennie “Mennie” McCarty, and me at my Harvard graduation.

One cannot begin to learn that which one thinks one already knows.

—EPICTETUS

hrough my sessions with Ted, I was beginning to understand the roots of the depression and behavior disorders that had caused me grief for most of my life. At the same time, my sister was moving toward healing in her own way. As she has said in many public forums, her own painful childhood has fueled an array of problems in her adult life, including a life-threatening eating disorder. Finally, she decided to do something no one in our family had ever done before: seek help for her addictions. It was an enormously brave step, one that would help all of us begin to push back individually and collectively against the inherited, multigenerational dysfunction that often dominated our lives.

hrough my sessions with Ted, I was beginning to understand the roots of the depression and behavior disorders that had caused me grief for most of my life. At the same time, my sister was moving toward healing in her own way. As she has said in many public forums, her own painful childhood has fueled an array of problems in her adult life, including a life-threatening eating disorder. Finally, she decided to do something no one in our family had ever done before: seek help for her addictions. It was an enormously brave step, one that would help all of us begin to push back individually and collectively against the inherited, multigenerational dysfunction that often dominated our lives.

In January 2006, my sister checked herself into rehab at a residential treatment center called Shades of Hope, in the tiny town of Buffalo Gap, Texas. Until then, I had no idea what went on in treatment. Actually, I did not know what rehab was. I had no idea that alcoholism and other addictions were diseases. I didn’t even know my sister suffered from something called compulsive overeating: I just thought she liked to snack, and I certainly didn’t know it threatened her life. I knew a tiny bit about AA from Colleen, the woman who had befriended me in eleventh grade, when I lived mostly on my own in my dad’s apartment. But I had never heard of Al-Anon, which helps friends and families of alcoholics, or Overeaters Anonymous. I mean, for being thirty-seven years old in modern America and someone who’s generally interested in my own well-being, I was completely ignorant about addiction and recovery.

The inpatient program at Shades of Hope lasts forty-two days. During the fifth week of treatment, the family of the patient is strongly encouraged to visit the facility to partake in “family week”—five days of supporting their loved one, which includes evaluating one’s own responses and role in the family system and learning about solutions and tools. When I was invited to attend Sister’s family week, I took a look at the schedule they emailed to me and picked out one day that looked kind of interesting. I called Cam, the administrator, and said, “Okay, great. I’ll be there Wednesday.”

“No,” she said, “it’s really important you be here for the whole five days.”

“Wait a minute, do you have any idea …” I sighed, then explained my work and travel commitments and my husband’s schedule and how it was impossible to cough up five days on short notice.

It was suggested that I call the owner, and I was given her home number. I let that rub me the wrong way. I was already thinking,

Oh, is my family being treated as special and different? Call the owner at home? What’s up with that?

I generally do not appreciate my family being singled out for special attention. Much of our lives have been lived in public since I was a teenager. Stories about the scrappy, struggling single mom, her musical, rebellious daughter, and the constant bickering and fighting between them became integral to the act, the dysfunction became part of the family “brand,” and it’s often been exploited—internally and externally—to my detriment. Additionally, anything we did in public—a movie, a meal after church—became the Judds making an appearance, and I resented the way my mother and sister could not set and maintain boundaries with fans but just welcomed them into what should have been a moment of family time. I have at times also grown terribly weary of the copious amounts of misinformation that have become part of the Judd canon. I once attempted to correct a gross inaccuracy printed in an interview I gave to a British publication. The editor in chief of the magazine responded, “This information is on

The Times

microfiche. We will not change it.” The family myths were increasingly entrenched and apparently incorrigible.