Amazing True Stories of Execution Blunders (4 page)

The general practice was to execute the criminal as near as possible to where they had committed the crime, but eventually more permanent sites were established in open areas rather than in the narrow streets and lanes in order to accommodate the vast crowds which would inevitably gather.

London’s chief execution site was Tyburn, situated by the main road leading into the capital from the north-west, and it was obvious that the spectacle of the scaffold and the corpses of those who had recently been hanged, swaying on the gibbets, would have the been the greatest deterrent to felons entering the City. Its precise site is difficult to determine, but there is little doubt that the scaffold itself stood near the junction of Edgeware Road and Oxford Street (the latter was once named Tyburn Way) and in fact, should one venture on to the small traffic island there, a plaque will be found, set in the cobbles, bearing the words ‘Here stood Tyburn Tree. Removed 1759.’

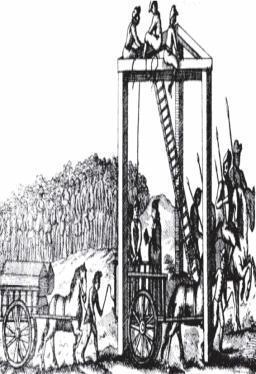

In 1571, in order to increase production – or rather, extermination – the Tyburn gallows were modified, a third upright and crossbar joining the other two. This triangular arrangement allowed a maximum of twenty-four felons to be hanged at the same time, eight from each arm. The ladder method was also replaced, the victims being brought to the scaffold in a cart which halted beneath the gallows just long enough for the malefactors to be noosed; the horse would then receive a smart slap on the flanks, causing it to move away and take the cart, but not the passengers, with it.

The Triple Tree, About 1680

The last execution took place there on 7 November 1783, after which, due to the expansion of the City’s residential suburbs into the Tyburn area, the site was moved to Newgate Prison, executions still being carried out in public outside the walls of that gaol on a portable scaffold which was pulled into place by horses when required. This platform was equipped with two parallel crossbeams positioned over trapdoors: the drop. These were eight feet wide and ten feet long, large enough to accommodate ten felons, and were designed to fall when a short lever was operated. After being noosed and hooded – to conceal their contorted features from the vast crowd of spectators – the victims were allowed to fall a mere three or four feet, thereby dying a slow, lingering death by strangulation, watched by the sheriff and other officials who sat in the comfortable seats arranged at one side of the scaffold.

In England this inhumane ‘short drop’ method remained unaltered until late in the nineteenth century, when executioner William Marwood introduced the more merciful ‘long drop’ method in which the distance the victim had to fall depended on his or her age, weight, build and general fitness. The distance was usually between six and ten feet, death coming almost instantly by the dislocation of the neck’s vertebrae and severance of the spinal cord. It is often thought that hanging immediately arrests respiration and heartbeat, but this is not so. They both start to slow immediately, but whereas breathing stops in seconds, the heart may beat for up to twenty minutes after the drop.

The last public execution in England took place on 26 May 1868 when Michael Barratt was hanged by executioner William Calcraft for attempting to blow up the Clerkenwell House of Correction in order to rescue colleagues imprisoned therein; the explosion resulted in twelve fatalities and many innocent members of the public were injured. After that date all executions took place behind prison walls, a state of affairs deplored by the public at thus being deprived of what they considered to be their rightful – and free – entertainment, and equally deplored by those who supported the abolition of capital punishment altogether, claiming that being in private, without independent witnesses, executions would become even more brutal.

Hanged, Drawn and Quartered

This was the penalty in England and Scotland for those who, by plotting to overthrow the sovereign by whatever means, were charged with high treason. The method of execution was barbaric in the extreme, as exemplified by the death sentence passed on the regicides who had signed the death warrant of Charles I in 1649. At their trial in 1660 it was ordered:

‘that you be led to the place from whence you came, and from there drawn upon a hurdle [a wooden frame] to the place of execution, and then you shall be hanged by the neck and, still being alive, shall be cut down, and your privy parts to be cut off, and your entrails be taken out of your body and, you being living, the same to be burned before your eyes, and your head to be cut off, and your body to be divided into four quarters, and head and shoulders to be disposed of at the pleasure of the King. And may the Lord have mercy on your soul.’

Such appalling punishments were inflicted only on men; women were excused on the grounds of modesty, the reason being, as phrased by the contemporary chronicler Sir William Blackstone, ‘for the decency due to the sex forbids the exposure and publicly mangling their bodies.’ They were publicly burned instead.

The ‘cutting off of the privy parts’ was a symbolic act to signify that, following such mutilation, the traitor would be unable to father children who might inherit his treasonable nature; hardly necessary in view of his imminent decapitation.

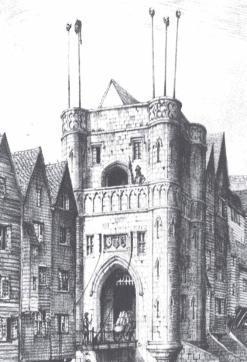

After the half-strangling, evisceration and dismembering of the victim, the severed body parts were displayed in public as deterrents to others who might attempt such foolhardy acts against the sovereign. The heads, after being boiled in salt water and cumin seed to repel the attentions of scavenging birds, were exhibited in the marketplace or a similar venue in the cities in which the traitors had lived and plotted, the quarters being hung on the gates of those cities. In the capital they were spiked on London Bridge where they remained for months until thrown into the River Thames by the Bridge watchman, usually to make room for new arrivals. As at Tyburn, the grisly exhibits were visible warnings to all entering the City from that direction, of the awful retribution meted out to those who came with criminal intent, or sought to overthrow the realm.

Hanged, Drawn & Quartered

From about 1678 the venue was moved, the heads being displayed within the City itself. Although today Westminster is taken to be just another part of London, it was not always so; originally both were separate cities, one demarcation line between them being an archway named Temple Bar positioned approximately at the juncture of the Strand and Fleet Street. The royal coat of arms was emblazoned above the central arch and the stone heads of the four statues which adorned the edifice, those of Charles I and II, James I and Elizabeth I, were soon joined by the human ones from the Bridge, the prominent position of the archway on such a busy thoroughfare guaranteeing maximum publicity and hopefully deterrence.

Heads On London Bridge

Lethal Injection

More a hospital operation than an execution, the process commences with the condemned person initially receiving an injection of saline solution and a later one of antihistamine; the former to ease the passage of the drugs, the latter to counteract the coughing experienced following the injection of those drugs.

A rapid acting anaesthetic is then administered via a sixteen-gauge needle and catheter inserted into an appropriate vein. The victim next receives pancuronium bromide; this not only has the effect of relaxing the muscles, but also paralyses the respiration and brings about unconsciousness. One minute later, potassium chloride is injected, which stops the heart. This sequence results in the victim becoming unconscious within ten to fifteen seconds, death resulting from respiratory and cardiac arrest within two to four minutes – but only if the correct dosages and intervals between injections are strictly adhered to, otherwise the chemical make-up of the drugs changes adversely.

The risk of such mishaps were ever-present when the drugs were manually administered, but were eliminated to a great extent by a talented technician named Fred Leuchter who invented an automatic, computer-controlled machine which, by controlling an intricate system of syringes and tubing, injects the correct amount of chemicals at precisely the right moment. Fail-safe devices and a manual back-up arrangement are also incorporated into the system and a doctor, stationed behind a screen, constantly monitors the victim’s heart condition, thereby being able to confirm the moment of death.

Just as in an execution by firing squad, where a conscience-salving let-out is provided by an unloaded gun, so in an execution by lethal injection, two identical systems are used, neither operator knowing which one is functioning.

Apart from problems brought about by human error or the malfunctioning of components of the system, difficulties also arise in inserting the syringes into the correct vein, especially where it is narrow or unattainable due to prolonged drug taking by the criminal. It is frequently necessary to make an incision in the flesh and lift out the vein in order to insert the needle.

The Scottish Maiden

The Scottish Maiden

It is traditionally believed that James Douglas, Earl of Morton, Regent of Scotland, while returning home following a visit to the English court, passed through Halifax, Yorkshire, and in doing so saw the Halifax Gibbet, a guillotine-type machine, although it predated the French device by many decades. Whether an execution was actually taking place at the time is not known, but suffice it to say that so impressed was the Earl that on arriving in Edinburgh he ordered a similar machine to be constructed. It became known as the Scottish Maiden (Madin or Maydin), a name perhaps derived from the Celtic

mod-dun

, the place where justice was administered.

The axe blade, an iron plate faced with steel, thirteen inches in length and ten and a half inches in breadth, its upper side weighted with a seventy-five-pound block of lead, travelled in the copper-lined grooves cut in the inner surfaces of two oak posts and was retained at the top by a peg attached to a long cord which, when pulled by means of a lever, allowed the blade to descend at ever-increasing speed.