Amazing True Stories of Execution Blunders (7 page)

John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester, was charged with aiding and abetting treason against Henry VIII and condemned to death. The Pope, Paul III, in defiance of Henry’s decision to divorce Katherine of Aragon in order to marry Anne Boleyn, promoted Fisher to cardinal and dispatched a cardinal’s hat to the prelate. On hearing of this, Henry VIII, with savage humour, exclaimed, ‘’Fore God, then, he shall wear it on his shoulders!’

M. Rasmussen

Execution by the axe was the method of capital punishment adopted in Denmark until 1887, when Rasmussen, the leader of a gang of highwaymen, was finally caught and sentenced to death. However, when he was escorted on to the scaffold it was discovered that the executioner, doubtless to steady his nerves for the occasion, had imbibed rather too much strong liquor, with disastrous results. Not only did the first blow go badly awry, the next one did also, and it was not until the drunken axeman had swung the weapon for the third time that the head became completely detached from the torso. So outraged were the Danish citizens at this appalling incompetence that following a judicial enquiry, King Christian IX decreed that all capital punishment, both in private and in public, should be abolished forthwith.

George Selwyn, friend of Horace Walpole, regularly attended public executions and on being reproached for being a spectator at the beheading of Lord Lovat in 1747, riposted, ‘Well, I made up for it by going to the undertaker’s afterwards and watching it being sewn back on again!’

William, Lord Russell

The Rye House Plot of 1683 was a conspiracy to assassinate Charles II and his brother James, Duke of York, near Rye House Farm, Hertfordshire, as they returned from the Newmarket races, a plot in which Lord Russell was falsely accused of being involved. The nobleman was more or less doomed from the start, for his trial was conducted by the Attorney General Judge George Jeffries, who later became known as the infamous Hanging Judge of the Bloody Assizes.

In court Lord Russell asked for a postponement in order to await the arrival of a vital witness. ‘Postponement!’ exclaimed Jeffries. ‘You would not have given the King an hour’s notice in which to save his life! The trial must proceed.’ Thus prejudged and found guilty, the remainder of the trial was a mere formality, and Lord Russell, found guilty of committing High Treason, was sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered, though this was later commuted to just decapitation.

Great efforts were made to save him; his father, the Duke of Bedford, offered the King the phenomenal sum of £100,000 for a royal reprieve, and Lady Russell, the condemned man’s wife, went to the court and, throwing herself at Charles’ feet, begged him for mercy, but to no avail.

On 21 July 1683 the noble lord was escorted to the scaffold erected at Lincoln’s Inn Fields in London, where awaited the other equally terrifying member of the judicial duo, executioner Jack Ketch. The condemned man surveyed the large, jeering crowd surrounding the scaffold and wryly observed, ‘I hope I shall soon see a much better assembly!’

After praying, he removed his peruke (wig), cravat and coat, then handed Ketch ten gold guineas, saying that the executioner should strike without waiting for a sign.

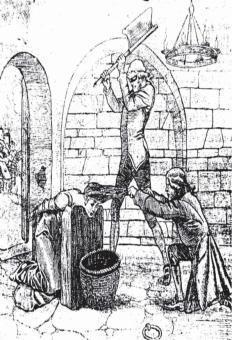

Execution By The Axe

He knelt over the block and Ketch brought the axe down, but only succeeded in inflicting a deep and penetrating wound. Determined to dispatch his victim without further delay, the executioner raised the axe high above his head and brought it down with all the force he could muster; so hard that the blade, passing through most of the victim’s neck, embedded itself in the block to such a depth that Ketch, unable to withdraw it, had to sever the head completely by using his knife before holding it high and, in accordance with tradition, shouting, ‘Here is the head of a traitor! So die all traitors! God save the King!’

Jack Ketch subsequently blamed the peer for the fact that more than one stroke of the axe was necessary ‘because Lord Russell did not dispose himself for receiving the fatal stroke in such a position as was most suitable’ and that ‘he moved his body while he [Ketch] received some interruption as he was taking aim.’

James Scott, Duke of Monmouth

The illegitimate son of King Charles II by Lucy Walters, the Duke of Monmouth raised an army and sought to overthrow King James II, but was defeated at the Battle of Sedgemoor in 1685. Captured and arrested on 13 July of that year, he was later granted an interview with the King, at which ‘he threw himselfe at the King’s feete and begged his mercie. It is sayd he was soe disingenious in his answers to what the King askt of him that the Kinge turned from him and bid him prepare for death.’

After the interview King James wrote, ‘The Duke of Monmouth seemed more concerned and desirous to live and did not behave himself so well as I expected, nor do as one ought to have expected from one who had taken upon himself to be King. I have signed the warrant for his execution tomorrow.’

On 15 July 1685 he was escorted from the Tower by guards and also by three officers, each with loaded pistols, for the Duke was extremely popular with the many members of the public who had little time for King James; so popular indeed, that on arriving on the Tower Hill scaffold he was greeted by a chorus of groans and sighs from the gathered throng of spectators. He looked at Jack Ketch, the executioner so notorious for his savage inaccuracy that his name became synonymous with the very word ‘hangman’. ‘Is this the man to do the business?’ he demanded, and when assured that it was, he prayed, then went over to where the block was positioned with the axe resting against it. Picking it up, he felt the edge of it with his nail, then replaced it and, taking six guineas from his pocket and handing them to Ketch, he said, ‘Pray, do your business well; do not serve me as you did my Lord Russell, for I have heard you struck him three or four times. If you strike me twice, I cannot promise you not to stir.’ Turning to his servant standing next to him, he continued, ‘If he does his work well, give him the other six guineas.’

Observers reported that:

‘he then proceeded to make himself ready. He took his coat off and laid it down, but his peruke he merely tossed aside. Another short prayer, and then with every appearance of calm he laid himself down before the block and fitted his neck into the notches with much precision. But no sooner had he thus settled himself and the executioner begun to raise the axe, than he raised himself on his elbow and said to the headsman, ‘Prithee, let me feel the axe.’ Again he ran his finger along the edge. ‘I fear it is not sharp enough,’ he exclaimed, but the headsman did not like this aspersion on his skill. ‘It is sharp enough, and heavy enough,’ he assured the doubting Duke. And he had the final word. Monmouth fitted his head into the block and shut his eyes to await the end.’

Another report had this description:

‘the executioner first struck an agitated blow, inflicting a small cut, and Monmouth staggered to his feet and looked at him in silent reproach. Then he resumed his place and the executioner struck again and again. Still the head remained on the block, while his whole body writhed in agony. As the horrified fury of the crowd increased, the headsman threw down the axe, crying, ‘I cannot do it. My heart fails me.’ ‘Take up the axe, man!’ roared the Sheriff, while the crowd cried ‘Fling him [Ketch] over the rails!’ So he took it up and hacked away, but the job had to be finished with a knife. A strong guard protected him as he went off, else he would have been torn to pieces.’

Before being buried in the Chapel Royal of St Peter ad Vincula within the Tower of London, the head was sewn back on to the body for a portrait to be painted by Sir Godrey Kneller, and it is now displayed in London’s National Portrait Gallery.

In the Tower of London, awaiting decapitation by the axe for treason against Henry VIII, John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester, discovered that his cook had failed to produce dinner that day. On being questioned, the man explained, ‘It was common talk in the town that you should die and so I thought it needless to prepare anything for you.’

‘Well,’ retorted John Fisher, ‘for all that, thou seest me still alive; so whatever news thou shalt hear of me, make ready my dinner, and if thou seest me dead when thou comest, eat it thyself!’

Boiled in Oil

Loys Secretan

In 1488 the tables were neatly turned in the French city of Tours, when the victim, who should have died, didn’t, and the executioner, who shouldn’t have died, did! Death by immersion in boiling oil was the method of capital punishment in those days, and it so happened that a convicted coiner named Loys Secretan was due to be executed in that manner in the Place de la Fere-le-Roy. Everything went drastically wrong, at least for Denis, the executioner.

‘He took the said Loys on to the scaffold and bound his body and legs with cords, made him say his ‘

in manus

’, pushed him along and threw him head first into the cauldron to be boiled. As soon as Secretan was thrown in, the cords became so loose that he twice rose to the surface, crying for mercy. Which seeing, the provost and some of the inhabitants began to attack the executioner, saying, ‘Ah, you wretch, you are making this poor sinner suffer and bringing great dishonour on the town of Tours!’

The executioner, seeing the anger of the people, tried two or three times to sink the malefactor with a great iron hook, and forthwith several people, believing that the cords had been broken by a divine miracle, became excited and cried out loudly, and seeing that the false coiner was suffering no harm, they approached the executioner as he lay with his face on the ground, and gave him so many blows that he died.

Charles VIII pardoned the inhabitants who were accused of killing the executioner, and as for the coiner of false money, he was taken to the church of the Jacobins for sanctuary, where he hid himself so completely that he never dared to show his face again.’

Found guilty of committing high treason against James I, George Brooke was condemned to be executed by the axe in the courtyard of Winchester Castle. When he was ordered to lay his head on the block, he told them that ‘they must give him instructions what to do, for he was never beheaded before!’

Branding

Comtesse Jeanne de la Motte

One of the most famous cases in which a criminal was disgraced by being disfigured with a brand occurred in France in 1786, the criminal being no less than a lady of society, Jeanne de Saint-Valois, wife of the Comte de la Motte. A witty, elegant and attractive woman, she had become acquainted with Cardinal de Rohan, a man with powerful influence at Court, and she managed to persuade the prelate that she was a close friend of the Queen.

Her ingenious scheme revolved around a magnificent necklace made by the crown jewellers, MM. Boemer and Bossange, on behalf of King Louis XV for his mistress Mme du Barry. However, the King died before it could be completed, and du Barry was exiled to England, so the necklace, which consisted of no fewer than 541 precious stones, was offered to the new King. Its price, 1,800,000 livres, was considered too high, and so the jewellers offered to make a valuable present to whoever could find a buyer.

Comtesse de la Motte wove her plot skilfully, telling the Cardinal that the Queen wanted to buy the necklace with her own money without the King’s knowledge, and so desired the Cardinal to buy it on her behalf. She produced an authorisation forged by an ally named Marc-Antoine Retaux de Villette, purporting to be from the Queen, pledging payment to the jewellers.

Accordingly the necklace was given to the Cardinal, who in turn passed it over to the Comtesse for delivery to the Queen – except that it never reached the royal palace. Instead Jeanne de la Motte sold some of the gems, her husband taking the remaining stones to England, where he promptly disposed of 300 of them for £14,000: a veritable fortune in those days.

The jewellers, having received no payment, complained to the palace and enquiries were begun, with the result that all involved, including Jeanne, the forger Villette, and the Cardinal were put on trial. The latter dignitary was cleared of all blame but Villette was sentenced to be banished from the kingdom. Jeanne de la Motte was found guilty of initiating the plot, the sentence being that she should be whipped, branded on both shoulders with the letter ‘V’ (

voleuse

, thief), and imprisoned for life.

On hearing the sentence, Charles-Henri, the public executioner, sought clarification of that part which stipulated that the prisoner should be ‘beaten and birched naked’; the ambiguous reply he was given was that he was to arrange the affair to take place as discreetly as possible, and to temper the severity of the sentence with humanity. The Comtesse was not aware of the sentence for, as was the judicial custom, the horrific details would not be disclosed to her until the actual day on which they were to be administered.