Amazing True Stories of Execution Blunders (2 page)

PART ONE:

METHODS OF TORTURE AND EXECUTION

METHODS OF TORTURE

The Boots

Among the tortures mentioned in this book, many chroniclers believe that the ‘boots’ ranked high among those available to the courts; indeed, some called it ‘the most severe and cruell paine in the whole worlde.’ Whichever variety of this device was used, the victim, even if not subsequently executed, was invariably crippled for life. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries this particular method of persuasion was popular in France and Scotland (where it had the deceptively whimsical-sounding name of ‘bootikins’), and so distressing was the sight of a victim undergoing this torture that, as Bishop Burnett wrote in his

History

, ‘when any are to be struck in the Boot, it is done in the presence of the Council (of Scotland) and upon that occasion almost all attempt to absent themselves.’ Because of the members’ reluctance, an order had to be promulgated ordering sufficient numbers of them to stay; without a quorum, the process of questioning could not begin.

One type of the device was a single boot made of iron, large enough to encase both legs up to the knees. Wedges would then be driven downwards a little at a time, betwixt leg and metal, lacerating the flesh and crushing the bone, and incriminating questions asked following each blow with the mallet.

Another version, known as the ‘Spanish Boot’, consisted of an iron legging tightened by a screw mechanism. Heating the device until red-hot either before being clamped on the legs or while being tightened was an additional incentive to confess.

Another type of high boots were made of soft spongy leather, and were held in front of a blazing fire while scalding water was poured over the fiendish footwear. Alternatively, the victim might have to don stockings made of particularly pliable parchment, which would then be thoroughly soaked with water. Again subjected to the heat of the fire, the material would slowly dry and start to shrink, the subsequent excruciating pain soon extracting a confession.

Boiling Water In Boots

Branding

While not an actual torture or a method of execution, it was nevertheless a penalty administered by the executioner and so was equally liable to go horribly wrong. Branding, from the Teutonic word

brinnan

, to burn, was used in many countries for centuries and was applied by a hot iron which seared letters signifying the felon’s particular crime into the fleshy part of the thumb, the forehead, cheeks or shoulders. More appropriately, blasphemers sometimes had their tongues bored through with a red-hot skewer.

Branding With Red-Hot Iron

In England the iron consisted of a long iron bolt with a wooden handle at one end and a raised letter at the other. The letters allowed everyone to know not only that someone was a criminal, but also what particular type of crime had been committed, having ‘SS’ for Sower of Sedition, ‘M’ for Malefactor, ‘B’ Blasphemer, ‘F’ Fraymaker, ‘R’ Rogue and so on.

Until the practice was abolished in 1832, French criminals were similarly disfigured, the brand being made even more prominent by the application of an ointment comprised of gunpowder and lard or pomade. In medieval times all felons had the fleur-de-lys brand but later forgers had ‘F’; those sentenced to penal servitude, ‘TF’ (

travaux forcés

); for life imprisonment, ‘TPF’ (

travaux forcés à perpétuité

) and so on.

The Rack

As with other instruments of torture, many different types existed but the basic design of the rack consisted of an open rectangular frame over six feet in length that was raised on four legs about three feet from the floor. The victim was laid on his back on the ground beneath it, his wrists and ankles being tied by ropes to a windlass, or axle, at each end of the frame. These were turned in opposite directions, each manned by two of the rackmaster’s assistants; one man, by inserting a pole into one of the sockets in the shaft, would turn the windlass, tightening the ropes a fraction of an inch at a time; the other would insert his pole in similar fashion but keep it still to maintain the pressure on the victim’s joints while his companion transferred his pole to the next socket in the windlass. The stretching, the gradual dislocation and the questions would continue until the interrogator had finally been satisfied.

A later version reduced the need for four men to two by incorporating a ratchet mechanism which held the ropes taut all the time, the incessant and terrifying click, click, click of the cogs and the creaking of the slowly tightening ropes being the only sounds in the silence of the torture chamber other than the shuddering gasps of the sufferer.

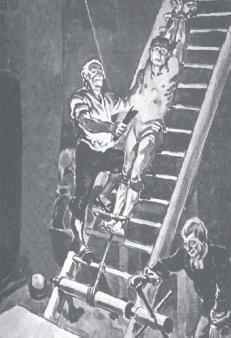

The ‘Ladder Rack’ was employed in some continental countries. As its name implies, it consisted of a wide ladder secured to the wall at an angle of forty-five degrees. The victim was placed with their back against it, part way up, the wrists being bound to a rung behind at waist level. A rope, tied around the ankles, was then passed round a pulley or roller at the foot of the ladder which, when rotated, pulled the victim down the ladder, wrenching the arms up behind, causing severe pain and eventually dislocating the shoulder blades. To add to the torment, and further encourage a confession, lighted candles were sometimes applied to the armpits and other parts of the body.

The Ladder Rack

Where it was considered that wider publicity would have a greater deterrent value, felons were racked in the open, usually in the marketplace. For that purpose a different version of the rack was utilised. The victim had to lie face-upwards on the ground; arms bound behind and wrists pulled up and secured to a stake. A long rope, tied about the ankles, was then wound around a vertically mounted windlass, the shaft of which, similar to other models, was pierced with holes so that the executioner’s minions could insert poles and so rotate it, thereby imposing continuous and maximum strain on the victim’s limbs. This version not only dislocated hip and leg joints but also inflicted extra strain on the shoulder blades and elbows because of the already contorted position of the criminal’s arms. And should any additional punishment be deemed necessary, the executioner would deliver measured blows with an iron bar.

Water Torture

The Water Torture

This method of persuasion required the prisoner to be bound to a bench, a cow-horn then being inserted into his or her mouth. Following a refusal to answer an incriminating question to the satisfaction of the interrogators, a jug of water would be poured into the horn and the question repeated. Any reluctance to swallow would be overcome by the executioner pinching the victim’s nose. This procedure would continue, swelling the victim’s stomach to grotesque proportions and causing unbearable agony, either until all the required information had been extracted, or until the water, by eventually entering and filling the lungs, brought death by asphyxiation

.

METHODS OF EXECUTION

The Heading Axe and Block

Being dispatched by cold steel rather than being hanged was granted as a privilege to those of royal or aristocratic birth, it being considered less ignoble to lose one’s life as if slain in battle, rather than being suspended by the hempen rope. Such privilege did not necessarily make death any less painful; on the contrary, for although being hanged brought a slow death by strangulation, the axe was little more than a crude unbalanced chopper. The target, the nape of the neck, was small; the wielder, cynosure of ten thousand or more eyes, nervous and clumsy; and even when delivered accurately it killed not by cutting or slicing, but by brutally crushing its way through flesh and bone, muscle and sinew. It was, after all, a weapon for punishment, not for mercy.

Most English executions by the axe took place in London, the weapon being held ready for use in the Tower of London. The one currently displayed there measures nearly thirty-six inches in length and weighs almost eight pounds. The blade itself is rough and unpolished, the cutting edge ten and a half inches long. Its size and the fact that most of its weight is at the back of the blade means that when brought down rapidly the weapon would tend to twist slightly, throwing it off aim and so failing to strike the centre of the nape of the victim’s neck. Unlike hangings, executions by decapitation were comparatively rare events, the executioner thereby being deprived of the necessary practice.

A further factor was that the axe’s impact inevitably caused the block to bounce, and if the first stroke was inaccurate and so jolted the victim into a slightly different position, the executioner would need to readjust his point of aim for the next stroke: no mean task while being subjected to a hail of jeers, abuse and assorted missiles from the mob surrounding the scaffold.

The heading axe’s vital partner, the block, was a large piece of rectangular wood, its top specifically sculptured for its gruesome purpose. Because it was essential that the victim’s throat rested on a hard surface, the top had a hollow scooped out of the edges of each of the widest sides; at one side the hollow was wide, permitting the victim to push their shoulders as far forward as possible, the hollow on the opposite side being narrower to accommodate the chin. This positioned the victim’s throat exactly where it was required, resting on the flat area between the two hollows. Blocks were usually about two feet high so that the victim could kneel, although the one provided for the execution of Charles I was a mere ten inches in height, requiring him to lie almost prone and thus induce in him an even greater feeling of total helplessness.