American Eve (30 page)

Authors: Paula Uruburu

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Historical, #Women

As each day passed, the quarreling between mother and daughter escalated, until finally Mrs. Nesbit demanded that Thaw send her back to America. Harry knocked on Evelyn’s door. She answered, and when he told her of her mother’s demand, she said she couldn’t take the strain any longer; she said she would go off either by herself or with Harry if that’s what her mother wanted. The desperation in her voice made Harry hopeful that once again he could rescue his damsel, this time from a distress he had carefully orchestrated.

Harry moved Evelyn and her belongings to another hotel near Oxford Circus. When Harry went back to reason with “the unreasonable Mamma,” he found her talking to his “acquaintance turned cad,” Craig Wadsworth, the man who had invited Harry to White’s Tower party several years earlier and who, coincidentally, was an attaché at the American embassy. Wadsworth told Harry that Mrs. Nesbit had been in touch with him and wanted to make a complaint against Thaw at the embassy—and if need be, against Evelyn. Harry feigned surprise and laughed, but secretly wished he could widen the rift between “the stupid mamma” and his “Boofuls,” who knew nothing of either’s machinations. The wedge, however, had been solidly driven between Evelyn and her mother, and it was sufficient enough for Evelyn to agree to leave her mother stewing in London while she and Harry returned to the City of Light. Harry arranged for the two of them to have separate but adjoining suites in the Ritz Hotel. He said he would hire a new chaperone from an agency as soon as possible, all the while plotting the next phase of his own grand, nasty scheme.

THE CONFESSION

Having achieved what he had set out to do—have his Angel-Child entirely to himself by cutting all but the one cord he was tightening around her (having severed her completely from friends and family who were either a channel or an ocean away)—Harry then seized the opportunity to force the issue of marriage with her. Again.

After only a few days in Paris, Harry entered Evelyn’s suite as evening approached, looking haggard and worried.

“I want to speak with you,” he said in great earnest, and then without any preliminaries, he blurted out: “I want you to marry me!” With her

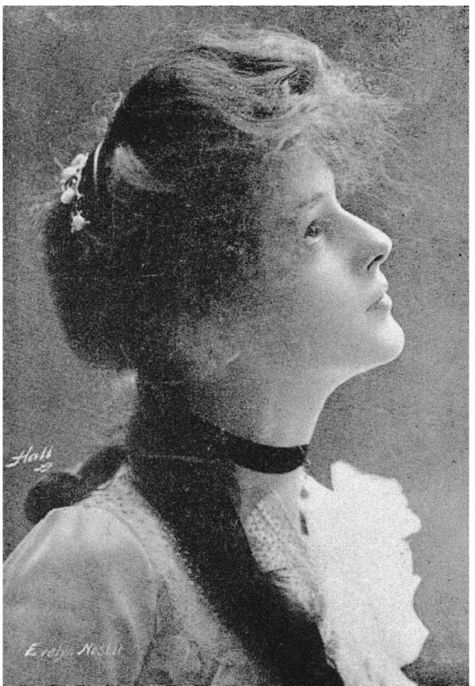

Evelyn on arcade postcard frequently

titled

The Dawn of Hope

.

mother gone, and alone in the room in a foreign city “without a sou,” Evelyn realized there was no exit. As she describes it, there was “no fending him off with excuses, with reasons or with explanation as to why marriage was not desirable,” especially since he had been so kind, so gentle, and so amazingly patient and understanding. He insisted he had to know why, since he had already shown her he was willing to lay the world at her dainty feet, and she in turn had begun to respond favorably to his tokens of affection.

Like a songbird in a Pennsylvania coal mine, a trapped Evelyn on the verge of physical exhaustion began to get light-headed. She gripped the arms of her chair until her knuckles turned white and she felt as if the floor, along with the Ritz’s elegant Persian rug, was about to be pulled out from under her. She had the sensation of being dragged “down and down into a dark rabbit hole.”

“I must know the truth,” Harry suddenly insisted, thumping his fist on the back of her chair. Her mind sprinted, then raced to weigh the consequences of actually telling him the dreaded truth. Moving to the other side of the room, Thaw began to babble incoherently under his breath and performed a kind of figure eight, almost knocking over an expensive vase. Knowing his preoccupation with virginity, Evelyn figured that Harry would surely and swiftly brand her wanton and unworthy of his attentions if she revealed “the secret.” Her mother’s shuddering rage after her night out with Jack flashed into her mind. She considered that at best, Harry might leave her stranded in Paris just as he had left her mother in London. Or, even worse, he might become violent, as he had with the bellboy. Like a spoiled mastiff, Thaw was a yelping and tenacious interrogator, and Evelyn could take his “Harrying” no longer. Frightened yet almost oddly relieved that the abominable truth she had carried for so long was about to be unleashed (after all, following White’s directions, she had never told a single person), an emotionally, mentally, and physically exhausted Evelyn wavered. She stated one more time, “I cannot marry you.”

“Why not?” Harry pleaded. “Do you not love me?”

Evelyn shook her head, indicating that it was something more serious, although she didn’t say that she loved him, either.

“Then why?” he repeated.

Evelyn hemmed and hawed and hemmed, then began slowly and deliberately, saying, “Because.” But she paused, as if trying to catch her breath. Harry ran his hands violently through his hair in an exaggerated version of one of Stanny’s characteristic gestures, and waited as oily perspiration began to form on his upper lip.

After months and months of Harry’s hounding and challenging her to explain her stonewalling, Evelyn’s resolve crumbled and her common sense collapsed into dust. And then she made the worst mistake of her life. She decided to tell Harry the truth about the “Burglar-Banker-Father” who had stolen her innocence in the guise of guardian and friend.

As she began again, Harry, who was still on the other side of the room pacing with nervous agitation back and forth, walked toward her and laid his large, soft, and clammy hands on her slim shoulders. He looked straight into her frightened eyes with a lemurlike stare and asked (as if he didn’t know), “Is it because of Stanford White?”

Evelyn hesitated, then nodded in the affirmative. He prompted her: “It’s all right, you can tell me about your relationship with Stanford White. . . . Tell me everything,” he said, in a strange, panting voice filled with dread and anticipation.

“All right,” Evelyn said, again faltering. “Sit down and I will tell you everything.”

The moment Harry had feared, obsessed over, squirmed about, and prayed for was upon him. Finally he would have incontrovertible proof of White’s reprehensible behavior with vulnerable, unsuspecting young girls. And he would have the Angel-Child, White’s most prized possession, as his trump card. A wave of ecstasy washed over him.

As she described it in 1915, Evelyn told him the tale of her ruination slowly and with great deliberation, unintentionally fanning Harry’s already smoldering torment. It was a difficult story to tell, not only because she remained with White as his mistress after his disgraceful seduction of her, but because she feared what Harry’s reaction would be once she confirmed his worst fears. The frequent pauses, while not calculated, teased and goaded him. He gaped, openmouthed; would shudder, then go limp; he rose and fell with each tortured sentence and hung, moist-eyed, on every word. But as Evelyn described it, “[I made] no excuse for myself, giving no place to prejudice against White,” which was not what Harry wanted to hear. Once she started, she found she could not stop: “I told him all that had happened since the very beginning.”

As she proceeded with her narrative, Evelyn sat stiff-backed on the edge of her chair, her hands in her lap nervously working into tight knots an Irish lace handkerchief Harry had given her. Evelyn told Harry how her mother had been convinced to go out of town by White, who assured her he would watch over her (even though family on her father’s side had offered to take both Evelyn and Howard in with them). She described the mirrored room and bed, and how White had given her several glasses of champagne. How the next thing she knew, he had “had his way with her” while she remained unconscious. The moment she reached the climax of her tale, Evelyn watched in amazement as Harry rose slowly, then pitched himself with his full force into a chair; he buried his face in his hands, and began to paw at his cheeks and sob hysterically.

“Poor child!” he muttered repeatedly. “Poor child!”

Then, instead of spontaneously combusting, Harry’s body went momentarily limp. His hands began to shake uncontrollably. His face “was ghastly. . . . He rose and walked up and down the room, gesticulating as he muttered.” Affected by the vehemence and apparent sincerity of Harry’s distress over her ordeal and her own overwhelming cathartic turmoil at having finally told someone about that night, Evelyn also burst into hot tears. She held her stomach, fearful of becoming sick or rupturing her stitches. Periodically Harry would get up and prowl across the room, biting his thick bottom lip and emitting loud moans. He walked back toward her, crying, “Oh, God! Oh, God!” and then prompted her with, “Go on, go on, and tell me the whole thing.”

The two of them sat up all night, with Evelyn crying off and on for hours, until the hour arrived when her tongue turned to sandpaper. Then she fell silent. At first, Harry whimpered almost imperceptibly. Then he began to make wounded-animal noises eerily reminiscent of the sounds her mother used to make during her “attacks of grief.” He began to wring his hands like a ham actor in a cheap melodrama. He gnashed his teeth, pulled at his hair from the roots, and then turned his anger on Mrs. Nesbit.

He accused Evelyn’s mother of horrifying negligence and sinful abuse. Evelyn tried to defend her mother, saying that her only fault was naiveté. She told Harry that she had willfully deceived her mother in accordance with White’s orders since that awful night (and perhaps began to consider how she had obeyed her mother’s orders that night as well). Then she fell silent again. Harry, too, finally became quiet, and Evelyn began to mull over what he had said about her mother’s foolish, self-serving neglect. Evelyn knew that she had frequently felt her mother silly, which in turn caused the hardheaded girl to act with deliberate impudence. A nearly spent Harry breathed heavily as if on the verge of a stroke, yet continued to question Evelyn as to her mother’s knowledge of the “horrid affair.” Did she know anything about her child’s maidenly downfall at the hands of a satyr? he asked several times. Evelyn put her head down, but insisted her mother did not know. Harry then assured his Angel-Child that any decent person who heard this story would say that it was not her fault, and that he didn’t think any less of her because of it. But he wasn’t as sure as he sounded. Nor was he decent.

Evelyn looked at Harry, who made for a pious picture on his knees, his hands folded together like Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane. His red-rimmmed eyes stared heavenward as he began to speak out loud, but in curses rather than prayers. He had known all along that he was right about Stanford White. He had been horribly yet triumphantly vindicated. He rambled incoherently at times, as if speaking in tongues, then knelt at Evelyn’s side as he had when they first met and as he had just before she went under the surgeon’s knife. He gently took her hand and stroked it in sympathy. Evelyn was overwhelmed and saw Harry in a significantly sympathetic light—“all that was best in Harry Thaw . . . all the womanliness in him, all the Quixote that was in his composition . . . a shining light.” But it was a ghost light, and in her own confused and turbulent state, Evelyn did not see how her story also excited Harry in a very different way.

Harry assured her that he would always be her friend. He said that at that moment in the huge drawing room, in her long blond wig tied loosely with a ribbon, Evelyn looked to him like Alice in Wonderland, “so lovely and truly so innocent, it singed one’s soul.” He told himself that, “all would have been so natural if her father had lived,” that her mother was guilty of hideous negligence, and that her mother’s behavior in response to White was “unnatural” (a word that would reappear with frequency during the trials). He also said he believed that poor little Evelyn had never acted “[of] her own volition unless she had refused point blank her mother’s order to obey a beast.”

In his own account of his reaction to Evelyn’s “hideously awful tale,” Harry claims (disingenuously) that he tried “again and again, moment by moment to find some possible excuse” for White’s behavior, but realized once and for all that the admired and fêted architect was a vicious sexual predator.

Throughout the marathon confession, Harry pressed Evelyn to tell him every detail she could ever remember about White. As the night wore on and Evelyn stared out the window, the fabled lights of the city of love seemed to dissolve. Neither she nor Harry heard the rumblings of carriages or the sounds of an occasional motorcar, which gradually faded, then returned with the first light of day.

After the harrowing night of Evelyn’s admission to “filthy ruin,” the other unpleasant situation, the stewing Mrs. Nesbit in London, had approached its boiling point. Having been “stranded” for almost a week, with the faithful Bedford acting as gentleman-in-waiting for her and Harry paying $1,000 for expenses that had been run up in that week alone, Mrs. Nesbit took matters into her hands the only way she knew how—she cabled Stanford White for money to come home.

Mrs. Nesbit also began official proceedings to charge Thaw with the crime of “corrupting the morals of a minor,” whom he had transported from country to country. Insinuating that Thaw had kidnapped her daughter, Mrs. Nesbit found herself in a position of power, if only temporarily. Initially, Harry laughed and tried to pass it all off as a “tempest in a teacup.” Then he called his business lawyer, a Mr. Longfellow, who said he would look into it, but that Harry should be very cautious of criminal charges, especially in a foreign country. Since technically Evelyn was “seventeen and three-quarters old,” the charge Mrs. Nesbit made against Harry was valid. And if he continued on his present course, there would an armory full of legal ammunition aimed against him. He needed to be scrupulously careful “while traveling with the girl on the Continent.” He told Harry in no uncertain terms that he could not cross any more lines. It fell, of course, on wild, deaf ears.