American Eve (34 page)

Authors: Paula Uruburu

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Historical, #Women

As Evelyn came to see it, it must be said Mother Thaw did everything she could to prevent the marriage. She acted as any mother would have done who thought she saw a “misalliance.” But it was not Mother Thaw’s intemperate concern for her son that bothered Evelyn. It was her snobbery. As far as Evelyn was concerned, the Thaws acted as if they had made their money within one generation from coke and railroad dealings, and could make no great claims to the kind of social standing that comes from “old money,” even though they had “more money than God,” as one paper reported. And as Evelyn stated, they were “extremely rich, and I . . . was extremely poor. And Society in Pittsburgh is governed by the initials which indicate the Almighty Dollar.”

Even as Mother Thaw continued to serve God through various philanthropic activities affiliated with the Third Presbyterian Church, she maintained a rather un-Christian attitude toward Evelyn. For more than a year she resisted Harry’s pleas to marry Evelyn, on the grounds that it would be the ruination of the family name. A surprised Harry, who had been so accustomed to getting his way with his mother, persisted. He told her, in what Evelyn called an exaggeration, that she possessed “a beautiful mind.” As Evelyn put it, “healthy” would have been a better word to describe her mind, for she had come to the time when she saw things in “their true proportions.” But Harry was prone to exaggerating the virtues of his friends and the failings of those he regarded as his enemies. Harry saw the world in those terms—friend or foe. There was no middle ground between the two in his feverish mind.

Once a distracted and despairing Harry returned to Lyndhurst for Thanksgiving, unable to believe that a sickly and fiscally vulnerable Evelyn could continue to turn him down and remain in the “shadow of the Beast,” it looked to his mother as if “he had lost interest in everything. ” At breakfast he seemed unusually absentminded, as if laboring over a grave problem. Without warning Harry got up from the table, went into the parlor and played the piano violently at first, then more softly; a few minutes later he returned, as if nothing had happened. He repeated this several times, even while there was company at the table. After a few days it was clear that he was no longer sleeping; she could hear smothered sobs coming from his room, sounds that must have wreaked their own kind of havoc on her, if only subconsciously. Once when she went into Harry’s room at around four in the morning, she found him sitting on his bed, fully dressed, staring into the darkness. But he refused to tell her what was wrong. Finally, she insisted. In a torrent of words, Harry told her all the details of Evelyn’s sad tale of maternal negligence and sexual ruin. Mother Thaw reacted somewhat sympathetically, but warned Harry not to get caught up in such a tragic case, one where the sins had already been committed and he therefore could do nothing to change those facts. It was not a situation “that allowed for salvation.”

The next day in the new Third Presbyterian Church at Thanksgiving morning services, an odd little scene took place between Harry and his mother as they sat in the back under the gallery. They were the only two from the family at the service, as his sisters were coming for the holiday from England and New York but hadn’t yet arrived. Despairing and desolate that Evelyn was effectively avoiding him, having chosen to go back to the theater and the sphere of White’s influence, and unhappy with his mother’s lack of sympathy, Harry stood next to Mother Thaw throughout the service. Toward the close, the choir began to sing Kipling’s Recessional Hymn. Without warning, Harry began to sob, swallowing intermittently and emitting his wounded-animal noises. Mother Thaw gave him a little shake as his tears fell on the hymnal in his trembling hands.

After church, she tried to discuss the matter with the gloomy Harry. Near tears again, Harry told his mother that he had tried to discourage the girl from life on the stage and offered to send her to school and so forth but that “he had very little help or encouragement from her mother in his efforts to protect or befriend the child,” as he constantly referred to her. A week or so later, Dr. Bingman, a family friend who knew Harry’s medical and “emotional” history, came to talk to him. He was utterly depressed, even more than when he had tried, halfheartedly, to commit suicide by cutting his own throat in his days at Wooster Academy. Finally, fearing a potentially more effective suicide attempt, Mother Thaw relented. She gave Harry her reluctant approval to pursue his fallen angel.

A thoroughly elated and invigorated Harry returned to New York in December. He kept up a steady campaign of penitent courtship; he sent gifts and the contents of an entire florist’s shop with notes indicating that he had changed and that he still wanted to marry her. When Evelyn sent some clothes of his that had been in her trunk, one of the pockets had an ivory nail file of hers in it. Harry took this as a sign “that everything was all right.”

What developed in the days leading up to Evelyn’s eighteenth birthday was a Mexican standoff in the middle of Manhattan. White’s lawyers were armed with the affidavit and other evidence of Thaw’s concealed criminal behavior, a large portion of it provided by Mrs. Nesbit (including shirtwaists she said Thaw in fits of anger had ripped from her daughter, which she had kept as evidence). Thaw and his lawyers were armed with Evelyn’s story, combined with mounting evidence from other young “victims” of White whom Harry, with the help of his detectives and the prehensile grasp of Comstock’s Society for the Suppression of Vice, had ferreted out. Thaw was also paying part of his army of detectives to watch White’s every movement, while White paid out close to six thousand dollars in several months to his own detectives to find out who was paying to have him watched. But with White’s potentially devastating threat hanging over Harry’s head, his lawyers advised him not to do anything rash until Evelyn turned eighteen. So, the overwrought Harry waited like an excitable child for Christmas Eve.

In the meantime, what with costume fittings, pre-show parties, and some modeling assignments, Evelyn tried to throw herself into her new role with enthusiasm. But nothing had changed. Even though Stanny was still willing to make himself and his money available to Kittens, his unwavering interest in other girls was too blatant and insulting. Meanwhile, he had effectively diminished her reputation for any potential legitimate suitors within his considerable sphere of influence. Which left her in limbo.

The morning of December 24, Harry sent all sorts of gifts to Evelyn’s hotel—Japanese trees, bonsai miniatures—and, according to his own recollection in his memoir, “she cared little.” For his part, Stanny was planning a “bully party” in honor of Evelyn’s eighteenth birthday at the Tower.

That evening, Harry—along with two friends, Charlie Sands and Lorimer Warden, and an unnamed girl—drove to the Madison Square Garden Theater, where Evelyn’s show had opened. According to Harry, they had expected to find Kennedy, the detective from the Grand Hotel (and one of Harry’s informants as to Evelyn’s comings and goings) waiting outside. Instead, there was a Detective Heitman, who told Harry that White was not there. Moreover, he told Harry that he had overheard four members of the Monk Eastman gang talking and pointing to Harry as he stepped out of the carriage. An anxious Harry, full of false bravado, went into the theater to watch the play. After the performance, Harry went to Evelyn’s dressing room, where “a colored maid was helping her.” It would be at least twenty minutes before she was ready, so he again went outside.

There he met with Kennedy and the other detective. When they agreed that there had been Monk Eastman gang members in the vicinity, Harry asked one of the men for his revolver. He took the gun and walked with Lorimer across the street into the saloon, where the four gang members were supposedly in a back room. Harry wondered whether or not the detectives might be lying, and went outside just in time to see a large black electric hansom drive up to the theater. An elegant, darkly dressed man got out and ran across the street in a hurry toward the stage entrance. It was Stanford White.

Within ten minutes or so, an apparently “wild and excited” White came out “looking like everything was wrong.”

What had happened was that Evelyn had decided she did not want to go to White’s party and continue with tiresome and disheartening patterns that held no promise of anything better in her personal future. White had urged her to come to the Tower, and she hotly refused. He then told her that he would give her time to cool off. Soon after White left, Harry picked up Evelyn, and she, along with his two friends and the girl, went instead to dinner at Rector’s, the place she and Harry had first met. Harry was flushed with excitement at frustrating White on the very day his lawyer, Longfellow, said he could start his reconciliation with Evelyn without fear of the law. One has to wonder how soon after her fateful decision Evelyn began to regret it, since Harry’s description of the evening of her eighteenth birthday seems anything but happy: “The little party at Rector’s was one of repentance, not of the food nor of the wine nor Evelyn, but her rape by White.”

Another thing that ate away at Harry was the idea that White continued to provide funds for Evelyn’s brother even while he, Harry Thaw, was fully capable and willing to do so. Harry had assumed or had been told (it’s not clear which) that Mr. Holman, her new stepfather, had taken over the financial care for Howard. But when Harry discovered that it was not the case, that Howard actually worked for White in some minor capacity, perhaps as an assistant to his secretary, he became more disturbed and angry at Evelyn’s mother, who had let both her children be “bamboozled” by White. He also took this as a sign that White still wanted to have some leverage over Evelyn, whom he could twist to his will.

Harry knew that the great architect gave her a weekly allowance when she was not working, and “he paid the same sum for that brother—very generous, you see, when he hoped to ‘get her back.’ ” Harry also began to think, as did others, that perhaps White’s well-known princely generosity was a way of offsetting deeds “committed out of unscrupulous passion”— that White was “a bookkeeper with the Fates” who tried out of remorse or guilt to salve his conscience and unpleasant memories by doing good deeds.

According to Evelyn, a few days later, Sam Shubert, the theatrical manager and co-producer of her show (who died tragically in a train wreck in May), had told her with innocent amusement that White was in a great state of excitement that night, both at the theater and at the Tower party, where he kept jumping up from the table and checking for Evelyn, “running out and then coming back in again.” Finally, he said, White went back to the theater, where, apparently, he had just missed her. When White questioned the stage doorman, Benjamin Bowman, he was told she had left with Thaw. First, calling Bowman “a goddamned liar,” an agitated White ran into the theater, and finding no Evelyn, came back out. He then allegedly pulled out a revolver of his own and waved it in front of Bowman, vowing he would find and “kill the son of bitch before daylight.” Four days later, Bowman stopped Harry Thaw on the street and told him of the remarks White had muttered about “that miserable puny Pittsburgher.”

As the weeks went by, the antagonism between White and Thaw grew like a nasty swollen carbuncle. It was a situation the best alienist— practitioner of the new science of “psychiatrism”—might have struggled with, especially in trying to answer the eternal question: What does a woman want?

Specifically, what did the still captivating and barely legal Evelyn want, assuming she had any legitimate options? And how was she to think clearly while being pulled across one line and then another in the tenacious tug-of-war between White and Thaw? More than anything, Evelyn wanted peace of mind and some chance at financial security, since it appeared romantic happiness was a delusion. This meant she needed to believe that Harry was sincere in his apologies for his violent and offensive behavior—and that he in turn had forgiven her sinful “transgressions. ” Knowing she was back in White’s city, Harry wanted desperately to win her away, permanently, apparently willing to endure the fact that she was more Magdalene than Madonna. And if he thought Stanny wanted her back, Harry wanted her all the more. If Harry wanted her, Stanny wanted her away from him—and wanted Harry out of his playground. Each man suspected the other of some more aggressive movement toward his discredit. And pinned and wriggling in the middle was Evelyn, the key to both men’s potential ruin should she decide to go public with her knowledge of either one’s “sexual crimes.”

But she didn’t.

Instead, Evelyn provided Harry with letters White had sent her, hoping that once each side was equally armed, they would cease fighting, sensing the battle a draw. She couldn’t have been more wrong.

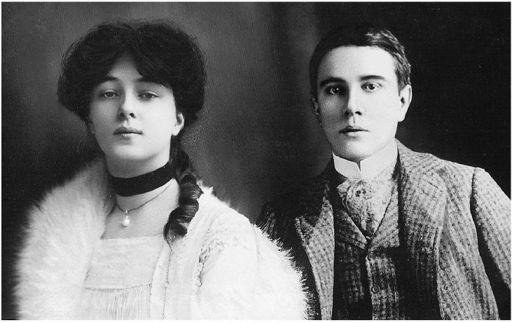

Mr. and Mrs. Harry Thaw, the "happy couple,” in a composite photo, 1905.

CHAPTER TWELVE

The “Mistress of Millions”

“What Is the Fetish of the Fair Young Woman of the Footlights That Makes Western Croesus Lay His Heart and Gold at Her Feet?”